It was decided. They would hunt down the bastard even if it meant going to Patna. Goithas glowered under garlic-studded brinjals, potatoes, tomatoes and chillies as Tantan chacha blew into the kadhai, fanning occasionally to kick-start the desi oven. It was his idea, outsourcing the manhunt to his old comrades in the state capital.

“I say we get him unawares. Bastard would be chilling with his pile of stolen books when my comrades raise hell on his ass. Won’t even know what hit him.” Tantan chacha outlined his surgical strike, picking a hot goitha by accident and almost burning his hand.

“Has violence ever solved anything? Mature adults find peaceful solutions. Let me handle this. Bastard will come around as soon as the mayor steps in.” Gulshan chacha pitched in his Gandhian wisdom.

Having discussed the matter with his trusted connections in the municipal corporation last night, Gulshan chacha was convinced that only the mayor could help them locate the bastard, that the unwavering official could be moved with ghee-laden littis, tangy baigan-alu-tamatar chokha and dollops of good old flattery.

They huddled around the kadhai, kids on their haunches, chachas on plastic chairs, taking turns to warm their hands in the chilly December night as sattu-stuffed littis on newspaper sheets awaited their turn in the makeshift oven.

It was the winter they had discovered masala cold drink. Ankur, having spent diwali and chhath puja at his nani’s place, had returned with tales and recipes. The most captivating was masala cold drink. Chilled Coca Cola poured on ice cubes with a spoonful of chaat masala and jaljeera powder. Optional: crushed mint leaves and lemon juice. It was rocket fuel after a hearty litti chokha dinner, for it sent the grey cells running like nothing else.

Abhi and Akhil peeled the charred vegetables, passing the pulp to Sanju and Manpreet who were mashing and mixing it all together with garlic, chillies, salt and mustard oil. Prateek and Karan were playing salad ninjas with onions, tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots and radishes. Ankur had been sent to get dahi from Gulshan chacha’s pantry.

Gulshan chacha and Tantan chacha weighed options to recover the missing books while carefully assessing and turning the half-done littis on the goithas. It had all begun that summer at the Ramakrishna Mission Ashram.

* * *

It was the first day of summer vacations. Akhil was taking an afternoon nap when Nitin broke his siesta, ringing the bicycle bell and calling repeatedly from outside the window. Dazed and confused, Akhil was still processing if it was the same evening or whether he had slept through the night when Nitin stuck a paperback in through the window bars.

“Return this to the Ramakrishna Mission Ashram library by tomorrow. I’m leaving for Kolkata tonight. Cousin’s place, remember? Will be back in July. Do read the book. The movie’s good. But this is the real shit.”

“Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Wait. This is like… 350 pages or something. How do I finish it by tomorrow evening? And I haven’t even read the first two books.”

“Trust me, man. It’s that good. But do return it by tomorrow or they’ll fine me. Ask Abhi. I’ve seen him often at the ashram. He’ll take you there.”

Nitin pedalled away without waiting for an answer.

Nitin bhaiya, always in a hurry. Akhil thought. Nitin was his senior at school. Akhil was in class 8, Nitin in class 9. What was that he had said about Abhi? There was an ashram? The ashram had a library? Abhi had been there? Why hadn’t Abhi told him? He was his best friend. Akhil splashed water on his face, rubbed it dry with his mother’s dupatta hanging next to a clean towel, took a water bottle from the fridge, looked around for witnesses, then drank with his mouth kissing the bottle’s. Having refilled the bottle, he checked on his parents and younger brother dozing off in the other room, then left, leaving no clue or witness.

He reached the cricket ground at around 4:30 in the evening. The boys had arrived. All except Abhi. Their opponents were a team of boys from the other side of town. They were taller, older, undefeated. Akhil was leading the charge from his side since there was no sign of their captain, Abhi. They won the toss and decided to bat first. They were 3 wickets down for 32 in the sixth over when Abhi arrived, panting. He had another ingenious excuse ready. He had left home right on time and was zooming his way out of the mohalla when Mr. Agarwal, owner of the corner sweet shop, saw him and started begging him to look after the shop until he relieved himself of nature’s call. And boy what a long call it was! Vintage Abhi. The boys thought and continued with the game.

