You know that feeling when you’re running out of money? I don’t mean when the money is all gone. There’s something horribly liberating about that. You don’t have money so you can’t buy things or pay bills. They want you to and you want to, but there’s nothing either of you can do about it. It’s still horrific and stressful but the panic of being on the precipice is gone. You’ve fallen off the cliff. It can’t get any worse. It is, as boring cunts say, all uphill from there.

But when you’re running out of money, that’s even worse. When you don’t know if a direct debit is going to go through, or if your card is about to be declined, you walk around all day with a weight in your stomach that drags you down to the gutter.

You know that feeling? Or, at least, you can imagine it?

Okay, well I’m not running out of money. That is a problem I’ve managed to avoid so far. I don’t have very much money, I’ll grant you, but I have a steady and regular income which my expenses do not quite exceed. My rent and my bills are paid. Twice a month I go to the cinema. I buy a book once a week. Once a month I go out for dinner, usually to a place that has some kind of set meal. While I’m there, I read one of the books I bought during the month. I visit my wife regularly in the care home. I don’t have to worry about paying for that.

So I’m not running out of money. I’m running out of something else.

I’m running out of teeth.

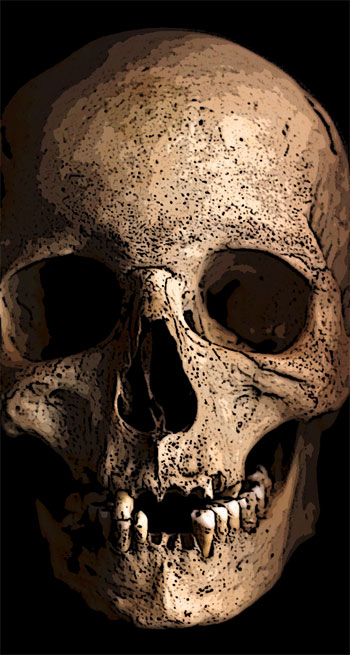

Here’s some teeth facts for you. Babies are born with no less than fifty-two teeth. All of them are stored behind the gums, slotted away in their faces like oblong Jenga pieces. If you ever get the chance, look at an x-ray of a child’s skull. It looks like something is trying to eat it from the inside-out. During childhood, twenty of these teeth emerge to great discomfort on the part of the baby. These last until early adolescence, by which time most of them should have fallen out, the body discarding them to make room for the larger and stronger adult teeth. Most mammals have baby teeth, these are also called milk teeth, as they allow space for the jaw to grow during childhood.

Some animals have unlimited teeth. Such animals are called polyphodonts. Most fish are polyphodonts. So are crocodiles. For these animals, they replace about a tooth a month. There are some mammals which are also polyphodonts. Kangaroos, for instance. Human beings, however, only get the one replacement set. We are called diphydonts. Once those thirty-two (thirty if you’ve had your wisdom teeth out in advance) come in, that’s us. That’s our lot.

My teeth came in at roughly the normal rate. By the time I was fourteen, all of my baby teeth had been shed and placed, their bloody roots carefully washed under the tap, under my pillow in the hope of a present from the tooth-fairy. By the time I was nineteen, my wisdom teeth had painfully burst to the surface. I had no need to have them removed. I read once that, in America and some other countries, wisdom teeth are removed as a matter of course, in order to avoid complications later-on. I’m glad that isn’t done here. If it was, I would be even further along the road to running out.

So, to recap, when I was nineteen, I had the full complement of thirty-two teeth. Only two of them had fillings then. By the time I was twenty-eight, I had six more fillings and one molar had suffered a root-canal treatment, a breakage, and a crown. I had also had a premolar on the other side removed when it got infected on holiday in Turkey. And so, I had thirty-one teeth left

In Turkey was the first time I had ever had a tooth pulled. I know some people have to have some of their baby teeth pulled if they are stubborn or causing the new teeth to grow in at odd angles, but all of mine fell out and were replaced exactly as intended. I only knew about having a tooth pulled in the proverbial sense. In casual speech, having a tooth pulled is proverbially the worst thing that can happen to a person. The thing is, people also say that about root-canals, and I found mine to be largely pain free so I wasn’t overly worried about the tooth pulling.

