There's a payment owed for what you have received...

~~~

Annegret Gumpert looked at her reassuringly cluttered desk, piled high with books and folders containing things she actually wanted to do. Creative people needed clutter. This sight made her happy even though her eyelids were getting heavy, and the laser printer next to her desk continued to exude a somewhat frightening stench of burnt plastic and ozone.

Her working day in the library of the chancery office of Fredburg, one of the last few before she retired, would last longer today. Her unworldly partner was scheduled to show up once it got dark, which, in November, fortunately would be around four thirty in the late afternoon.

Annegret wiped the sweat off her plumpish, not so gracefully aging face. She tried to close her tired eyes quickly enough. Didn't succeed. The flow of sweat ran down her forehead and nose and then, of course, straight into her eyes, temporarily blinding her. Something about the contours of her face facilitated such mishaps.

The rest of her was actually fit and almost trim due to all the running around she did despite swollen feet and occasionally stiff knees. Library work in this company library wasn't a sedentary activity. Her gray hair hadn't come from pushing book carts; it had come from struggles against stupidity. In a bureaucracy, incompetence tended to rise up to the top and stay there.

She never left work with her step counter showing fewer than fifteen thousand steps per day. Forty years of keeping the users satisfied in a special library with offices and stack rooms spread out over five stories in two separate buildings had kept her active and healthy, or healthy enough.

Shrewd from the very beginning, she had made necessary, pragmatic choices during these forty-some years.

She had learned to wear loose, tunic-length, patterned blouses, roomy jeans and sensible, sturdy, flat shoes at work.

Her work clothes weren't perhaps particularly professional, but they made it possible for her to climb ladders and navigate steep staircases. None of the higher-ups were willing to pay for a new building for the library, and so she had to make use of every space she could find in the old buildings. She needed room to store the library's media units, the new correct word for print material, films, photos, and computer storage devices.

The chancery office building itself was constructed from 1903 to 1906 for what was then considered a scandalous sum of money. Walking from the streetcar stop each day, Annegret liked to gaze at that red, four-story, sandstone monster with genuine turrets at each end. The chancery office building filled up an entire city block. While she didn't expect to see dragons flying around the turrets, demons and angels weren't all that unrealistic.

Annegret had long since lost any capacity for being surprised.

The architect of the building had designed and supervised the construction of a solid structure supposed to last for centuries. Modern passers-by thought it was a castle. People who worked there had other ideas. Their work experiences influenced what they felt about the architecture.

Annegret liked her library workspace still located at one end of a stack room on the ground floor of the old building. She would miss this place, though not all of her working conditions. The one-meter-thick, stone walls kept her work area fairly cool in the summer, and the radiators with a direct connection to hell kept it broiling hot in the winter. Her computers were old and loud, but fairly reliable.

Six red sandstone columns, each one meter in diameter and sporting two-centimeter wide, green bands painted at the top and bottom, supported the floor above her. They took up valuable space in the stack room and limited the meters of shelf space she had available for books in this room, but she liked them anyway.

Obviously, the architect had never intended for this room to be a library. However, since he more or less had gotten run out of town for building such an expensive structure, today no one knew what the original purpose of most of the rooms was.

Annegret was alone at the moment and could therefore open a window, which would result in some slight air movement, not to mention the luxurious privilege of additional oxygen in the room. It wasn't that cold outside and was stifling indoors. Unfortunately, most of her users hated air movement for some reason, claiming that the hint of a breeze would give them pneumonia.

She stood up and shuffled over to the window. Her window faced the indoor courtyard that was also the backyard of the archbishop's residence in the Pfaffengasse.

Annegret had a pleasant view of trees, bushes, and grass. Many of the employees in the chancery office had their offices on the other three sides of the building which faced loud, exhaust-spewing traffic.

Her feet were swelling up again, puffy feet to match her puffy face. She hated to admit that Herr Tristan, the rambunctious young apprentice from IT support, might be right when he told her it wasn't healthy for her to sit hunched over her keyboard for hours at a time. Unfortunately, the books and other media didn't catalog themselves. And she wouldn't be doing this forever.