Akhil had opened the innings and was run out in the first over. His head was not in the game. He had told the boys of Nitin’s visit and was encouraged to at least give the book a try, even though he had watched the first three Harry Potter films. They were all out for 67. Abhi, their star batter late to the party, had added 21 crucial runs batting as a tailender. The opponents chased the target in just over 6 overs. Disheartened but not surprised by the result, the boys snacked and chatted for a while at the chaat–phuchka stall outside the ground, then left for their homes.

Back home, Akhil sat with the book and stayed awake until four in the morning, cursing his school for being nowhere as cool as Hogwarts. He was up again at seven, rushed through breakfast and by 2 pm had devoured Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. It was an epiphany. He had to visit the ashram now. There must be more books in the library. Also, he wanted answers from Abhi.

* * *

The five of them—Abhi, Akhil, Karan, Manpreet and Prateek—reached the ashram at 4 pm sharp, the time the library opened in the evening. Along the way a confession had been extracted out of the backstabbing Abhi. It turned out that Abhi was already a member at the ashram library. He had been making rounds there for weeks, hoping to woo a girl he had his eyes on. The girl was a regular visitor and would sit for hours reading English novels. Abhi, who’d barely touch his textbooks, had memorised author names, book titles and plots of dozens of British and American classics at the library, awaiting the fateful day when the girl, intrigued by the mysterious, handsome nerd, would initiate a conversation, and he would turn around, slicking his hair back, and say, “Call me Abhi.”

The ashram was magical, so was the library. Gulmohar trees in full bloom lined the road to the main campus gate. Inside, a paved pathway flanked by trees and shrubs diverged, one leading to a medical centre, the other passing by the library and a couple of classrooms before taking a sharp bend to a garden, temple and the monks’ residential quarters. The boys cursed Abhi for having kept the existence of this utopia from them for so long.

Returning the book, they found out that they could get a library card for a nominal, refundable deposit and could borrow two books at a time for 15 days. All of them had their cards made.

It was the summer of their reinvention, the summer they graduated from comic books to novels—not that they stopped reading the former. The first thing they did with their new library cards was read the first two volumes in the Harry Potter series, the others except Akhil read the third one too. Then they discovered countries, mountains, jungles, deserts, oceans, everything else under the sun, and many other suns in those bookshelves. Karan, who was more into weird stuff, found an illustrated book on some “Austrian” guy called Sigmund Freud. He was sure it was a printing error; it should be “Australian”. The book had sketches of naked women that demolished all of their prior assumptions about the female body. Then there was a copy of the Guinness Book of World Records—a big, fat book they had to stretch open on the table with both hands—with a full-page photo of a woman named Heidi Klum wearing the world’s most expensive bikini, studded with real diamonds. Diamonds were the least interesting things on that page.

That summer alone they read more than two dozen novels, Agatha Christies and Conan Doyles, mostly. Ruskin Bond and Satyajit Ray taught them that India was no less interesting. It was Enid Blyton who introduced them to full English breakfasts which, although they sounded ample, made them wonder what the hell the British did with all those spices they had fooled around in India for for over 300 years.

Manpreet found an old copy of Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, featuring James Bond. They jumped in expecting the ride of a lifetime but came out disappointed, unable to understand the hype about 007 when all the world’s greatest spy would do throughout the novel was get spanked by the villain on his bare arse.

One evening Prateek arrived at the cricket ground with a thick volume. He had to be calmed down with a glass of water, for he wouldn’t stop singing praises for “Don Quick-zote.”

They would spend most evenings talking to the monks at the ashram. To their surprise, none of the monks forced the spiritual path upon them; they were men of science and cinema. The monks told them of the mysteries of the universe and their favourite filmmakers, recommending works by the likes of Stephen Hawking, Richard Feynman, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, James Cameron, and more. The head monk, affectionately called “Chicago waale baba” (“The Saint from Chicago”), was an American. For some reason the boys would stare at him from afar but could never gather the courage to approach the “angrez baba” (“foreigner saint”).

