This article originated as a talk given at the Creative Writing Forum sponsored by Renmin University Press, Beijing, China, July 13-15, 2016.

Kinds of writers

I'm guessing that everyone reading this is a writer to some degree -- that we are all interested in expressing ourselves well in words, and we all aspire to be better writers.

Some may be established writers. They have published a number of works, their names are familiar to readers, but they may also realize that there are still things they can learn about writing. Anyone who has experienced the satisfaction of having a poem or story published knows that it is only a temporary satisfaction -- there's always the challenge of the next poem or story that's waiting to be written. A writer is always beginning again.

Others may truly be beginning writers, people who are curious about what this business of being a writer is all about and are thinking they might give it a try. But most probably fall into the wide category between those two groups, the category which I call "aspiring writers." You have written a few things, but you aspire to write more and to learn to be better at it. You're not well-known as a writer, except maybe to your close friends, but you gain personal satisfaction from the process of expressing ideas that are important to you. Maybe you have published some of your work, won a few prizes, or made a bit of money from your writing. But you have another job by which you make your living.

With all this in mind, I titled this article "Being a Writer," since most of its readers will already be writers at heart and the "becoming" stage has been accomplished. I think it will be most profitable, and practical, for me to address the challenges of the day to day aspects of being a writer, drawing on my own experience. I myself fall into that big middle category between beginning and established writer: I've been a teacher of English literature and composition for more than forty years in the U.S., Canada, and China, but I have also been a writer, in one way or another, since childhood. So I know what it is to be a published writer, and to sometimes even be paid for my writing, but I also still have aspirations -- ideas for more things I want to write that will be better than the ones I've done.

Stages on the way to being a writer

A good way to start a discussion of the topic of writing might be to think about how a person becomes interested in writing, and what it is that is fundamentally interesting about writing. You probably share some of my experiences. At the very beginning comes reading. If you like to write, you love to read, and you probably learned to love it early on. That's usually how writers begin, as children who loved being read to, and who then gobbled up books on their own as soon as they learned how to read. So I'm sure all of you still remember the absolute magic of those childhood stories, how you felt as if you were really a part of those simple adventures that featured cute animals and children just like yourself.

Since children love to imitate, you might have folded up a piece of paper to look like a little book and drawn pictures and written little stories about things that interested you. I did this, and my children did it too. (They didn't become writers, but they still love to read.) When your teacher in primary or high school assigned a story or poem to be written, you probably did well because you'd already done some writing on your own.

It was at this stage, when I was about eleven, that it first occurred to me that being a writer was something I might want to do. But when I said this out loud, when the teacher asked us what we wanted to be when we grew up, some of my classmates looked at me in a funny way ... I never said much about it again, and I changed my ambition to "teacher." But it was always in the back of my mind as I read stories and novels, and secretly wrote a few poems.

Most schools and universities have student publications, and this is the place where many would-be writers are first published. I submitted a long poem to my college's literary magazine at the beginning of my third year of university, and having it accepted was very exciting. Even more overwhelming was the reaction of several of my professors. They were actually impressed with my writing and one offered to help me submit poems to real literary magazines. By the end of the year I had a poem accepted by a magazine in St. Louis, Missouri and I felt that I might actually have a chance at becoming a writer some day.

From then on, while finishing my undergraduate degree, earning an M.A., and then beginning a university teaching career, I thought of myself as a poet as well as a student or teacher. I "got down to business," although in a somewhat sporadic way, submitting poems to journals and contests. I also began to write short fiction and over the years moved from earning ten dollars for a poem to one hundred dollars from a contest, and a few times, eight hundred to a thousand dollars for a short story. Teaching was my job and I liked it, and being a wife and mother became the central part of my life as the years passed, but I still found satisfaction and pleasure in writing -- when I was able to find time for it.

And that is what is commonly called "The Crunch." Decisions have to be made and priorities considered at this stage in a writing career -- or any career. If I had been determined to become an Established Writer, I would have had to go in a different direction at that point. I would have needed a literary agent, and I should have become more involved in my local and national writers' organizations in Canada.