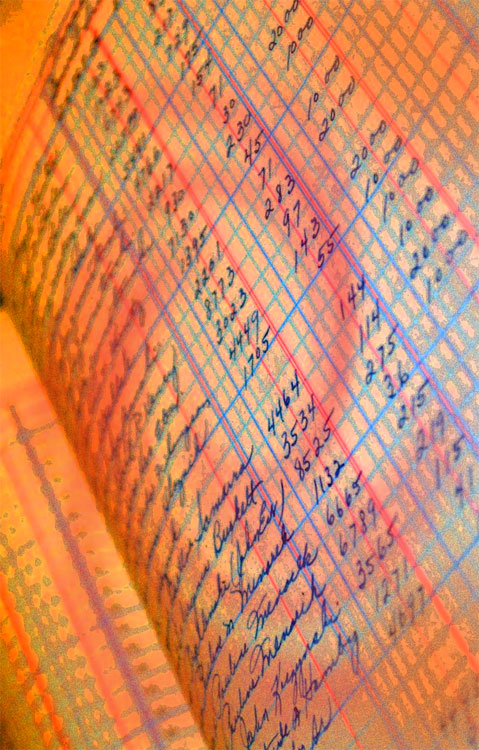

At the moment, today's e-mail informed her that the idiot bookkeeping department had new demands that would take up too much of her time. They were returning to the old system, and she had to find all the original paper invoices she had long since scanned into the program. Annegret clenched her aching teeth, and dug her fingernails into her palms to keep from screaming.

Instead, she walked to the back of the stack room where she had set up a small reading area for the users with four white, metal tables and six cheap, black, metal chairs. Surrounding the tables were the equally cheap, white compartments for the newest editions of newspapers and magazines. They were ugly but effectively hid this reading area.

Since the library subscribed to local and national newspapers, this reading area was a popular meeting place and the location of the office grapevine for employees. The chairs were seldom empty.

Annegret benefited from hearing all the anecdotes, generally about the psychopath higher-ups who kept everyone from working effectively. Knowledge was indeed power, and Annegret had never had any inhibitions about using the information she gathered here.

But for now she needed to deal with the newest bookkeeping nonsense. As Annegret walked back to her cluttered desk, Silke, her student help and successor in the library, came through the door pushing an empty metal book cart. As usual Silke's long, red hair sticking out in all directions and her slim, slight stature made her look twenty rather than thirty.

In over forty years in this organization, Annegret had had her successes and failures. It was a relief to have one final success before she left, getting Silke into her position in the library. Silke Wissler had been her industrious and friendly student help for the past six years.

Like so many youngsters, it had taken Silke a while to discover what she wanted to do in life. Fortunately, now she was willing and able to take over for Annegret.

In Annegret's opinion, Silke had wasted valuable years accumulating one bachelor's degree after another. Once she started part-time work in the library, though, Silke discovered her passion for the profession.

Annegret had enjoyed watching Silke develop from an insecure, anxious student into a compassionate, capable librarian. With a little pressure on Annegret's part, Silke had enrolled in an online degree program and gotten her masters in library science, just in time for Annegret to retire.

"How are your feet doing?" Silke asked.

Annegret sighed. Silke had so many good qualities. It was a slight nuisance that she was overly concerned about Annegret's health. For various reasons, Annegret wasn't.

"Nothing to worry about," Annegret said.

"But you will go have a complete check-up after you retire, when you have time," Silke said. "Then you will have no excuse."

"Yeah, yeah," Annegret said. "I'm fine, just annoyed at the bookkeeping department."

"Why?" Silke asked. "We both finally got the new program to work and have been paying the library's bills electronically for two weeks now. There haven't been any complaints, and the bookstores have gotten their money."

Annegret laughed out loud. "You haven't worked in this place long enough," she said. "We spent over six months struggling with the program. I don't know how many hours we spent trying to work around flaws. Today, I got the notice that they are abandoning the program and everyone has to process bills in paper form and hand them in at the mailroom, just like we used to do."

"Why?" Silke asked.

"One of the IT people suddenly discovered that the program violates the newest European Union regulations for data protection," Annegret said. "It would be illegal to use it."

"It's not IT department's fault. Herr Hollenbeck, that idiot head of the finance department until he got arrested for theft and was fired, bought the program for the chancery office and insisted that we use it. The IT people were never consulted about the purchase. I always had my suspicions about the reasons why he bought that program, but now it no longer matters."

Silke's eyes got visibly bigger and she shook her head slightly.

"I'm so glad you've already signed your contract," Annegret said. "I didn't want to retire without knowing that my successor would be kind to the users. However, I do occasionally have a bad conscience about manipulating you into taking this job."

Silke walked over and hugged her. Silke was always a little more outgoing than Annegret. "I owe you so much," Silke said. "I have a real job with good pay and a secure future. People appreciate me here. I never thought this would happen, and you're the reason it did."

