"All knowledge, the totality of all questions and all answers is contained in the dog."

-- Franz Kafka

Lǎogǒu is distant now, and it scares me. As stupid as it seems, it really does.

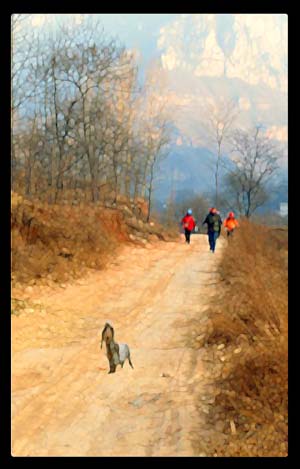

It's strange. I can't call him the dog anymore, any more than I could call my father the man. I invited Lǎogǒu to sleep on my mattress with me. At first, he'd just laugh at my suggestion -- he was afraid of getting fleas, he said. And we -- the girl, Lǎogǒu, and I -- spent nights in his kennel, staring up at the sky as he held forth on the cosmos, making me and the girl learn the Western names of the constellations and the myths behind them. Then it was declinations and hour angles and navigation both with and without sight reduction tables, which we studied until our eyes were bleary and all we could do was nod along. The girl and I are both Geminis, it seems. What was he, I asked once. There's a special zodiac for dogs. We're all born under Sirius, of course! But really, I'm a salty old dog, and probably soon to be a salted one. That's the kind of answer he gives to the simplest question.

At least you find yourself amusing, I tell him, because it's lost on the rest of us mere mortals.

As of late, he's relented, and he curls up beside my belly; there isn't much else left of me to curl up against. But I can still feel the cold rising up all the way through the quilts, and I worry if he suffers for it. Everything is too broken down now, including me, and I'm in no position to carry any burden. I'm scarcely in a position to carry a book. I keep trying to make a joke of this, keep trying to see how losing a friend makes things any better, but I can't.

Yes, he's old. I know it, and how could I forget? He makes a joke of it every time he coughs something up or every time the doctor comes around. His humor doesn't make things much easier for us, but at least it's better than the professionally concerned looks of the white-coated expert.

The father of the beautiful one has come around too sometimes, always with the doctor, and looking even more hangdog than Lǎogǒu could in a thousand years, but never before his son was long since passed out in the chicken coop on beer and báijiǔ. They all sat in the kennel talking in the soft tones of tired old men, smoking Shuangxis until the sky was pitch black and the cherries of their cigarettes looked like red dwarfs mere degrees above the horizon, the points of light twinkling whenever one of them spoke. The midget joined them sometimes, her magpie squawking piecing the summertime blanket of humid air and mosquitoes. The little girl -- the midget's midget -- and I were never invited, and neither of us felt much inclined to barge through the gates even if we could.

The meetings of the Hunan Kennel Club stopped as suddenly as they began, as though some matter of no small import had been resolved.

* * *

"Every problem has a gift for you in its hands."

-- Richard Bach, writer

I've got a headache, and it's the worst I've had since my son first looked in a mirror. I think . . . I think . . . I think it's all the thinking. The dog makes sense -- too much sense, as a matter of fact -- and I wish I knew any reason on earth to disagree with him, but I can't. Between him and the doctor, everything has been worked out already. All I need to do is go along with it. And they are treating this as though it's pure science. Perhaps it's genius -- this directness of thinking -- this understanding of when things are really as simple as they seem.

It won't be your fault. You won't make him do anything. Whatever happens will be his decision. I wish I could believe that. I wish I could believe that my fool of a son was capable of thinking for himself, but I know better. This is the problem with rational creatures: they don't realize just how rare their powers of reasoning are. My boy couldn't win a debate with a lamppost. How does he stand any chance against these two?

Still, I know they're right, in their ends if not their means, and I feel even worse for my son's wife and daughter than I do for myself. To be rid of him would be a blessing for them. And what about the hooker? they ask me. The brainy bunch are good with questions I can't easily answer. Couldn't she use a hand as well? Well, I suppose she could, and she isn't a bad girl, not really.

I know all about it. I know how she lost her legs. Her father never said a word, of course, but news gets around. There aren't many secrets in this world, just things we won't admit in public.

Now you think I'm a gossip, do you?! Well, don't get all high and mighty with this old man. I'll have none of it! I know what you people talk about in your free time, or at least I can make a pretty good guess. And I never carried tales, just listened to what was told to me. There's no fault in being a sympathetic ear.