In truth, I didn’t have much time to worry about it. The wait between the decision, made upon the advice of an unsmiling, large Turkish dentist with hair that fell in a neat braid almost to her backside, and the execution was as long as it took for the dentist’s pretty young assistant to close the door to the examination room and bring her a tray of metal tools. I would like to exaggerate and say that the tools were covered in rust and the dentist was the spiritual sister of the guy from the Shop of Horrors. Doing so would, in some ways, make me feel better about how horrible the experience was, since it would make it make more sense. The truth was, however, that the dentist was a perfectly capable woman whose face was kind despite its lack of smile and whose touch was gentle and professional, and the tools and the examination room itself were both gleaming and gently cooled by the continuously running air-conditioner set above the door. The vibe it gave was more that of a hotel room than of a torture chamber.

The dentist numbed me first. The injection was painful and the needle was huge, but the pain only lasted a few minutes before the numbness started to spread. My upper lip began to feel puffy and huge, as if I had something strange and heavy stuck to my face. Then she began. I got only the smallest glimpse of the tool she selected – something which looked like a long pair of pliers but which I now know is called a tooth-extracting forceps – before it disappeared into my mouth and she bent over me, a small frown on her face while, at the other side of my mouth, her assistant slipped in a small suctioning hose which immediately stuck to my tongue.

Her work was indetectable to me at first, aside from the discomfort of keeping my jaws wide, and the occasional clatter of her instruments against my other teeth. Then, it began in earnest. I felt the pull. She reared back slightly, and I could see the muscles of her shoulders bunching as she yanked. Her wrist rotated, and I heard two cracks in succession like the breaking of a bone. I suppose it was the breaking of a bone.

Then the pain began.

Pain like that overwhelms the senses. All five of them are on one mission; that of screaming their complaints at the agony. My vision blurred and I couldn’t hear my own screams. My hands clenched and I could smell the sharp, metallic scent of blood. It tore at me, clawing at my body like a thousand rats. I wet myself a little bit, and my toes clenched so sharply that I bent back one of my nails.

The dentist didn’t stop though. I don’t know why, as she didn’t really have the English to explain. Maybe she thought that it would be more painful to stop, inject more painkiller and start again than it would be to pull through. Either way, she kept pulling and I, for some reason, kept my mouth open to allow her access, moaning and screaming all the while.

When it finally came out, it came all at once, so suddenly that I was surprised it didn’t make the sound of a champagne cork popping. The dentist stumbled back a pace, a dripping mess clutched in the forceps and blood began to rush from the hole left behind. I tasted it immediately as it bathed my tongue. It tasted almost like meat. Then the suction from the dental assistant kicked in and the worst of it rushed down the tube, moving from within my veins to a medical waste bin in a matter of seconds. I felt strangely bereft at its loss.

The recovery period was fine with the help of liberal amounts of clove oil which, as someone who has now had thirty extractions, I can assure you really does make you better, and some rest. After that, I was back to normal and I could even enjoy the rest of my holiday, though my tongue continuously poked in and out of the space that was left.

I couldn’t forget the pain though. I never forgot it.

But enough about that. Here’s an important question for you. Do you believe in God? That’s a big question, I know, so don’t feel obligated to answer. Perhaps it is one of those questions that we should never ask each other. Still, it’s important to have a think about it, even if just for the purposes of the story I’m telling you. For my part, I do. When I was younger, I believed what they told me about Him in school. I believed that He was a loving God who only wanted the best for us. I believed that He always watched over us. I don’t believe that now. Now, I believe that God is violent and vengeful. I believe that, insofar as He ever pays attention to us at all, He looks at us with a malevolent eye. I believe He wants to harm us. However, I also believe that He is always up for a deal. A covenant, if you like.

If you think that this seems like a pretty bleak and cynical view of life, then you would be right. If you wonder what the fuck it has to do with teeth, I’ll get there in a minute.

First, as to my being a cynic, that is true. I am. Cynics aren’t born, though; they’re made. People with easy lives find it easy to think that God is good, because He has always been good to them. This is the same attitude as you find in people who say a man couldn’t possibly be beating his wife because he is so nice at work. Those of us who know, though, how cruel God can be, know better. When you have felt His eyes upon you and felt His hate, you learn to fear Him. Not love Him.

