I’d asked him to come at 8:40 but he always turned up at 8:30, and rang me to tell me he’d arrived though I’d told him he didn’t need to. I always planned to leave at 8:40 but it was generally 8:43 before I hurried downstairs. He was a careful driver: he slowed almost to a halt for speedbumps, and when he saw an old woman crossing, he slowed down and didn’t even honk. I appreciated this. But sometimes it was 8:45 when I came down, and then I wanted him to rush. But, caught between safety and the need to be on time for biometric sign-in, I stayed silent. He’d drive faster, but not too fast. I was grateful. It’s wonderful when people understand you wordlessly.

One day when I came down he wasn’t there. I rang him. No answer. I hailed an auto from the autostand down the road. Later he told me he’d been delayed. I told him he should’ve rung me, and that naturally I’d deduct the fare I’d paid that morning from his monthly fare. He said he had turned up eventually, then said “Okay, madam.” He was the softest-spoken autorickshaw-driver I’d met.

When I’d hired him, I’d asked him how much he wanted per month. He had several similar engagements, and he’d been driving autos for twenty years, so he’d know. Sitting on his driverseat, grasping the bikelike handles, his wide face cheerful under curly black hair, he’d merely looked away and mused, “Mmm.” When I insisted on a reply he said, “Madam, you decide.”

“Rs.1,500?” I’d suggested. That was about 10% more than the sum of the daily fares I’d have paid to drivers hailed ad hoc.

He hmmd again, his face looking troubled. Finally he said, “Madam, you sit now, later we can decide.”

I hadn’t wanted to leave the payment question hanging, but now I shelved it. It was convenient not having to walk to the autostand in the morning rush so, I decided, even if he wanted Rs.1600, that might be fine.

But when it was time to pay him at month’s end, I paid him Rs.1,500 and he accepted, though I could see he wasn’t happy. He never said anything, and he always showed up, so I stayed silent. He hadn’t a long distance to drive to my place, and our journey was short, and if he wanted to come ten minutes before the stipulated time, that was his lookout, and if he wouldn’t tell me how much he wanted, ditto. He kept coming. It was very convenient: I could pay him once a month instead of fiddling with cash or Google Pay with a new driver every day.

One morning his auto was there but he wasn’t. I rang him. No answer. I waited, asked the security guards if they’d seen him, and stalked off towards the autostand. He caught up with me en route, apologising profusely from his auto, saying he’d gone to the bathroom. I got in but I didn’t say, ‘It’s fine,’ and I didn’t ask ‘Why don’t you answer your phone?’ because I never answered mine either.

Another morning neither he nor his auto was there. I rang; no answer; I rushed to the autostand. That afternoon he sent me a voice message saying his leg was troubling him. I hadn’t noticed anything wrong with his leg, not that I’d been looking. He said he’d try to come next day. I began a list of how many days he’d missed.

Next day he didn’t come. I didn’t bother ringing him.

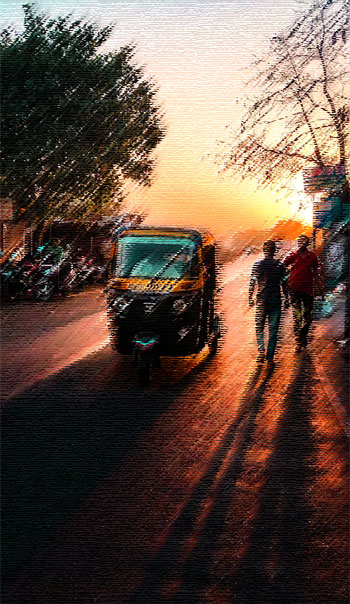

I got used to taking an auto from the stand. Often my driver was one particular raisin of a man, browned and wrinkled, whom I generally found sipping his tiny glass of tea at the tea-cum-stale-cake shop where autorickshaw drivers congregated. Paan spittle the colour of half-digested blood streaked the pavement and I had to manoeuvre delicately into the rickshaw. Cigarettes, paan, and tea were the drugs on which the drivers subsisted.

I had to leave home three minutes earlier to walk to the autostand, or, increasingly, towards the autostand to find the old man en route. At first he wasn’t always there: he was out ferrying schoolchildren or on short-haul Ola rides. But soon I began finding him always outside the teashop, recognising first his navy-blue windcheater and then his licenseplate.

As long as he was there, no other autorickshaw driver else offered to drive me. If he didn’t see me coming but the others did, they’d nudge him. He’d look up and hold up his teaglass, and I’d nod. He always finished his tea fast while I sat in his auto waiting.

The middle-aged autorickshaw driver rang me one day to say his leg had recovered from whatever he’d had and he could come again. I declined.

While I’d had him, I’d overestimated the trouble of walking to the autostand. Now that I didn’t have him, I couldn’t imagine waiting every morning for him to appear, wondering if I should wait for him, try his number, or rush to the autostand. The teashop was two minutes away, and it was less expensive this way. Besides, nobody had to wait for anyone: if the old man and I were in the same place simultaneously, then we had a deal, and drove off wordlessly. I wasn’t obliged to ring anyone if I was taking a holiday, and he wasn’t obliged to avoid my calls for reasons unknown.

I never looked back to when I’d engaged an autorickshaw driver by the month – except on the rare days when the old man wasn’t at the teashop. Then I had to proceed to the autostand. Sometimes there were no autos waiting. I waited for one to appear, consulting my watch ceaselessly, because I always cut the time fine.

The problem was if no autorickshaw drivers appeared, or if they demanded an excessive fare, or drove recklessly. Only then did I miss my curly-haired, soft-spoken, punctual, unreliable regular.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.