Valery and Ivan have been working in London, Ivan in particular working on not standing out as a Russian who wants his government overthrown. But his writings under the pen name "Taciturn" have attracted attention, and an odd conversation with a man from Smolensk makes Ivan think that he is being ordered by Lenin to leave England, and make his way across the ocean ... to America.

He wouldn't tell Valery. The more he thought about it, the more he thought he could be, must be, wrong, but one night Valery came home and over a dinner of leek soup, veal, and apple tarts told him that Smedlov, the Okhrana chief at the embassy, had inquired if he knew a certain Mr. Ivan Karamazov.

"He asked me this at the end of his weekly briefing for Stoltz, whom he assiduously tells nothing, and he made sure Stoltz heard it. I kept walking into the corridor so Stoltz wouldn't hear my answer."

"Which was?"

"I said of course. We're both 'from' Skotoprigonyevsk, so to speak, and you're infamous. How could I deny it?"

Smedlov had then followed Valery down to his little office at the head of the stairs and sat down on the chair by his desk as if this were his custom after a meeting with His Excellency Stoltz, the two of them tying up lose ends.

"Not so long ago, oh, it's about two years, Karamazov received an exit visa but he never returned," Smedlov had said.

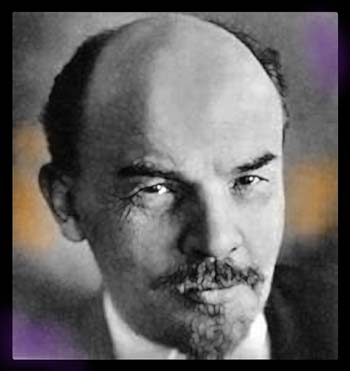

Valery of course knew that the Okhrana had seen him in Berlin with Ivan and Katerina Ivanovna when they visited the Liebknechts, met Ulyanov and then went around with him. Denying that wouldn't do. "Never returned from Berlin, where I last saw him?"

Smedlov had stroked his lantern jaw and nodded agreeably. "Yes, exactly, in Berlin in the company of a Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtsev."

"She's also from Skotoprigonyevsk."

"And what about a Mr. Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov?"

"Yes, we met him there, too. Russians, you know," Valery had added, as if anyone would know how Russians, encountering one another abroad, never let go.

"Who is he? Any idea?"

Valery's demeanor since he'd come to the embassy as the ambassador's aide was almost boyish. He behaved the way he remembered behaving at his father's side. He was good at English, a person you could consult about the meaning of "raining cats and dogs." After Smedlov, he was the least noticeable official on the premises. In fact, he wasn't an official; he'd been hired locally and wasn't on the diplomatic list. Now he thought to himself that if he didn't find an unrevealing way to keep telling the truth, Smedlov would have him trapped.

"He's some kind of political theorist such as you follow here in London, and Ivan Karamazov had become interested in political theory through his readings. Anyway, by pure chance we all called on the old socialist Liebknecht at the same time, and that's how we met and spent a few days on holiday. Sight-seeing, swimming, bicycle riding, things of that sort ... biergartens, what have you."

Smedlov, in a voice tinged with regret, had said, "Ulyanov's been exiled, did you know that? And his brother was executed for plotting to assassinate the czar?"

"...River was as ambivalent as a two-sided knife, cutting sharply in both directions..."

Valery had focused on the news of the exile because it truly was news to him. In fact, he had not seen or heard directly from Ulyanov-soon-to-be-River since Berlin. He only knew, through Ivan, that Katerina Ivanovna was sending money to people at River's instruction, sometimes delivering it herself in Moscow or St. Petersburg. There were carriage rides for which she paid five thousand rubles and equally munificent tips given to a certain waiter in a certain restaurant. The fact that River could make an occasion occur for the discreet transfer of funds in the most natural and open of places apparently pleased her. But she also conveyed the fact that River was ambivalent (probably too soft a word, River was as ambivalent as a two-sided knife, cutting sharply in both directions) about Taciturn. He had told them to go to America. "Sojourning" in London was a breach of discipline. Katerina Ivanovna seemed to share River's ire, or that was the impression Ivan conveyed, though he only talked about her letters, half-written in invisible ink, half-written in real ink (which dealt with her life and feelings independent of these surreptitious activities, feelings of self-mortifying longing which seemed to unsettle and irritate Ivan), never showed them to him. Destroyed them, in fact, each and every one, the scent of burnt paper as he ascended the stairs telling Valery that another one had arrived at the post office box Ivan had taken out as Morris Brawley from Liverpool. (Sometimes they amused themselves building Brawley out -- thirty-nine years old, widowed, a former shipping agent fond of hot cross buns and yellow silk from China who had retired on his wife's income, which she had never allowed him to touch during her lifetime.)

"Afraid I know nothing about Ulyanov or his exile," Valery had told Smedlov. "He was a man we met. Cheery sort." Actually, jeery sort, smug, self-confident and unpleasantly adept at positioning himself behind a woman's skirts, but Valery kept this, along with the image of Katerina Ivanovna's long skirts, to himself.

"You say Karamazov reads a great deal? Does he write as well?"

His Excellency Stoltz, as was his custom on departing the chancellery, stuck his head in Valery's little office to give him last minute instructions. He clearly was surprised to find Smedlov there and to hear this vaguely familiar name again.

"Excuse me, Smedlov. Who is this Ivan Karamazov who interests you so much?"

Smedlov resorted to one of his casual evasions. "One of the hundreds on my list, your Excellency."

"You know him, Valery?" Stoltz asked.

"Sir, we are from the same town. He was a generation ahead of me. His brother was convicted of murdering his father. Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote a book about the affair."

"All nihilism," Smedlov interjected, surprising both Stoltz and Valery with this rare word and confidently associating it with an author and a book you wouldn't call a penny thriller.

