Kip steers my car around the curve of the gravel road, and follows the Sheriff's Department vehicle up a small rise. Pebbles kick up and ping off the underside of the car. Fog grays the sky and blows away from the Pacific. Its cold tendrils wisp around sturdy trees, grown bent by the unrelenting ocean breezes.

"It'll be cold out there," I say. I am not complaining. We have driven over two hundred miles from our home in Shasta County where the weather is busy breaking heat records. The thermometer outside a local bank read 120 degrees when we headed out of town, west toward the ocean and Humboldt County.

Humboldt County is known for its fog, logging controversies and acres of illegal marijuana plants. I remember a story a few years ago about an environmental activist who had camped out in the top of a huge, old growth redwood tree for months and months in order to save it from logging. I tell Kip the story.

"She named the tree Luna," I remember.

We laugh. "People do the strangest things," I say.

I turn my head to gaze out at the ocean. What would cause someone to drive sixteen hours through the night to a place they had never been, park their car, and disappear? According to the Humboldt County sheriff's department our subject, a 21 year old male, had done just that. His car had been discovered by locals, unlocked and loaded as if for a spontaneous road trip. He had told his boss at work he would see him on Monday, bought CDs and a new stereo system and then apparently climbed into his car and made the long trip from his home in Spokane, Washington to the California coast, alone and nonstop. Deputies had discovered items belonging to him on top of a cliff where rock and land slides happen almost daily. Locals recalled seeing the young man sitting out there almost a week before. He seemed to have disappeared off the face of the earth without a trace.

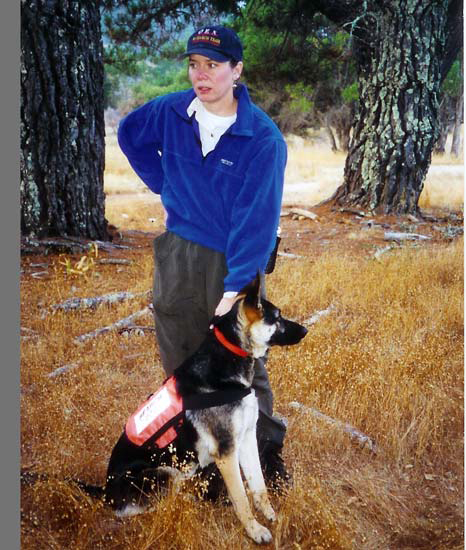

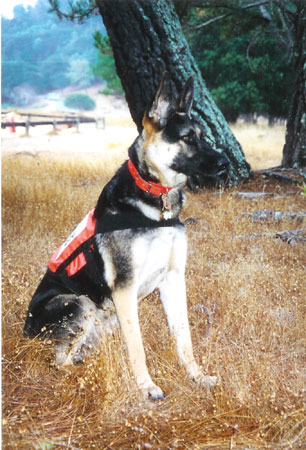

We pass an abandoned Naval base. Chain link and barbed wire seal its grounds off from the curious. Search base is just beyond this facility - a gravel parking lot at the end of the road. Kip kills the engine and we climb out of the car. I open the tailgate and pull out my search pack, checking to make sure everything I need is there. I add a Sam splint and some duct tape after glancing at the uneven terrain we will be searching. Kip packs extra water and snacks. Inside my car, my German Shepherd Caribou whines with nervous energy. She recognizes this routine and is eager to get started. I slip her shabrack, a bright orange Search Dog vest, over her head and secure the velcro straps. Around her neck, I fasten an orange collar with a bell. I hoist my fanny pack into place and strap my radio pack to my chest. I click the talk button on my radio to check that it is working and on the correct frequency. The answering click on a deputy's radio tells me we are all set.

"Ready?" he asks.

I nod.

My assignment looks daunting.

"We believe he went out this deer trail and made his way down the cliff side to where we found his belongings." The deputy points into a thick tangle of brambles and brush. I stifle the urge to ask him if he is kidding. "As you make your way down there, be careful. The ground here is unstable." This seems to be a huge understatement.

I glance down at Caribou, sitting calmly at my side, and wonder if this is a safe situation for her. She looks up at me and wags her tail, ears forward, eyes bright with anticipation. I make the decision to attach a long line to her collar. If she falls, I want to be able to stop her from sliding into the sea. My heart thuds against my ribs and I take a long, slow breath.