I was contacted by a literary agent in New York City when I had a short story published in Redbook magazine. He was interested in my work and asked to see some other things I'd written. I sent him the draft of a novel I was working on, and he soon returned it, saying there were already too many novels with academic settings, but he asked if I would be interested in writing fiction for young adults. I wasn't -- it had never crossed my mind, and I wasn't even sure what sort of writing it was, so that was that. I was too busy teaching and raising two children to pursue the idea of an agent.

Likewise, while I did get involved in my local Writers' Guild, going to events now and then, I didn't really have time to travel to various parts of the province or country to participate further and network with other writers. Looking back now, I realize that if I'd been determined to raise my profile as a writer, I should have sought out another possible agent and become more involved with the writing world. But my family was my priority at that time, and my teaching responsibilities came next. I devoted what time was left over to writing, which also gave me satisfaction, and I'm happy with how it all worked out -- I found the right balance for me. However, I pass these realizations on to you for your consideration. We all have to decide what will work best for us.

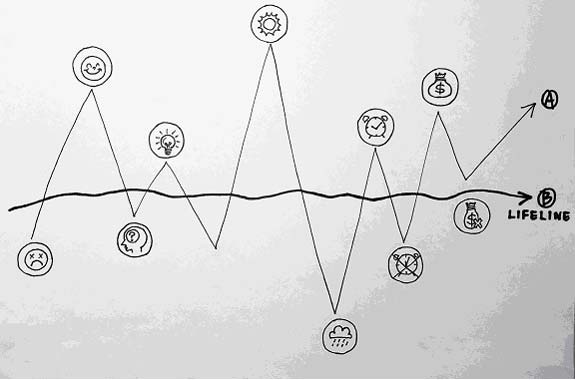

A Picture of Being a Writer

Being a writer has its ups and downs, to say the least. (See Line A: Ups -- acceptances, praise, prizes, self-confidence, publication, writing-related work, time to write. Downs -- rejections, negative criticism, lack of confidence, unrewarding work, no time.) Added to these rapid fluctuations of fortune, you work alone. You can either be your best colleague or your worst enemy, depending on your attitude toward the ups and down. The best way to keep your work on an even keel is to fight discouragement and keep going. The key to helping you do this is to make an effort to get down to writing on a regular basis. This is your stabilizing lifeline (see Line B): the routine of writing something on a regular basis -- every day, a few times a week -- that will keep your work alive and moving forward.

The Lifeline: Materials and Methods

Materials: The Place (for your work)

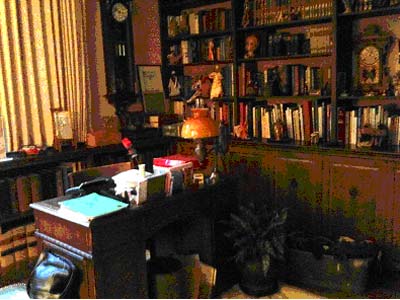

"The study of the famous German writer Thomas Mann"

This shows the ideal writer's workplace, a dedicated room filled with inspirational books, pictures and mementos, a place to spend several hours a day, with a wife like Mrs. Mann elsewhere in the house keeping out intruders. But few of us can hope to have a workplace like this -- we make do with what space we can find. However, I've discovered that more important than a good workplace is a good place to keep your work, the actual writing you are working on at the moment, and that's an entirely different thing.

It's very helpful to keep your work somewhere in sight. At home in Canada, my computer was in a spare bedroom, but I had another small desk in the living room where I always kept a folder of my current work. Here in Beijing we have a very small one-bedroom apartment, and I keep the folder on a table in the living room which also serves as my desk. Having my work out in the open keeps me from ignoring or forgetting about it -- it's always in sight, not hidden away in a drawer in another room. That way it's easy to pick up and work on if I think of something I want to add to it. It's a visible part of my life, something that I'm responsible for tending on a regular basis, a little like a child, or a pet, or a plant -- something I can't easily ignore or dispose of. It's always there, reminding me of its existence.