Like all good dreams, vacations were over. Consuming an unusually high dose of literature in the span of a few weeks had a curious effect upon the boys—they wanted to be writers now. Karan’s first piece of non-fiction—a scandalous essay satirising the paralysed jalebis their school served the students after Independence Day parades—had landed somehow on the Principal’s desk, earning him an earful and a parent–teacher meeting. Manpreet’s first poem—a mock-heroic in iambic pentameter titled “The Fucking Man Cometh”—made him a rockstar, getting passed around amid loud cheers from the boys in his class. Intense envy emanated from girls dying to discover the contents of the heavily-guarded piece of paper which was ultimately snatched away by the English teacher who, upon reading it, tore it to bits, never speaking of the incident again. Front-benchers vouched that there had been a momentary smile—one of immense pride—on the teacher’s face when he discovered his pupil’s bawdy genius of Shakespearean proportions.

Akhil was all thanks and regards when he met Nitin at lunch break one afternoon. Back in town, Nitin was happy to see that his favourite junior had heeded his advice. He asked Akhil if he had also read the fourth Harry Potter book.

“What fourth book? There’s a fourth book? Where do I get it?” Akhil asked.

“Why, at the library! It’s called Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. I thought you’d have read it by now. Who stops after reading the first three?”

“I didn’t see a fourth book. You sure about that?”

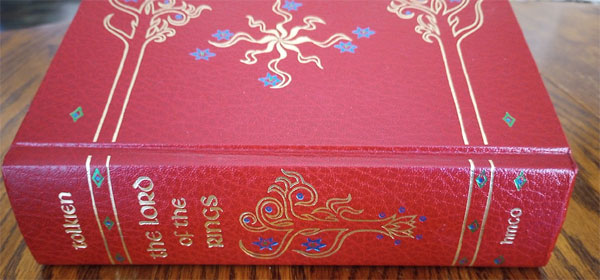

“Dude, I read it last year. It’s right there on the shelf where they keep the Harry Potters and The Lord of the Rings. You have read LOTR, right? It’s better than Harry Potter.”

“Bhaiya, there is no fourth Harry Potter book. And no lords and rings on that shelf!”

“What? Let me have a look this evening. Must be on some other shelf.”

That evening the six of them searched every shelf in the library but couldn’t find the books. Prateek requested the librarian, a young monk in his late twenties, to look into his register. It turned out that the two books had been issued to someone named Sam about eight months ago and the bastard had never returned them. The librarian told the boys that the ashram was more concerned with spiritual matters than mundane. Hence, there had been no attempt to recover the books. The boys’ repeated requests for the bastard’s address were denied on member confidentiality grounds.

Months of patience and careful plotting bore fruit. One lucky December evening Abhi managed to steal the bastard’s address from the register when the young monk, out on bathroom break, had forgotten to lock his desk drawer.

Prateek noticed that the bastard’s signature was the dollar-like “S” from the comic book store’s register, which meant it was the same bastard who had borrowed the eagerly-awaited, multi-starred comic book two years ago and was never seen again.

A fire raged in them as the boys burned with vengeance, eyes sparkling with anticipation of the adventure of a lifetime.

* * *

The address was of a riverside house. They were beaming at the thought of roaming through the oldest part of town, by the river, along the ghats, with buildings and temples pre-dating the British. The only problem was that the old town was a maze of narrow lanes and alleys that all looked the same. There were no house or street numbers, and all landmarks were temples and ghats that were identical and aplenty. None of the boys had yet been able to decipher that part of town, and they couldn’t ask Gulshan chacha or anyone else in their families to help them look for the bastard’s house in that cradle and labyrinth of civilisation.

“Are you guys insane? That’s a red-light area, you dumbasses. Gulshan chacha’s wife will wash him and hang him inside out to dry if she gets word he has been there.” Akhil explained the situation to his friends who were expecting his uncle to be their guide on the riverside expedition.

“It used to be a red-light area, briefly, during British times. It’s not tainted anymore.” Abhi protested.

“Sure, you think you can convince Gulshan chacha’s wife that her husband went down the riverside to meditate on the ghats?”