What about loyalty? You ask. Fool or not, he's your flesh and blood, and family is the be-all and end-all, don't you know? Well, there's a hole in my heart where love for my son should be, and I can't take any more disappointment. You damned hypocrites can't say anything worse about me than I've already said about myself.

I have paid off debts, soothed weeping mothers, and talked fathers -- my friends at that -- down from murderous rages. I have stood between my son and husbands armed with knives and righteous fury. Now, I stand aside. I will no longer protect this boy -- this eternal child -- from himself.

You might think that I'm not really making up my own mind and that others are doing all my thinking for me. Maybe that's the case, but I've prayed at every temple in three provinces, climbed Mount Heng every year wearing black robes and with a black bandanna tied around my head in the manner of a good pilgrim, and bought and burned enough incense to pay for a perfumer's mansion. What has it gotten me? A son that is now not only a fool, but a blessed one.

If the gods won't help me, maybe the dogs will!

* * *

"It is the friends you can call up at 4 a.m. that matter."

-- Marlene Dietrich

I hear him pacing, muttering in German, and I don't think it's from pain.

Eine hundehütte . . . die Hölle. I have no idea of what it means, but he keeps saying it. He always laughs when he does -- a low, bitter growl really -- pulling his lips back into a tortured expression that isn't quite a snarl but isn't far from it. It's the same thing he says when I ask where he was born.

Yesterday, he asked if I could use a new arm? "Would you like to be a little less incomplete?" he asked, looking as sober as a monk.

How do I answer that?

If I had another arm, I'd not be as helpless as I now am; I'd have a job where lying down in the middle of the day wasn't advisable, much less compulsory; I'd be able to buy a wheelchair and be able to use it for something other than going in circles. And I could use an arm too. I know a surgeon, a good one, so it seems as though your favorite legless streetwalker has some guānxì herself, never matter how she got it. (Some of these doctors have the most curious proclivities.) But it isn't quite enough, not enough to get me a spare arm. Blood type doesn't matter now. The Japanese -- firm believers in its power over destiny, personality, and social compatibility -- figured out how to change a person from +A to -O to +B to -AB and back again in a matter of minutes, and they do, most often as a matter of vanity. And tissue is now all but universally compatible, but the arms trade is big business, and as expensive as a real arm is, an LG Lifelimb is far worse, and a Huawei 8-hand-8 is not much better, and even more complicated to install.

Lǎogǒu doesn't wait for my reply. "Tell the old man's wife to bring the wine to the kitchen as soon as she gets here, and when you see the old man, remind him that the doctor will be needed by no later than four."

After that, he turns and starts to limp his way towards the midget's kitchen. He angles his head back.

"Do not forget to mention the doctor," he snaps.

"Where are you going, Lǎogǒu?" I ask.

"From whence I have come I shall soon return." He pauses as he says it, just long enough to give me a look that I wouldn't dare follow.

* * *

"If the headache preceded the intoxication, alcoholism would be a virtue."

-- Samuel Butler, novelist

Bah!! So the old man thinks he can cut me out of the family? That some small slip of paper -- some lawyer's scratchings -- will make me any less his son, any less his responsibility? What sort of man divorces his own son?

He wants to be free of me?! I should be free of him, him and his thin and watery blood! Some great revolutionary he was. What a brave man -- so cowardly that he wouldn't even tell me -- the rightful holder of his pathetic little name -- of his plan to my face. So he sends out my long-suffering mother with a case of Red Star báijiü and that note.

Son, please sign this. I will come to collect it soon. And forgive me. I only want for us to all be free of our unnecessary attachments.

Me, an unnecessary attachment?! I almost thought to return the báijiü when I read that, but I'm not a martyr, and I'll drink every last drop before the cheap bastard comes to try to take it back. He owes me more than this, but I think it's all I'll get.

I should rid of him of his piddling little life. What use does the old weakling have for that? I know where he keeps his rusting blade. I bet all his blades are rusted through and through. Ha-ha!

Bam! One less old half-wit!

I won't go that far, though. It's what everyone expects anyway, so I'll not lay a hand on him or the old hag -- old mommy dearest -- a beauty in her own right before he destroyed her. No, I'll prove them wrong if it's the last thing I do.

I'll rise up out of this pigsty and be rid of all these parasites. The useless wife, the trembling daughter, the legless mistress, even that damned dog -- I'll be done with all of them. I'll move on to greatness!

They'll all see!