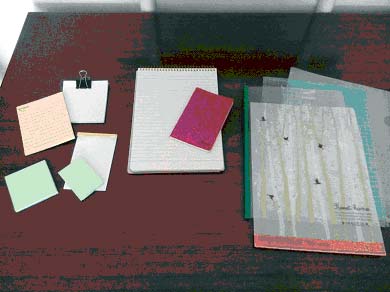

Materials: The Pile

I call this folder "the pile". The photo shows the pile containing the notes for this article, sitting on my desk in the living room, staring at me, reminding me to get on with it.

Materials: The Accessories

What are these accessories made up of? Here you see the various writing materials that I always keep on hand. First, there's a plastic folder which holds all the notes and drafts I accumulate as I begin to work on something. It looks like kind of a mess as it fills up, but I like that. It gives me the sense that I have lots of possibilities to work with. The other necessary accessories are various sizes of notepads that I keep handy on my desk (but I carry the pink one with me all the time), and my favorite type of writing notebook, a rectangular spiral-bound notebook where I expand the ideas recorded on the notes. I'll say more about how I do this when I talk about "Method" in a minute.

Materials: The Spark (The Initial Idea)

No photo -- this is something you can't see, but it's really the most important element in the whole writing process. It's the spark, the initial idea, the point at which your work begins. Who knows where these sparks come from, but you know a good one when it arrives, and if you hang onto the interest and excitement it generates in you, these feelings will see you through to the completion of the work. (Bad ideas usually fizzle away.) For example, the spark for this article was the pile of work that was sitting on my desk at the time -- a story that I was finishing up. It gave me the inspiration for a very practical essay on my own writing process rather than a more general type of "pep-talk" for writers.

As for the initial ideas for my more creative writing, the stories and poems, those sparks have been made up of a sudden fascination with some topic and a real need to express my feelings and ideas about it as clearly as possible. For example, when my family and I moved from Canada to Macao years ago, I read a lot about the experiences of British and American women who had lived there in the 19th century during the days of the tea and opium trade. It was fascinating to think they had walked on those same hills and streets that I was exploring, and that they'd had many of the same problems I was having, adjusting to a mixed Asian and Western culture in a semi-tropical environment. I suddenly wanted to write a poem that summed up the experiences of these women I identified with, who had lived in this same strange and exotic place more than one hundred years before. The whole idea stuck with me and pestered at me until I got the poem written. It helps to be a little bit possessed by your topic -- it keeps you going and it assures you that it's a good topic. You feel uneasy until you get it just right -- then you feel very, very good.

Method: The steps I follow (more or less), using the above materials, once an interesting idea has arrived.

- My preference (yours may be different) is writing by hand first, until I have a few substantial pages, and then moving to the computer. Some people are more at home with typing their work right away, but I'm too used to thinking on paper. I find it difficult to type my ideas straight out of my head because, to me, bad writing looks really discouraging neatly typed on a screen. But it doesn't look so bad scribbled on paper. So I do a lot of jotting and scribbling and organizing before I type.

- First, I collect short notes on an idea, wherever, whenever. I try to pin these thoughts down on small pieces of paper either sitting at a desk, or settled in a comfortable chair, or when I'm out somewhere in the middle of something that has nothing to do with the topic, and an idea suddenly pops into my head -- while shopping, cooking, cleaning, riding my bike. I stop and make a note. It's nice how this happens when your mind is relaxed. All sorts of things can start bubbling up. That's why I always have a small notepad or notebook close at hand.

- From time to time I sit down more seriously and go through these short notes, clarifying, consolidating, expanding, and discarding the ones that now seem stupid or off-track. To me, this work qualifies as writing and it's a good way to warm up to the actual writing of sentences, paragraphs, and pages. You will surprise yourself sometimes by accomplishing far more than you meant to when you just sat down for fifteen minutes -- you'll look up and an hour has gone by, and you have done some writing.