Let me give some backstory about my wife. It is important to give backstory when you are telling people a story. It allows them to see the characters as entities who exist outside of the confines of the page and the events it describes, and can help illuminate the story you are telling. With that in mind, I’ll keep this short. It’s for illumination purposes only.

I met my wife, you don’t need to know her name, four years ago. I met her at work, which is apparently less and less common now with internet dating. I’ve met people on the internet too, but none of them clicked with me like she did.

I noticed her as soon as I started, though she doesn’t believe this. She says I’m just trying to sound more romantic than I am. It’s true though. The reason I didn’t approach her is that I wasn’t sure if she was gay or not. I was never very good at telling. She doesn’t believe that either, but there you are. She worked in the same team as me but we didn’t have a huge amount of work together. Despite this, she began to notice that I was always somewhere nearby, waiting to ask her opinion about something pointless or ask her to sign off on something that didn’t concern her. I was never the subtle type.

We were married nine months later.

Forgive me if I don’t spend too much time on this. I want to get to the point as soon as I can and, anyway, happiness doesn’t make for a good story. That’s why they put “and then they lived happily ever after” at the end of the book, not at the start. Suffice it to say that we were happy. Very happy.

Then, as must happen after every “happily ever after,” it all went wrong.

Would it help you to know the disease? Would that make the story more believable to you? You may tell yourself so, but the truth is that, unless you’re a doctor, it’s very unlikely to make a difference. The important thing was that she was sick. Very sick. Dying. Dying in the body and in the mind. Every week, she wasted away physically and her brain and self wasted away with it. She could remember me sometimes, but less and less often.

I cared for her as long as I could. I want you to know that. That’s much more important than exactly what the disease was, don’t you think? It tells you more about me. I cared for her until my boss sat me down one day and told me that, if I was late one more time, it would be a disciplinary. After that, he didn’t know what would happen. The implication was that it wasn’t good. I had to face the fact that I couldn’t care for her any more and that things weren’t going to get easier. They were going to get harder, and that was why I decided to put her in the home.

It’s not really a home. It calls itself an end of life treatment facility. It’s a private one and it’s expensive. I sold our house to pay for it. I never told her, in her lucid moments, that I did this. That would have devastated her more than anything, I think. Maybe even more than me abandoning her in a home. The place is nice, though. That’s what I tell myself. It’s more like a hotel, albeit a dated one, than a hospital. The nurses all seem kind too. I’ve never seen any of them treat her with anything less than respect. Not once.

The day I put her in the home and left in the evening, she clung to me with crooked, jerking fingers, hooking them into my jumper. She didn’t look at me as she did it. Her face was blank and she was gone to wherever it was she went when she wasn’t with us. Somewhere deep in her mind. It took the nurse five minutes of patience to disentangle her from me. I cried the whole time. You don’t expect to be doing that when you’re twenty-eight.

That day was when I learned how awful God was. That was when I learned what happens when you attract His awful attention and His eyes are upon you. That’s when I learned God wasn’t kind. I didn’t ask Him to help, though. Not then.

A year passed with her in the home. I visited every day I could, and always on the weekends. When I came, I would stay for at least an hour, even if she was semi-catatonic. I think it soothed her to have me near and the nurses agreed, though they likely said that to all the family members who asked. When she wasn’t able to talk, I would read a book on my kindle and hold her hand. Sometimes I would read it aloud to her. Of course, that was when I still had all my teeth, There were times when she was herself. They happened now and again. Usually about once a month, I would turn up and it would be like nothing had changed. She would chat away to me as if we weren’t sitting in a strange room in a strange place she would never leave. Often though, increasingly often, these visits would draw to a close when, suddenly, her personality was gone and drained from her body like a tap. Sometimes she would wet herself when this happened.

I know what a hospice is. Of course I do. I knew that she would eventually die there. That was the whole idea of the place. I knew this, and yet as the day got closer and closer and I could feel it coming like the tingle you sometimes feel in the air before a storm, I couldn’t accept it. Can anyone? I suppose they must be able to because you don’t see too many people walking around with no teeth these days. But how? I can’t imagine how you can just accept that the person you love is going to be gone and there’s nothing you can do about it. I don’t understand it.