All uncles were out of the question. There was only one guy who could help them now. A guy who lived by the river and used to be their friend.

“Khan hasn’t talked to us in over a year. All because of this idiot Manpreet.” Prateek smacked Manpreet on the back.

“Told you guys like a million times. It was a prank. Who gets offended over a silly prank? And who would be silly enough to even fall for that? No wonder they call him mental.” Manpreet remembered the events, blocking Prateek’s punch down south, a proud smile colonising his features.

* * *

Mukammal “Mental” Khan was their classmate and friend from the riverside. He was inseparable from the gang, nicknamed so for his erratic actions and words free from confines of time, place and company. His nimble mind and reckless tongue had got them into trouble on numerous occasions.

Over a year ago, when mobile phones had arrived only recently in Indian towns, Manpreet’s father, a businessman, had got himself one. Delighted upon discovering that Mukammal too had a new phone in the family, Manpreet was about to ask his friend for his number, until he got a better idea.

Getting the number from a mutual friend, Manpreet called Mukammal one day, impersonating a girl the latter had a huge crush on since kindergarten. A telephonic love affair ensued. The two boys lost sleep, appetite and sense of time over the next few weeks—Mukammal struck by Cupid, Manpreet by Loki. Secret confessions and promises of happily-ever-afters led to the inevitable rite of passage—the meeting in the park. Mukammal was beaming with joy that his lady love had consented so easily. He was to wear his flaming red shirt with a red rose in the shirt pocket. His beloved would be dressed in pink.

Manpreet had planned for the grand denouement to take place in the park amidst friends laughing and apologising for breaking Mukammal’s heart. But Mukammal’s childhood crush, the real one, happened to be in the park that evening, strolling with her girl friends, incidentally dressed in pink. No sooner had he caught sight of her than, true to his nickname, Mukammal was down on his knees popping the question, a red rose in his outstretched hand.

A public slap and private realisation later, Mukammal Khan was no longer friends with Manpreet, and by association, either of the boys in the gang.

* * *

Four samosas, two alu chops, twenty-six phuchkas, one full-plate chhole tikki chaat, four gulab jamuns, a glass of lassi, three big burps and a long, subdued fart later, they were friends again.

They followed Mukammal through the narrow identical alleys in old town, past houses, shops, temples, and ghats that appeared at the end of each alley.

“Every civilisation has been founded near a river.” Mukammal’s history lesson fell on ungrateful ears.

“What about desert settlements? Did they begin near mirages?” Manpreet was in no mood to respect the reunion.

“Fuck you.” Mukammal said, refraining from sharing cultural insights for the remainder for their quest.

After what seemed like eating their own tail for over half an hour, Mukammal stopped his bicycle at the entrance to a narrow alley, and said, “Go straight down this one. Take the second left. Then, third right from where the lassi shop is. The address says ‘behind the crooked banyan tree.’ That’s where you’ll find your tree. There’s no pucca road to lead you to the house. Leave your bicycles under the tree. Here, secure them with this chain and lock; these are badlands. Then follow the muddy slope from the tree to the bastard’s house. Watch your step. The slope’s slippery and drops straight into the river. One bad step and you’ll be in Bangladesh without a passport.”

“You’re not coming with us?” Abhi asked.

“Something came up. Can’t explain now. I’ve told you guys all you need to know.”

The boys followed Mukammal’s instructions. They were told upon reaching the house that nobody named Sam lived there. The only guy in the family of seven sisters—a boy aged 25—had left for his grandparents’ place in Patna last week.

“Bastard got away this time. What now, guys?” Abhi asked on their way back to where Mukammal had left them.

“We’ll think about it over litti chokha tonight. Tantan chacha is cooking. It’s Gulshan chacha’s treat. Where’s Mukammal? He’s also invited.” Akhil readjusted his glasses, hoping to spot their deserter friend somewhere in the market.

“What’s that commotion over there?” Karan pointed towards a crowd gathered around a wall a hundred feet or so from where they stood.

They arched their necks trying to zero in on the subject of the crowd’s attention. Prateek and Manpreet elbowed their way through the crowd, clearing a pathway for the boys.