- Keep this collection of notes and beginnings in a folder and keep feeding and tending it from time to time (like a pet).

- Then you can move on to expanding these notes on a half page or a page of paper, and then start writing the actual manuscript in a spiral notebook. I find this type of notebook especially useful because you can tear out the bad pages and leave the good ones still nicely bound together and organized. (I go through a lot of these notebooks -- luckily they sell them at the local grocery store.)

- Then, once I have something substantial in the notebook -- a whole poem, several pages of a story -- I type it into the computer where I can then see clearly what I've done. Then the rewriting and revising begins, made easy by the wonderful features of word processing.

I find that this step-by-step process takes a lot of the pain out of writing. It allows you to sneak up on a project, doing small, easy bits of writing at any time of the day. It also allows you to work part of the time away from a desk, collecting notes and ideas wherever you are. Then once you have a folder stuffed with good ideas, sitting at your desk for an hour or two and working on improving them becomes a pleasure. The worst thing you can do is to force yourself to sit in front of a blank piece of paper or a computer screen with nothing to work from, without one helpful idea in your head.

Dealing with Writer's Doubts

So it helps to have a method and some useful techniques. But as with most important undertakings, it can't always be easy. Inevitably, there will be those doubts and fears that all writers have to face at one time or another.

For example, "Do I have something worthwhile to say?" At some point you might begin to wonder if writing is a territory reserved for people who have more ability than you, and if you just might not be smart enough, or educated enough, or experienced enough in life to succeed at it -- basically, you worry that you don't have anything worthwhile to say. You will definitely feel this way when work you have submitted has been rejected. The best way to avoid this feeling is to put yourself in the position of being an expert: write about something you know about absolutely, and something you feel must be written about. It can be a place, a type of person, a dilemma ... many things. Whatever it is, if you've had personal experience with it, you'll discover you have deep reserves of feeling and detail to call upon that will make your writing interesting and effective. I feel that happening to me when I write about being a foreigner in China, or about places I've known all my life.

Another question would-be writers ask themselves is, "If I did try my hand at writing, would anyone publish my work?" True, it's hard to publish in print these days, with books, bookstores, magazines, and newspapers disappearing before our eyes. You can't just send off a story to New York or London and wait to see if they'll accept it, and maybe even pay you for it. But there are all sorts of new opportunities on the internet that you all know more about than I do -- blogs and various sites that publish stories and poems -- and quite a few writers have gained readers through internet publishing. (I've had two stories published on a U.S. site, Piker Press.) There are also creative possibilities in self-publishing -- places like Amazon and others, and there's also your neighborhood photocopy shop. You can have your own books printed up and then distribute them to family and friends. I've done that with two volumes of travel diaries written by my grandmother, and a long short story of my own.

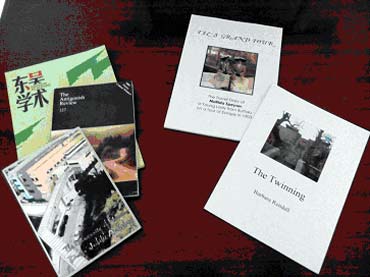

"Into Print: Journals, anthologies, self-published works"

Finally, there's the eternal problem of time. Many people say, "I'd love to try writing, but where can I find the time?" Actually, time is a weirdly elastic thing, and some people are better at managing it than others. Busy people are the best at it -- they know how to fit things in, from experience. (Thus the wise saying, "If you want to get something done, ask a busy person.") Such people can find extra time in the busiest schedule. For example, there's a friend of mine in Canada, Gail. She is a busy professor, wife, and mother who decided she wanted to try writing a mystery novel. She researched the topic, came up with a female heroine and a hometown setting (Regina, Saskatchewan, which she knows really well), and she carved out pieces of time in which to write -- during lunch hours, or late at night on her back porch, wrapped in a coat, by the light of one dim bulb, with no one around to bother her. She said she'd decided "that big chunk of time with my name on it was never going to arrive," so she snatched bits of time at odd hours. She wrote one book, it was well-received, and as her children grew up and she gained more time, she wrote about ten more in the series. And she's still writing.

