The Piker Press recently caught up with the noted ornithologist Bernie Pilarski at his home in Ripon California where he graciously consented to an interview. Seated in a lawn chair next to a fish pond in which a dozen or so good sized gold fish swam lazily about, Bernie answered our questions.

Piker Press: Doctor, thank you for taking the time from your busy schedule to talk with us.

Bernie: (laughs) Not at all, glad to do it, but it's not "Doctor." Nope, don't have that kind of degree.

PP: Oh, sorry. Professor then.

Bernie: (laughs again) Nor professor. No one's offered any position to me, and can't say that I'd take it even if it was to be offered.

PP: Gosh, I'm sorry. Talk about getting off on the wrong foot. How shall I address you?

Bernie: Bernie would be fine. Mr.Pilarski would be okay. I never much held to that "Mr. Pilarski was my father's name" crap. That's nothing but the Peter Pan Principle with names: 'I don't ever want to grow up, so I refuse to accept an adult title.' So you can call me Mr.Pilarski if you like. I don't mind growing up.

PP: Well, then, Bernie ...

Bernie: There you go, that's right. Out of the lederhosen and into the fire, eh?

PP: Yes, well, the first thing our readers would want to know is where have you been? It's been quite some time since we've seen any new work from you in your Birds of Ripon series.

Bernie: Legitimate question, and I have a answer. As you may know, I consider myself nothing if not an ornithologist. It is my passion and my life. But the truth of the matter is that ornithology simply doesn't pay the bills. It's not like the Golden Era of ornithology when we were held in esteem and sat on the councils of men, a time when the proper description of a wren or a tit could start or stop a war.

PP: Tit?

Bernie: Of course! It is well known that it was the Roman imperial ornithologist Curius Ahala's description of Cleopatra's tit that drove Antony to Egypt to see it first hand.

PP: Oh, really?

Bernie: And by all accounts, it was a magnificent bird, a large Great Tit, the Parus major. Black head, white cheeks, and a necklace of black that trails down its yellow front. Here, this is a drawing of a fabulous pair of tits I saw, of all places, in a bar in Istanbul. People still flock to see them. Marc Antony recognized the potential money these birds could bring in exotic bird shows in Rome and told Cleopatra that with birds like hers, she wouldn't need to work another day in her life.

PP: (Snork)

Bernie: Mark Antony divorced his wife Octavia and married Cleopatra in order to personally handle her birds in the Roman markets. Business went well, and soon her tits could be seen everywhere in Rome. As her wealth grew, so did her fame, and soon she was the Queen of the Nile. But Antony ran afoul of Caesar when, in order to fill the ever-increasing orders from Rome, he began substituting crows that had been painted to look like a Great Tit. One of these doctored birds made its way to Caesar's chambers. Gasps of horror came from the courtesans as Caesar emerged from his chambers with yellow lips and a sheepish looking, disheveled crow with a smudged yellow front and smeared white cheeks.

PP: You're joking, right?

Bernie: Now see? That's where we've come. Today, the ornithologist no longer carries the weight that he once did. And the money stream has dried up. Those of us in the field, like myself, have to take "day jobs" to pay the bills. Fortunately, or unfortunately as you care to see it, my "day job" has been consuming most of my time, and my work in ornithology has become, how shall we say it, more measured.

PP: Ah.

Bernie: Yet as you can see, there is so much that can be learned from ornithology. That is why it remains my passion.

PP: Has it always been your passion?

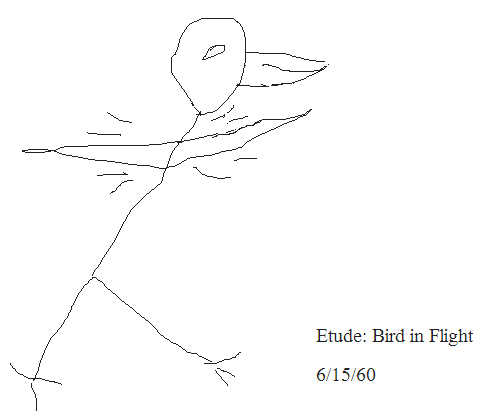

Bernie: Heavens, yes! Since I was a young child. I still have the first drawing I ever made of a bird. Care to see it?

PP: My, it's not quite as detailed as your later works, is it?

Bernie: It is an etude, a study piece on the dynamics of flight.

PP: Etude?

Bernie: I can still remember the instructions.

"Etude, don't make it hard

take a small bird and draw just the bones,

Remember, you don't need to draw the skin

And then you need at most just two tones.

PP and Bernie:

Nah, nah, nah na-na-na nah,

Na-na-na nah, eh-tood...

Nah, nah, nah na-na-na nah,

Na-na-na nah, eh-tood.

Bernie: TOODIE, TOODIE, TOODIE.

PP and Bernie:

Nah, nah, nah na-na-na nah,

Na-na-na nah, eh-tood...

Nah, nah, nah na-na-na nah,

Na-na-na nah, eh-tood.