I'm not just a pretty face, although that I will always be, no doubt. I'm a king, a king in search of a kingdom. Hear the trumpets sound for me. Hearken to the call of damsels as they sing my praises (but not as well as I could).

I'm the king of beauty. I'm the king of style. I'm the king of music. With a little money, I'll go far in this world even now, and I know just how to get it, because I'm a king, a king of cunning. I'm what every woman wants, and what every man wants to be. What am I? I see it writ large in the sky:

I'm the karaoke king!

* * *

"As it takes two to make a quarrel, so it takes two to make a disease, the microbe and its host."

-- Charles V. Chapin, public health pioneer

The girl was fine, really. I don't know why he kept bringing her to me. She wasn't sick, just small and scared. Frankly, I don't think he cared much about her. It was a pity, too. She needed some protection and a little love. I suppose she got those, though not from the most typical of sources. Things are better for her now. I'm grateful for that. I didn't go into this business to watch people suffer.

Him?! What do you want me to tell you about the subject? Well, this is purely my professional opinion, so I mean absolutely nothing personal when I make the following statements. Medically, he suffered from . . . how do I say this? Development of Un- Myelinated Bilateral Autonomous System Substantially Slowed (DUMBASSS) disorder is, I believe, the current Western term. It was also called CNSIQI -- CNS Intact, Quantity Insufficient -- in Britain when I last went to a conference there, but that was many, many years ago. Beyond that, there was nothing wrong with him, except for the fact that he was missing a limb. He did appear to suffer from tremors, but those were at their worst on his sober days, which were so infrequent as to be statistically (and practically) negligible.

And then there was the syphilis. How the details escape a man!

He never would let me properly treat that for him, which is just as well. Those who can't take antibiotics regularly shouldn't take them at all: It's a simple matter of preventing the development of drug-resistant pathogens. Never matter. I suppose the numbness and trembling of the extremities shouldn't be major issues any more, and as for damage to his higher cognitive functions -- the only thing any competent nano-surgeon couldn't have repaired in the better part of an hour -- well, seriously . . .

As for the idea about the dog, I don't know how or where exactly he got it. I never really told him as much, but ideas that no sensible man would seriously consider for a solid minute take root in the minds of fools and charlatans like an apple seed planted in the loamiest soil. The subject is profoundly demented, so much so that he even thinks he can keep a tune, which is a sure sign of either a decaying mind or a developing deafness.

Once you've been a healer long enough, you realize that people -- even the supposedly sane ones -- hear what they want to hear, if they can hear at all. That's the very trait that makes about half of them sick in the first place. That was probably his biggest problem.

That and neurosyphilis.

* * *

"A good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan executed next week."

-- George S. Patton

"You do realize that once we start this, we won't be able to stop, and there's no guarantee that it will work at all."

"What choice to I have, Doc? I'm running out of time, and quite frankly, I'm just not content to sit here wallowing in self-pity."

"How bad is the pain?"

"I feel it, Doc, and I'm starting to feel a little more of it every day."

Lǎogǒu was never one to complain. Even when we were captured by the post-default PAHF (Privatized American Hyperinflation Force), he never yelped. And they were brutal: famous for hammering decimeter thick rolls of hundred dollar bills -- nearly enough money to buy a tube of hemorrhoid cream -- into every one of their detainees' orifices. I can only imagine what he is feeling now.

"I wish I had better news, Lǎogǒu. I really do, but it's already spread too far. I could order replacement organs . . . "

"And the money for them would come from where? The Talking Dog Benevolent Fund?" He's getting testy.

"Do you think the woman will go along with it?"

"Which one?"

"Well," I realize that there are indeed four women who would be potentially involved in this. "All of them."

"The wife . . . with relish." He offers a dark smile as he says it. "The old woman . . . probably." Another pause. "Don't tell the prostitute."

"But this is for her more than you. There are easier exits for you, and less humiliating."

"All the more reason to keep her in the dark." He says it so firmly, with such total conviction, that I don't argue.

"And the girl? This is for her as well."

"I'll deal with her. She doesn't need to see any of what transpires."

"So that's everything? There is nothing else to discuss?" I put down my cigarette as I say it. Absorbing the finality of it all takes a moment. "What about the father?"

"You know, Doc, those things will kill you." He points his paw at my cigarette.

"You too," I nod back at his, still clinched between his teeth.

"You want to live forever?" He laughs, his low ha-ha-woof reverberating in the twilight.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.