That was another thing Annegret liked about Silke. You couldn't put anything past her. For the past year Annegret had made sure that Silke took over the care of the most important users in the chancery office, the archbishop, the vicar general. They learned to value Silke's competent and reliable work.

When it came time to get Silke the position as Annegret's successor in the library, all Annegret had had to do was circumvent her direct boss Dr. Lenhausen.

Dr. Michael Lenhausen had also been one of her student helps a number of years ago. After he completed his doctorate in comparative literature, he became the director of the library. It was customary in the chancery office, and indeed in all of Germany, to put people with doctorates in any subject into leadership positions in areas where they had no direct knowledge or experience.

Annegret hadn't warned Silke directly enough yet about Dr. Lenhausen, but she would. He would be Silke's direct boss. The man was frantically insecure, knew next to nothing about library work, and possessed a desperate and overwhelming need to be liked.

He always wanted the illusion of harmony and compromise. This made him the worst possible negotiator for the library's needs, but due to bureaucratic structures, everything had to go through him. He would remain a nuisance in the library for the next twenty years.

Dr. Lenhausen hadn't been at all helpful when Annegret told him that she wanted Silke to be her successor in the library. Loyal church bureaucrat that he was, he wanted to advertize the position nationwide and interview as many applicants as possible.

Silke was a quiet, unassuming person who wouldn't have come out on top in that kind of competition. However, she knew everything about this special library and she was kind to the users, Annegret's criteria for a desirable successor. Fortunately, Annegret was able to go over Dr. Lenhausens head and get the vicar general to give Silke Annegret's job.

"Don't work overtime," Annegret said to Silke. "We can go over the old protocols for paying the bills tomorrow. Go home. You've done enough hard work today."

Silke smiled, probably gratefully. "I do have the art appreciation class I'm auditing tonight," she said. "See you tomorrow, then." And she left.

Annegret looked at her desk and wondered if she had time to catalog a few more books.

No, of course, Lilith showed up early. Well, maybe not, strictly speaking. It was getting dark outside, and Lilith had told Annegret from the beginning that she was a free spirit whom no one could control, and that that was a good thing.

"Adam was a fool to want a subservient woman," she had announced the first time she appeared to Annegret so many years ago. "Sure, Eve did what he said, but she also did what the snake said, and we all know how that turned out."

Annegret had been immediately convinced and then grateful for all of Lilith's help over the years.

"Let's go to the reading area in the back," Annegret said. "I'll feel more comfortable there."

Lilith laughed, transformed herself into a thin, almost invisible cloud, and floated to the back of the stack room. Annegret followed her and sat on the chair closest to the front of the room.

The thin cloud solidified into one of Lilith's more flamboyant forms, a nearly naked, curvaceous, voluptuous woman with floating, red scarves that covered her breasts and genital area.

Annegret had worried about this conversation, but, of course, there was no way to avoid it. She and Lilith had been partners in malfeasance for too many years. And useful as Lilith had often been, it was never for free. Annegret always knew that she would have to balance the books some day.

"Nice of you to drop by to reminisce about old times," Annegret said.

Lilith's face turned into that of a pouty teenager. "Boring," she said. "Done is done. Been there. Done that. Don't care."

"No, no," Annegret said. "We've had some good times. Remember how you got the boneheaded director of the finance department arrested for grand theft larceny and how the police came and handcuffed him? Remember how you got the evil head of personnel fired by sending flirtatious e-mails from her account to the archbishop? Remember the tantrum she threw when they escorted her out of the building?"

Lilith smiled. "Yeah," she said. "Those were good times. Better yet, the souls of those idiots belong to me, just waiting to be plucked when our victims finally die."

"No," Annegret said firmly. "Not victims. They were the perpetrators who persecuted good people and caused them unbearable aggravation and worry. If any of these perpetrators had a conscience, I can't even begin to count how many people they would have on their conscience."

Annegret had to believe that she had been relieving people's misery with the help of Lilith's supernatural powers. It wasn't a personal vendetta when she got people thrown out of the chancery office. It was a good deed, win-win for good people, bad news for villains.

"Yeah, you keep on thinking that," Lilith said, interrupting Annegret's ruminating. Now Lilith had the face of a shrewd, heartless bill collector. "It wasn't just to help the others. You enjoyed seeing those vicious bureaucrats suffer."

"Maybe," Annegret admitted. "Still, I saved nice people from further suffering, with your help, of course. I discovered the evil-doers, but I needed you to get rid of them."