I couldn’t accept it. I wouldn’t. I won’t.

The breaking point came when I moved into the third month since I had seen her be anything but catatonic. The nurses told me that she was now exclusively in nappies – previously, she had been able to wipe herself most of the time if nothing else – and they began to feet her intravenously. The doctors began to have delicate talks with me about Do Not Resuscitate orders, all of which I refused to sign. But even I could see that the time was coming when I would have no choice but to do it. The time when doing otherwise would be nothing short of cruel.

That was when I asked God for help.

I had never really prayed before. I think most people probably haven’t. Even if, unlike me, you grew up with parents who were religious, I think the average person has never really prayed and expected an answer. At best, they have went through the motions, or recited some prayers that they have been taught in school or in mass.

That wasn’t what I did. I actually spoke to Him like He was a person I could see and touch. I think that’s what made the difference. I did it in a church one Sunday. I waited until mass was done and all the people had streamed out, then I slipped in at the back of them. There was a mass at 10am and one at 12. For the hour in-between, the church doors were left open for private worship. The only other person there when I got in was a cleaner who was rolling out a huge length of cable for an industrial hoover. She went up to the altar, genuflecting first, and then seemed to find a plug set amongst the marble somewhere. The hoover roared to life, noisier than it seemed anything should be in a church, and she got to work, starting with using the hose on the carpeted altar stairs. She didn’t look at me.

I sat near the back of the church and looked at the paintings on the walls. I remembered enough of school to know that these depicted the stations of the cross. I used to know them all in order. I won a pencil for memorising it at a school retreat. The one beside me was ‘Jesus Falls for the Third Time.’ In the painting, Jesus, clad in blue and red, was half-pinned beneath a black cross. There were others around him lifting it from his body. A Roman soldier clutching a whip stood by at the side watchfully. I wondered if Jesus felt then as I did now. Empty. Despairing. Weak. I lifted my head and I began to pray.

The prayer I said wasn’t really a prayer at all. I closed my eyes and I begged. I begged that she be made to feel better. I wasn’t being greedy and all I asked for was that, sometimes, I would get to see her as she had been. That sometimes she would remember me. I sat in the empty church with the hoover screaming in my ears and I thought of the nameless thing which stood above me and I begged Him to help me.

You can imagine my shock when He answered.

This is when I thought I might start to lose you, but stay with me. Consider why you’re so sceptical that God answered me. Presumably, you accept it when people say they are praying. Do you really think it’s more crazy to be praying into thin air without ever expecting an answer than it is to receive one? If you don’t expect to be answered, then why are you praying at all?

I’ll admit that I’m being a bit hypocritical by trying to take the high road there. The truth is, I was as surprised as you were when He spoke. But I couldn’t deny that it happened. My first thought was that I had mistaken the sound of the hoover’s suction. The second was simply that I had lost my mind. It may be that, by the end of this story, you’ll agree with the second thought. I don’t know. My goal isn’t to convince you that I’m sane. It’s only to tell you the truth.

At any rate, I dismissed the voice when I heard it at first. Whatever it was, I didn’t think it was worth paying attention to. Perhaps, if the monster we call God had decided to leave it there, I wouldn’t be telling you this story. As it was, He didn’t give up.

Yes, the voice said again in my ear. It wasn’t a deep man’s voice as I had imagined the voice of God might be in my childhood. If it sounded like anything, it sounded like my own. I suppose that made sense. The voice came more from within than from without, as if a thought had been sent echoing through my brain, and so it stood to reason that it would have a lot of me in it.

The “yes” wasn’t a question, as if I had interrupted Him in the middle of doing something else and He was asking me to repeat myself. The “yes” was a simple agreement. It was an answer to my prayer.

My hands, which I had almost unconsciously clasped in front of me when I started praying, slowly lowered and I opened my eyes. The woman doing the hoovering was working on the aisle now. Her biceps flexed under her blouse as she brought the hoover back and forth over the deep blue carpet. She glanced at me without interest and gave me a brief smile. I returned it uncertainly.