On the other side of the crowd Mukammal rose from a dirty, stinking drain like Ursula Andress from her sexy beach scene in James Bond’s Dr. No. His bicycle, covered in slime, lay at an awkward angle in the open drain. Bystanders told them how the boy on the bicycle had been following some girl in the market, eyes on her all the time, when he fell face-first in the drain.

Akhil helped his fallen friend to his feet, signalling at the crowd to get the bicycle out.

“I was gonna invite you over litti chokha tonight. Guess you won’t be coming now?”

* * *

Litti chokha and masala cold drink had sobered their senses. They no longer saw merit in armed raids or political intervention. Peaceful discussion should work just fine.

“And if there’s need for persuasion, I’m coming with you guys. We’ll make the bastard tow the line.” Gulshan chacha downed his sixth drink and threw the disposable glass in a corner.

“I’ll pack a bag with supplies.” Tantan chacha said. “All you lads need now is your parents’ permission.”

The party dispersed after deciding to meet again at 4 am. They were to take the morning bus to Patna.

* * *

The boys arrived outside Akhil’s house at 4 am sharp. Mukammal, feeling better after yesterday’s public humiliation, had managed to get the bastard’s Patna address from a disgruntled neighbour of his. They could finally read Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. And there was more magic and adventure to be discovered in Tolkien’s timeless tale.

“Nitin bhaiya says The Lord of the Rings is even better than Harry Potter. I’m not sure. We’ll find out soon.” Akhil beamed.

“It can’t be! We’ll see which one’s better. Where’s your uncle? We’re gonna miss the morning bus, thanks to him.” Abhi glanced at his watch.

There was no word from Gulshan chacha. He should have arrived by now.

Worried, Akhil went to Gulshan chacha’s and returned fifteen minutes later, crestfallen.

“It’s all over, guys. Looks like Gulshan chacha’s mom wasn’t all too pleased with ‘a 33-year-old man running around with kids, trying to be one.’ He ain’t coming with us. In fact, we’re not going anywhere either. The old lady gave her son a good thrashing and threatened to tell my father all about our plan.”

“Damn our luck! Did you talk to him? Any chance he could sneak out?” Manpreet asked, still hopeful.

“He says last night’s heavy dinner gave him gas, that’s why he can’t come with us. It was his wife who told me about the thrashing. Should have seen his face when she was spilling the beans.” Akhil let out a feeble smile.

“There goes a dream.” Prateek sighed. “What do we do now?”

“Have you guys heard of a PDF? It’s this new technology where you can read a book on a computer. And you can print it on paper too. Like a real book. There’s a new cyber cafe near my place. We could try that.” Karan offered a silver lining.

“But how do we get a pee-dee-ef? None of us are computer geniuses. Guys our age in Delhi are doing all kinds of fancy stuff with computers and mobile phones. And we’re stuck in Bihar with our comic books, magazines and paperbacks.” Prateek lamented.

“Leave that to me. Your brother Khan here will get you guys all the pee-dee-efs you want.” Mukammal announced, expecting bravos but not getting any.

It was decided. They would assemble at Karan’s at 5 pm. Then the last dance at the cyber cafe.

* * *

“You? Out! All of you! Don’t you dare come anywhere near my shop or I’m gonna speak to all of your parents! And you, Karan! How can you be friends with this one?”

“What’s the matter with him? Is he mental or what? He didn’t even let us in and he’s like...” Karan said as the boys were driven away by the furious owner of the cyber cafe.

“He is mental. I was just looking at some pee-dee-efs before you guys arrived and the computer started showing women in swimsuits with Gryffindor and Slytherin scarves... I mean... Dude himself has faulty computers but is acting like he’s a lord of the ring or something. Don’t you guys think Hufflepuff is underrated? None of the women—” Mukammal cleared the air, receiving kicks and punches and curses from all.

“Whoa! Easy there, guys! Your brother Khan here will beg, borrow, steal if he must to get you the books.”

“Borrow! We can borrow.” Manpreet mumbled.

“What?” The boys turned.

“I think I might know someone we can borrow it from.”