"Don't sell yourself short," Lilith said. "We have assisted each other throughout the years, though not on a fifty-fifty basis. I couldn't have placed a marker on the people's souls without your help. You know, we can't just snatch souls to torment at will. They have to make a deal, or I need physical access to their amygdalae."

"Yeah," Annegret said. "I remember how I first met you. I was back in this reading area and felt like sobbing because of what Carola Tieze told me. Frau Grob had yelled at her and berated her in the cafeteria in front of all the people in her department. Carola said she couldn't take any more, but there was no one she could turn to for help. Frau Grob was the head of the personnel department. No one dared to contradict her."

"Yeah," Lilith said. "We evil spirits get a bad rap sometimes. Actually, we generally only torment people in power, not the underdogs. After analyzing the situation, I thought you might be interested in working for me. It did take you a while to agree, but after that we had fun."

"I can only ask you to forgive my ignorance," Annegret said. "I really hadn't heard of you, and I thought only Satan could snatch people's souls."

"Satan is a wimp," Lilith said. "Always trying to buy people's souls. I just take them, with your help, of course. But that's a whole lot more fun."

"You had the idea," Annegret said. "I had always baked chocolate cookies and distributed them in the chancery office. People liked the taste of them, even, or especially the mean people."

"You had the idea of contaminating cookies for certain people with tiny mineral fragments straight out of hell. Then you followed the pleasure signals that the cookies sent to the amygdala area and you had control over the people's brains, which, of course, is where the souls are located. As a favor to me, you then arranged their workplace downfalls."

"So you did the hard work. All I did was request that you cause trouble for certain people and then distribute cookies. I am very grateful. You made my life here bearable and my work possible."

"And now you want to retire," Lilith said. "But I don't. Our deal was that you would continue to assist me as long as I was interested."

"It's time," Annegret said. "I no longer have the energy to start new projects, to promote new technological means of accessing library materials. My users deserve a younger, more energetic librarian."

"Problem solved," Lilith said. "Your successor can continue the work with me. You and I know the chancery office will always have incompetent bureaucrats in power who mistreat people. There will be people your successor will want taken care of."

"No," Annegret said perhaps too energetically. "Silke is a sweet, naive young woman. She would be shocked to learn what the two of us have done and wouldn't want anything to do with you."

"But she will need my help," Lilith said calmly. "You know how things work here. Right now, you have an archbishop and a vicar general who appreciate your library. But they won't be around forever."

"The next team of higher-ups might decide to eliminate the library. Your bean counters keep asking why the employees need a company library if they have an internet connection. And there is the excellent university library where everyone can get a library card for free. Your successor won't be able to win this fight without my help."

"She'll want to do it her way," Annegret said. "As you know, I pay my debts, and I want to balance the books as far as you and I are concerned. So my offer is that you can have my soul if you stay away from Silke."

Lilith flashed a cruel smile, and Annegret saw the genuine lack of humanity in her face. She had forgotten that deep down Lilith was an evil spirit.

Annegret held out her hand. "So, do whatever you have to do, and I'm yours," she began.

Just then, Silke came around the bookshelves. "Actually, Annegret," Silke said. "That is my decision to make, and I think I would like to benefit from the assistance that Lilith here can give me."

Annegret stared at her. "What are you doing here?" she asked.

Silke shrugged. "I've known about you and Lilith for a couple of years now. And I approve. I only wish you had trusted me enough to tell me yourself. Today I just had a feeling that you were trying to get rid of me for a reason, and so I came back."

"No," Annegret said. "Silke, you don't know what you are getting yourself into. Lilith will live forever, but, just like me, you won't be able to perform your half of the bargain once you want to retire."

"Then I'll have to make sure that my successor is willing and able to take on the job with Lilith," Silke said calmly. "Annegret, I owe you so much, but you have to start seeing me as a competent adult, not one of your helpless students."

Looking at Lilith, Silke said, "I don't have any people I want you to deal with at the moment, but you can explain how I can notify you once I do."

"This sounds like a satisfactory arrangement," Lilith said. "Then you'll be hearing from me. She transformed herself into a smoky cloud and drifted away.

"Don't worry," Silke said to Annegret. "You have taught me well. I can do this. So, get your doctor's appointment. I need you to stay alive and active for a long time. You'll have to help me get the best deals from Lilith."

Originally appeared in Lorelei Signal

[ Pikers love feedback! Comment on this article . ]