Another friend, a professor who is an authority on the Irish writer Oscar Wilde, when she was newly widowed and had two children to raise alone, had a publisher offer her ten thousand pounds to write a biographical novel on Wilde in six months. She had all the materials on hand from a previous critical book she'd written on Wilde; she just had to put it into novel form. At that point in her life she really needed the money, so she forced herself to write 500 words a day, no matter what, even on Christmas Day -- and she finished it on schedule. When she looks back now, she doesn't know how she did it.

Yet another writer friend has the theory that many writers have done their best work writing in a closet under a staircase with five hungry children crying outside. That is, sometimes pressure of circumstance is more helpful to a writer than a beautiful study and hours of quiet; a snatched half-hour can be more productive than an aimless afternoon. It all goes back to that idea of sneaking up on a writing task and doing it in bits rather than waiting for a whole free day. A portion of useful time is always within our grasp, here and there. It's a good idea to seize it and make something of it.

A Few Last Random/Quirky Suggestions That May Help to Keep You Going

Vary your workplace When we think of writing, we think of the desk and computer, or a spacious table if we need to spread things out. But sometimes a more comfortable and casual arrangement can be less intimidating and very helpful. If I'm trying to get started on something or am working on a knotty problem, I go and sit in a comfortable chair with just a small pad for half an hour, just before I have to go and do something else. When I relax and commit myself to only a small amount of time, I usually get good results, accomplishing more than I expected (and forgetting the other thing I was going to do!). Doing a little work in a café can work the same way.

The pad you carry with you I mentioned the usefulness of small pads and notebooks before. This is just a reminder to always carry one with you, along with a pen that works! It's only common sense, and you all probably do it (or you use an electronic device), but it's really crucial. If you get a good idea when you're on the go, you always think you'll remember it, since it's so good. But half the time you forget, and that's really frustrating. Always write it down!

One kind of writing can lead to another Be open to the idea that the story you're working on may be better as a novel, or that bit of family history you're putting together may become a poem; an idea for a novel might be turned into an article. Try new writing ventures: I wrote a newspaper column for three years in Canada, and I discovered all sorts of new things to write about; or keep a diary -- it may turn out to be a good source of writing ideas.

Stopping and starting again When you stop writing for the day, be sure you have an idea of where you are going to start next time. It makes it much easier to begin writing again. And before you finish a writing project, start thinking about the next one. The British writer Virginia Woolf always liked to have a vague picture in her mind of her next novel. She described it as resembling "a fin far out at sea" -- like an unknown sea creature far in the distance, mysterious yet intriguing. Start nurturing it subconsciously, gathering ideas. Don't let there be a gap in your lifeline.

Be curious about the writers you admire, past or present Read about the lives of writers you admire. It can be very reassuring to learn how often they were disappointed with their work and thought what we now regard as a masterpiece was a failure. Discovering that they, too, had to fight to find time to work can make you feel better about your own struggles.

On your travels you can visit the homes of famous writers and be surprised by how simply some of them lived, how very basic their work spaces were. At American author Louisa May Alcott's home in Concord, Massachusetts you can see the desk her father made for her, a board nailed in the space between two windows.

You can also look at the manuscripts of writers you admire in large libraries or on the internet. This can be very encouraging because their scribbles and crossings-out are so familiar-looking -- their work looks a lot like ours.

In conclusion ...

And so, what is it I've been trying to say about being a writer -- be me? No, but I hope it's been helpful to hear about some of the things I've learned over many years of writing. We all know there's no simple formula for being a good writer -- you have to find your own way with a combination of practical, everyday techniques and routines plus long-term aspirations and growth. Maybe the most important conclusion we can reach is that a person who works at writing as regularly as possible, and who gains pleasure and satisfaction from doing this work is a Genuine Writer. This is a category beyond beginning, or aspiring, or even established writer. A GENUINE WRITER IS THE REAL THING.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.