* * *

They stood in front of a white colonial-style bungalow with barbed wire and bougainvillea crowning the outer walls. Two uniformed men with rifles guarded the big iron gate. A sign the size of a car window said “BEWARE OF DOGS.”

“You sure this is where she lives? Since when did posh girls start making friends with you?” Abhi winked at Manpreet.

“Shut up, fucker. Our families go way back. Her grandfather and mine were friends. We’re lucky she’s in town at her aunt’s for Christmas and agreed to meet you idiots. She owns hundreds of books from what I’ve heard.”

“Did you ask if she has the books we need?” Karan enquired.

“I did.”

“And? She has ‘em?”

“She neither confirmed nor denied. But she agreed to talk to us.” Manpreet said.

“Let’s go talk then.” Karan started walking towards the guards.

“Wait. Let me handle it.” Manpreet went to the guards and said something inaudible, to which one of them pulled out a walkie-talkie and upon instructions from the other side, motioned the boys to enter.

To their awe, the gate opened without the guards touching it.

“Remote-controlled.” Manpreet bragged.

Inside, a pebble-lined driveway wide enough for two cars meandered its way to the big white house surrounded on three sides by a garden with date palms and other exotic plants.

They were led by the gardener to a thatch-roofed outdoor sitting area and seated in cushioned armchairs. The boys realised their necks’ untapped degrees of freedom trying to steal glimpses inside the house. They could confirm a Bruce Wayne-style grandfather clock and a grand piano straight out of horror movies in what appeared to be the living room. A middle-aged woman dozed in a lounge chair, the inimitable Mohammad Rafi serenading her on a gramophone. Outside, the gardener was playing fetch with two Dalmatians that looked more pampered than the boys.

“Manpreet, you brought us to Aunt Cruella’s lair?” Karan’s joke had the boys in splits. It was lost on Mukammal until the reference landed and he joined in the laughter.

“Talking behind my auntie’s back, eh?” The alien voice took them off guard.

“Err, we were just...” Manpreet grasped for words.

“Nevermind. It’s good to see you after a long time, Manpreet.”

“Lifesize... I mean likewise.” Manpreet fumbled. “Guys, this is Priya, my... err...”

“‘Friend’. The word won’t burn your tongue.” Priya Khurana giggled, descending down a winding staircase in a pink Barbie top and beige leggings, her hair secured in a bun. “God, I can’t believe you’re still the shy kid I met years ago in his mother’s boutique.”

She introduced herself with firm handshakes.

“I’m never ever gonna wash this hallowed hand.” Abhi whispered in Akhil’s ear.

“So, I understand you guys are after HP4 and LOTR. Manpreet told me all about your hunt. I’ve read the books. Good taste you have.” Priya’s validation had the boys beaming.

“You have them, right?” Akhil asked.

“Yes and no.”

“Huh?”

“This bitch Kanika, my classmate, borrowed some of my books and moved to Canada. So the books are still mine but no longer mine.”

The boys sighed and consoled her by heaping curses on the girl overseas.

“So you got your own female bastard? We have ours too. Male in his twenties. Goes by Sam, an alias. We’ve been after him for months. Bastard got Akhil’s uncle thrashed real bad, then he moved to Patna. Although we’re not sure what hurt more—the fleeing or the thrashing. You’re rich. Your female bastard fleeing to Canada makes total sense.” Mukammal had to be elbowed into silence.

“So you can’t help?” Akhil came straight to business.

“I could. If you guys can afford the books, I can get them from Delhi next time I’m in Chapra. That would be in March. For Holi. Here, have some.” She pointed to a box of dry fruits on the table. They took a few, hesitantly.

The housekeeper, a lady in her forties, put down six glasses of orange sharbat from a tray and motioned Priya towards the living room.

“Well, hello boys! Getting cozy with my niece, eh? I suppose you’d be staying for high tea?” Priya’s aunt laughed at her joke. “Beena, fix me a sandwich, girl.” She called the house help.

“We’re good, auntie. Thanks for asking.” Priya turned towards the boys. “Sorry about that, guys. Where were we? The books, yes. See, you won’t find them anywhere in this town. You must have looked around. I, for sure, don’t mind getting them for you. Last I checked, the two titles shouldn’t be more than 1000 rupees together.”