"Are you ready?" I say to my dog.

She bounces around me, tongue lolling, tail wagging furiously.

"Okay," I say, "Go search."

Caribou turns away from me and plunges into the brush, heedless of the thistles that scratch her sides. I give her fifteen feet of line and move out after her. Kip and a deputy follow close behind.

The ground almost immediately begins to descend. Over Caribou's head I strain to make out the slope, but the brush blocks my view. I worry that we may be going straight off a cliff.

"Wait," I say. Caribou stops and looks back at me. "How quickly do we get to the cliff edge?" I turn and ask the deputy.

"I've only been down here once," he says. "Just go slow."

His answer gives me no confidence. I tighten up on the line and give Caribou a mere five feet of play.

"Okay," I say. Caribou lurches forward again, crashing through the undergrowth with a confidence I don't feel. Brambles scratch my cheeks and grab at my legs. Now and then, Caribou hesitates, looks back at me questioning and I urge her forward. She goes, trusting that I will not put her in harm's way. Finally, when I am almost ready to turn back in frustration, the bushes recede and in front of us lies the Pacific ocean. Beneath the foggy skies, it looks uninviting and dangerous. Huge waves whirl and crash. White caps shatter the black surface. Just in front of us, the ground crumbles away to a slide area. We stop and regroup, plan how we will navigate this challenge. I turn to talk to Kip and in doing so, loosen up on Caribou's long line. Almost immediately, she leaps forward, slips ten feet and jumps from solid ground into the slide. Miraculously, she lands without incident, stops and looks back at me as if to say, Come on, mom, that was no problem. I shake my head.

"I have no idea what she was thinking just then," I say to Kip.

There is no way I can haul my eighty-five pound dog back up to us. We have to follow her. I inch over the edge and test the slide before stepping out onto the muddy surface. My boots slip. My breath catches in my throat. Ten minutes later, we are on the other side and on sturdier ground which lies mostly hidden beneath short scrub brush. The area is crisscrossed with crevasses. Rock piles dot the earth showing us where the ground has given way and slid closer to the sea. Caribou strains at the line and stares at me with impatience.

"That's where we found his stuff," the deputy says. He indicates a point which hangs over the cliff face. Red flagging tape flutters in the breeze.

I scan ahead of us, picking out a path around the slides and crevasses where it might be safe to walk. I re-deploy Caribou, giving her twenty feet of line. The scrub brush hides thick mud and steep drop offs. More than once I sink into unstable earth up to my shins. Caribou's tan underside has turned a deep, rich brown from the mud. Her tongue lolls and her lips curve into what can only be described as a smile. She loves this.

When we reach the red flagging tape, we stop again. I am careful not to get too close to the edge where the ground drops almost straight down along a jagged cliff. A recent slide here has made the footing slippery. I shake my head, glance at Kip and our eyes meet for a second. I know he is thinking the same thing as me. It would be easy for someone to lose their balance here, get too close to the edge, slip into the sea. It is low tide now and below us is a short, sandy beach.

"Was it low tide on Saturday when he was last seen here?"

The deputy shakes his head. "High tide." "And is there any beach at high tide?"

Again, the deputy shakes his head. "The surf comes right up to the cliff face. Strong undertow here, too. Even at low tide, if you wade into the water it drops off pretty quick and the riptides can suck you out."

"I'd like to get down to the beach," I say. I want to check the slides from below and look for articles that may have washed up and gotten caught in the rocks.

Getting to the beach is no easy trick. We backtrack and then slip and skid down a muddy embankment and over a pile of rocks. I ask about the tides in the area.

"Do they move north or south?"

The deputy doesn't know. I decide to work south of the place our subject was last seen for about 100 yards, and then head back north about two tenths of a mile to a parking area. I unhook the long line and allow Caribou the freedom to work off lead. She stretches out her long legs and gallops down the beach, checking shallow rock caves and nosing the base of slides. I imagine the sand feels good beneath her toes. My eyes scan the cliff base looking for anything that might be evidence of our subject. The gray rocks march away down the beach, uniformly bleak.

The beach yields no information pertinent to the search. By the time we reach the parking lot my calf muscles are burning and I am tired of slogging through heavy sand. We take a break at the parking lot and strategize.