There was no repeat of the voice for a few minutes and I almost laughed. I had managed to trick myself into hearing voices twice in the space of two minutes.

I am here, the voice said. It was huge in my mind and blotted out other thoughts. I took in a breath and I could feel tears at the bottom of my eyelids threatening to overspill.

I am always here, the voice said, and the answer to your demand is yes. I will grant a boon to you. All you need to do is grant a boon to me in return.

And the voice slowly explained to me in the dim church, what He wanted in return. By the time He was done, the hoover had been stowed away and a couple of early birds had started to appear for the midday mass. These looked at me with a slight annoyance, as if my unexpected presence disturbed their usual worship. Perhaps they were annoyed that I was there before them. I ignored them, though. I was listening to the slow and thoughtful voice in my head.

The deal was simple. A blood sacrifice for a month’s reprieve. And not just blood. It had to be a part of me I could never get back. The voice wasn’t specific as to what, but I had seen enough movies about summoning a demon to get the gist. You might hear this and think that it sounds more like something a demon would demand than a God, but you would be wrong. It’s all in your Bible. God used to love a human sacrifice now and again, and now all He was asking for was a little bit of me. A little bit of me for all of her.

There was no doubt in my mind, as I went home that morning, that I would do as the voice asked. Perhaps I had gone mad. Perhaps I have stayed mad. All I knew was that this voice had offered to help me, and all I had to do was such a small thing. I decided on a tooth as the sacrifice before I reached my front door. The human body has thirty-two teeth, and I still had thirty-one. That would give me thirty-one months.

I did the first one that very day, afraid I would lose my nerve. There was no special prayer. I didn’t have to draw a pentagram or whatever crazy thing you’re thinking. All I had to do was kneel down on the bathroom tile and reach into my mouth with a pair of needle-nose pliers.

The first extraction was messy. Messy and painful. After that one, I ordered some tools online. You can get dental foreceps for £17.51 on Amazon and, believe me, if you’re planning to pull teeth, they’re a bargain. I knelt on the bathroom floor and thought of my wife. That gave me the strength to begin.

The tooth came out, and the blood followed. I knelt on the floor, blood pouring from my mouth like vomit and pooling around my bare hands. I was crying but barely aware of it. My tooth and the pliers cluttered heavily to the floor. The pain ripped through my body and shredded my mind like paper. There was only space for one thought to echo over and over again.

There, you have it, now give me your part of the deal.

I slumped there on the floor for almost an hour, dribbles of blood trickling from my lips, unable to force myself to move. Then, a buzzing from my pocket. My phone. With blood-soaked hands, I dug it from my pocket, but the blood stopped my phone from recognising my touch. Desperately, I used my nose to slide the answer button across the screen and held the phone to my ear, blood dripping from my fingers and my mouth.

I spat as quietly as I could and said, ‘Hello?’

My voice was muffled and sounded strange to my ears but the person on the other end of the phone didn’t seem to notice. She explained that she was calling from the hospice and that my wife was especially bright today and had been asking for me. I had told them to call me if ever this was to happen. I said I could come in a couple of hours She said that she thought my wife would like that.

That day, my wife was as well as if she had never been ill. We talked and we laughed, and we kissed and we both cried. I felt the space where the tooth used to be and thanked God. It had been such a small sacrifice, in the end. And He had given me so much in return.

But it didn’t last. As the month went on, she flagged, and by the last day of the month she was worse than she ever was. I spoke to God again and He told me that he wanted more. That he would want more every month.

So I pulled another tooth. And another and another and another.

Each time I did, I would receive a call within the hour telling me that she was better. And I would go to her and we would be together. I learned to enjoy the first five days of each month, and to ignore the agony I was inevitably feeling at that point. I also learned to pull teeth with as little pain as possible, though, in truth, it got a little bit easier each time. Each tooth seemed looser than the last.

It has been twenty-eight months since that happened. That’s more than two years. And I’m running out of teeth. I have three more left. After tomorrow, I will have two. That’s three more months with my love. And after that, I don’t know.

I suppose the fingers will take me through to Christmas.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.