“That’s too costly. We don’t have that much.” Mukammal had to be contained again.

“I didn’t ask for myself! You guys don’t want it, it’s alright with me. You can rent the Hindi-dubbed movies from that CD shop of yours. What’s the name? Mantu CD Centre.”

“No, no. We didn’t mean to offend you. 1000 rupees sounds good. We’ll get it to you before you return to Delhi.” Akhil signed the deal.

* * *

They left the bungalow on their bicycles, debating Akhil’s hasty decision on their way to the cricket ground.

“That aunt, acting all high and mighty! I suppose you’d be staying for high tea?” Abhi imitated the rich lady. “Like anyone with a shred of self-respect would say yes after that!”

“What’s ‘high tea’ anyway? They serve tea on a rooftop?” Karan tried grabbing his share of attention.

“Beena, fix me a sandwich, girl!” Abhi did another impression in his faux-female voice. “How do you fix a sandwich? With bandages?”

“I saw the girl, Beena or whatever, making the sandwiches, maybe for their ‘high tea.’ She was putting cucumber slices between bread. Then she cut the edges. Didn’t think twice before dropping off cucumber with the edges. And she didn’t even toast the slices. Man, is it even a sandwich if not stuffed with alu chokha and toasted in ghee? What kind of people are these?” Mukammal brought his ride to a sudden halt, executing a semi-circular skid that sent the rear wheel two feet in the air. The boys followed suit.

“Dude, you’re judging them for their food habits? They literally served us California almonds!” Manpreet came to his lady friend’s defence.

“You think a couple of nuts is generous? Hah!” Mukammal went on. “I did some math. These rich folk actually spend way less on guests than the middle class does.”

“Is that so? Go on then. Show us your research.” Manpreet prodded the fuming Mukammal.

“Think about it. They keep cashews, almonds, walnuts and what-not in a fancy box to deflate their guests’ ego. How many did you guys pick? Two, three, four? Not more than that, I bet. No self-respecting person would grab more than a few nuts. Half a kg or so would easily last weeks. Now compare this to what we, the middle class, serve our guests every day. All-milk-no-water chai, biscuits, namkeen, pakode, rasgullas. My ammi serves kebabs to family friends. Manpreet’s mom pours ghee like water. And all of our mothers insist that our guest not leave without lunch, or dinner. See my point now?

“Whoa! You’re some social scientist man!” Karan was impressed.

“I’m not kidding. Do the math yourself. And what on earth is a social scientist? The only scientists are scientist scientists.”

Despite Mukammal’s protests, Akhil had the boys pool their pocket money and cancel their library memberships.

“We can get new library cards later. These books are top priority right now.”

With the security deposit back in their pockets, they had enough for the books.

* * *

Their second visit to the big house saw Akhil hand over 1000 rupees to Priya Khurana who assured the boys that they would be spending their next spring in Hogwarts and summer in the Shire.

“Why do you trust her so much? Mukammal confronted Akhil on their way back. “What’s your hurry with people? Serving yourself up on a platter as soon as someone smiles and feigns affection.”

“Why don’t you trust her? Or anyone? Why do you always have to doubt everyone you meet?” Akhil fought back.

“You should have discussed with us before throwing away the money.”

“You mean I should have discussed it with you. What’s your problem with girls anyway? Is it because one treated you like shit and the other had you swim in a pool of shit?”

Mukammal grabbed Akhil’s shirt collar. He had to be apprehended by the boys. Akhil stared wide-eyed, his knees turning to jelly.

“You guys shouldn’t have let Mr. Smartass give his girlfriend the money.” Mukammal said resignedly.

“Then you should have said something then and there.” Akhil cried.

“Why? So you guys could rant and cry that I make a fool of you all wherever we go?”

They remained silent.

“What makes you so sure she won’t cheat us?” Mukammal stared Akhil in the eye.

“Why would she? We were nice to her.”

Author's Note: The story is based on scenes from the author’s childhood. The author has not read the fourth Harry Potter book and The Lord of the Rings to date.

This story first appeared in print in The Brussels Review.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.