We have covered the base of the cliffs along the beach. Above the cliffs the ground rolls upward, covered by thick brush and trees. A huge ravine sits just north of the place last seen and cuts through the earth all the way to the road, running east-west. It is possible that our subject might have attempted to return to his vehicle by walking north before ascending the hillside. If he had done this there would have been many opportunities for an accident, including falling into the ravine.

We decide that the best search strategy is to follow a deer trail which parallels the road and climbs along the ridge above the beach. This strategy will take advantage of the northeast breeze and also put Caribou at the best advantage to scent a human who might be located just below the ridge line. What I am envisioning is a hasty search of the area; a quick pass along an easy trail looking for any interest from my dog.

The walk along the deer trail is relaxing. Behind me, Kip and the deputy carry on a casual conversation. I watch my dog, looking for any signs that she is picking up human scent. Occasionally, I direct her with a raised arm down a slope or into a thick tangle of bushes. She moves as if on a guide wire attached to my arm, muscles bunching as she presses forward to check out an area. We cross behind the military facility, walking through tall grasses that bend in the wind, and end up in a high meadow just north of the ravine. Caribou's ears tip forward, her nose rises in the breeze and she moves away from me. I tense. Stop. Watch her move. Here is interest, the dog's indication that she has picked up human scent. Caribou weaves side to side through the meadow which slopes to the ravine. Then she stops, looks back at me. I test my wind with a small puff bottle of blue chalk. Northeast. Across the ravine I can hear the voices from other searchers congregating at search base. Caribou is a non-scent discriminating dog. She is trained to find any human in the area. The interest I saw might be due to scent blowing across the ravine from search base. But, I don't want to leave any stone unturned, and the ravine will need to be searched.

"Lets go back to base. I want to give my dog a rest and then come back here to check this area out more thoroughly," I say.

"Did your dog alert?" The deputy asks.

"No, but she looked interested. I think it's worth coming back and rechecking."

When we get back to search base, I notice a car with Idaho plates. A deputy stands with a group of people talking and I know immediately that this is the family. While they are talking, the deputy points down the hill. He gestures toward the cliff face. A man, who I assume is the father, turns away and rubs a hand across his eyes. Anguish is etched on his face and his eyes are red-rimmed. A knot finds its way into my belly. Our subject has just been personalized and the weight of our job loads my shoulders and tightens my throat.

Caribou rests for forty-five minutes. She lays in my car with her huge head resting on dirty paws. She dozes. But as soon as I say "Are you ready?" She is alert, ears up, eyes bright.

We return to the ravine. Its sides dip straight down and disappear in the foliage. There is no way to tell how deep it runs. Kip and I walk along the edge of the ravine and give Caribou the freedom to range as she pleases. We work our way down the hillside, skirting the ravine, until we eventually find the bottom. A muddy stream runs down toward the ocean, hidden mostly in a tangle of vines and brush. Caribou noses about with enthusiasm, but shows none of her previous interest. We try to work our way up the ravine, but our efforts seem fruitless in light of the thick vegetation. Sweat drips down my cheeks and mosquitoes dive bomb me, finding their mark in the soft flesh of my neck.

"He's not here. We're wasting our time," I say.

Kip agrees. The air here is wet with humidity and fog. Human scent would pool here, be overwhelming to a dog. Our subject has been missing for a week. If he were here, we would know it and Caribou would be frenzied with his scent.

We have done our job and I am confident that there is no one lying injured or dead in the ravine.

We head back to base camp. The car with Idaho plates crunches in the gravel and passes us along the road. The driver, the father, raises a hand in acknowledgement and I return the gesture. His face is obscured by the glass of the window. I can't make out the faces of the others inside the car, but I feel them. I feel their eyes watching us as the car rumbles past, a fine sheen of dust blowing up from under the wheels. Kip lays a hand between my shoulder blades for a moment and I am grateful that he is here with me. I look up at him.

"I wish we could have found him," I say.

"I don't think he was here to be found."

Behind us, the sound of the car from Idaho fades and is replaced by the crash of the waves far below on the cliffs.

EPILOGUE:

Two weeks later, we were informed through the Humboldt County Sheriff's Department that the young man we were searching for was found some two miles down the coast, washed up on the beach. He apparently fell to his death from the point on the cliff where his personal items were located.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.