"Say that again?" Stoltz had asked.

"Nihilism. What Dostoevsky opposed. Apparently what destroyed, or you would have thought destroyed, this Ivan Karamazov. Dostoevsky skewered him with his own brilliance."

Stoltz knew nothing about the Karamazov affair. Before London, he'd been in Mexico. Before Mexico, Italy. Before Italy, Istanbul. Scandals in Russia escaped him. He was no reader, either, and did not trust Smedlov's sudden eruption of literary insight.

"How exactly did you meet him, then?" Stoltz asked Valery, trying to demonstrate to Smedlov that he also knew a thing or two about ferreting out information.

"A mutual acquaintance, Katerina Ivanovna Ver -- "

Stoltz never liked hearing about women; he hated them and always changed the subject. So he cut Valery off. "Why do you want to know if he writes?" he asked Smedlov.

Smedlov had, thanks to his large face and lantern jaw, an enormous grin that he often used to disingenuously acknowledge someone else's acuity. Now he directed this grin at Stoltz to let Stoltz know that if he thought Smedlov and Valery were cloistered to conspire against him -- which is exactly what Stoltz feared -- he was wrong. No, Smedlov was just fumbling around, looking after Stoltz's interests, which Stoltz had just brilliantly pinpointed all by himself.

"Well, yes, sir, I think you've got it. I mean wouldn't you wonder if a man whom had been written about and likes to read and is well-educated and known for his erratic state of mind and seems to have disappeared, last seen in Berlin in the company of someone we don't like, would have popped up here and become this Taciturn?"

Now Stoltz was not pleased. Taciturn! He became even more annoyed when Smedlov said in his estimation whoever this Russian was, he'd found a home and an audience in the socialists of London -- some of them called Fabians -- and even in the established parties.

"So good at making the English 'titter,' sir. Word that means -- "

"I know what it means!" Stoltz interrupted, although Valery knew Stoltz had no idea what it meant, or why it was that adolescent irony and posturing had such a hold on the English upper classes, turning their anger into disruptive squeaking glee ... but this was what made the lords and ladies happy, tittering among themselves, satirizing one another, belittling things. Often Stoltz would come into the embassy late in the morning and review the cartoons in the newspapers with Valery and ask why they were funny, these immodest sketches of royalty and ministers and Britannia herself. Valery would tell him -- but Stoltz wouldn't believe it -- that this was the way the English thought: ironically. Stoltz hated irony, didn't have time for it. The dinner he'd just attended, for example, what had it been other than this harrumphing and snickering and nasality and grandiloquizing? "Is that a word, Valery? Grandiloquize? Do the English use it?" "It could be a word, sir, but I wouldn't use it myself." "Why not?" "Because they'd know right away you meant them. You'd have pinned the tail on the donkey." "Pinned the tail on the donkey? Now, what the devil does that mean?"

Stoltz had looked Smedlov in the eye and said, "You say he's a Russian? Taciturn is a Russian?"

"Sir, I'm told the way he writes is as plain as the old queen's face, which would make him English, but who would dig and poke and pinch at us if not one of our own? It makes me think we're looking at a Russian."

Stoltz had contemplated this analysis a moment before resorting to his fundamental strategy of command -- never conceding what he was told was good enough to accept, always wanting something better. "Whoever this Taciturn is, I'd like to know. Make it your business."

"Yes, sir. I will, sir," Smedlov had promised.

Stoltz then left and Smedlov, having lost track of his assault on Valery and not wanting to stumble as he regained his footing, had departed, too.

Ivan did not believe that any of this meant that Smedlov suspected Valery remained in contact with him. He had only entered the house in Kensington through the front door once, and there was no Taciturn then. Taciturn took months to create, and he was created through the rear door, which Iris and Jenny found unbecoming. He had his breakfast after Valery, he gave the girls their instructions and funds in the kitchen, and then, as if it were too much trouble to walk through the house to the front door, he left via the back door, crossed the little garden with its koi pond (Iris loved those pretty fish), entered the short tunnel and thence out onto the cobbled mews, as English an Englishman as you please, dressed neither well nor poorly, better than a clerk in shiny britches, less well than a solicitor with a velvet collar on his topcoat, a cracked leather bag containing his papers in his left hand, and an umbrella he'd bought at a secondhand shop in his right.

But even so, an hour after dinner he tapped on Valery's door. Valery was sitting in his armchair reading a great big fat book called Middlemarch by a woman who wrote under a man's name.

"We will have to leave London," he said.

Valery said, "I know. I was going to say that to you tomorrow. Smedlov's too much; he'll ruin us."

"It isn't just Smedlov." He told Valery about the man with the meerschaum pipe. They talked about meerschaum floating on the Black Sea and that face on the pipe bowl. The details diverted and intrigued them more than the weighty conclusions: River and Smedlov were both enemies. Smedlov would get at their bodies. River pursued their will.

"He has no use for what I write," Ivan said. "I can drown in my ink as far as he's concerned."

"Or swim to America through the water," Valery laughed. Then he grew serious. "I'll persuade His Excellency to telegraph St. Petersburg and ask if I could be entered on the lists and work for the Washington embassy. I've looked into it. What they lack is a consul in San Francisco. No one wants to go. I'll say I'll do it."

Ivan had no concept of how far San Francisco was from Washington, much less London, but he did realize it must be closer to Sakhalin where he last knew his brothers to exist than he had ever been since their exile. The idea that he might never see Mitya and Alyosha again was one of a handful of ideas he tried to suppress. They were gone when he regained his health -- his sanity -- in Katerina Ivanovna's house. His whole life was like a story, something he had read, not lived. "America, then."

"America," Valery laughed. "I seem to be reliving my entire life."

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.