Bernie has been much consumed with his day job and with his new novel Mr. Cutter's Problem. He provided us with a promise of more ornithological insights and this excerpt from the new novel:

Chapter Two

When death came to Fr. John Stanko, it was no surprise, nor was it unwelcome. He was found slumped in his desk chair in his office in the rectory. A heart attack, apparently, but the truth of it was that his heart had broken before it was damaged physically, and it was the pain from that break that killed John. He had gone to his office, sat down, and died, because he could not figure out what else to do. He had been a priest for more than twenty years, and had never wanted to be anything else, but on the cold December morning of his death, his heart was heavy, too heavy, and tears filled his eyes even as he made his way to the office from the church where he had been praying. He closed his office door, walked to his desk, and sat down. He let his arms drop and hang on either side of the chair, turned his face toward heaven and wept like he not done since he was a child, but there was no relief from his pain. As he wept, it felt as though his throat opened, slit to form a gaping hole from which he began to drain from his body. The sensation was sudden and rapid, a breach.

John had a momentary flash of memory. He was a child, at the seashore where a storm had eroded the beach and left a wall of sand about six feet high at the water's edge. He had followed a sand crab as it scurried away from him and disappeared over the eroded precipice. He stood atop the sand, toes at the edge, looking down the freshly exposed wall. The hairs on his neck stood up as he saw dozens of the sand crabs at work on repairs to their habitat. One crab was a curiosity, but dozens seemed a threat, and John was beginning to back away when the sand beneath him gave way, sending him sliding down into the midst of danger.

When his throat opened, it felt very much like that sand giving way. His sight and hearing rapidly contracted until he was aware only of being inside his head. His presence was being drained from the world, all sensation retreating first to the brain, then being sucked out of his body through the hole in his throat. He clung to the inside of his skull, not with his fingers, but more as if attached, like meat attached to skin, so that as he was being drawn down, it was as if he was being torn away from his body -- the slimy feel of a grape being expelled from its skin.

And then it was over, and John Stanko found himself adrift in darkness. There was no sight, no sound, no hot, no cold. There was no up or down. There was no passing of time.

Death, it is said, occurs at the point at which the body fails to respond to the will of the soul. Life goes on, inextinguishable, but the body tires and eventually fails. This was a truth, the stock and trade of John's life as a priest. It was for this moment that he had prepared people, the moment when faith ends and the person, stripped to an irreducible element, confronts the inextricable relationship of creature and creator. This is a moment of unimaginable joy, Fr. Stanko had preached, the moment when the soul, unencumbered by the flesh, becomes pure prayer -- a free and complete response to God. Wrapped in God's love, the soul is then taken to its reward.

This is what John believed, and indeed, in the darkness, there was a presence, a familiar presence, warm and inviting. The stage was set for John to pray, and yet, there was only an anguished cry -- "Kyrie, eleison!" Lord, have mercy.

Unencumbered by a body confined to time and space, his spirit lay exposed. His thoughts were his countenance, his actions his heart. The evidence of his baptism shown on his soul as a band of brilliant white light, confirmation a band of red, and his ordination a golden aura streaming out in all directions. In the darkness, there was a reckoning, an accounting of the love John Stanko had for his creator -- "Christe, eleison!" Christ, have mercy.

The disembodied spirit is vulnerable. It has always relied on senses of the body to perceive its world. What it had learned, it learned from touching, tasting, feeling and hearing. What it was able to express, it did in sound and light and the forming of the elements of the earth. Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum. Et vitam ventura saeculi. "I await the resurrection of the dead, and life in the world to come." The condition and destiny of the human soul is to be the animating force of a physical being, and so it is that the transition from this world to the next, from this life to the next, the time when the soul must exist without the benefit of a body, can be a time of stress. Death, it seems, can be disorienting, and the soul must cast about in an attempt to interpret what it is experiencing.

Consider da Vinci's Mona Lisa. A person can look at the painting, where the artist has skillfully arranged color and shapes, to see an image of a young woman. There is of course no woman there, only the artist's careful instruction on how to go about seeing what he saw -- an idea incarnated in oil, the oil in turn engendering an idea.

Consider Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon. The five stark, nude figures are a jarring departure from Mona Lisa. Where da Vinci meticulously controls the medium to lead the observer to a specific experience of a specific individual, Picasso tosses onto the canvas only the general outlines of the human form and demands that the observer participate in the completion of the image. A simple line becomes a mouth, two lines a nose, an oddly shaded square suggests a breast. The painting is unsettling, perhaps because it seems so undisciplined and chaotic, but more likely because it exposes the observer. The very vagary of the image requires a larger and more intimate investment from the observer to see the women of Avignon. The idea engendered from the oil is less predictable, an idea as much the observer's as the artist's.

What now happens if there is no medium? What does a soul do when it is given to know an idea directly? What does it do when it is bereft of its senses? Fr. Stanko had hundreds of times in his ministry, with censer in hand, circled the pall draped coffin of one of the faithful and said:

O God, Whose attribute it is always to have mercy and to spare, we humbly present our prayers to Thee for the souls of Thy servants which Thou has this day called out of this world, beseeching Thee not to deliver them into the hands of the enemy, nor to forget them for ever, but to command Thy holy angels to receive them, and to bear them into paradise; that as they have believed and hoped in Thee they may be delivered from the pains of hell and inherit eternal life through Christ our Lord. Amen.

He believed, sincerely and literally, that God would send his angels to usher the soul to its proper place. He had imaged the soul of the departed to be grappling with a scene more distantly removed from Picasso than Picasso from da Vinci. Just as a young child frantically tries to interpret the protean shadows of his darkened bedroom, sometimes seeing monsters and sometimes fairies, the soul would cast about for familiar images to help it understand. An unscrupulous entity may trick the soul into seeing beauty where there is none, perhaps as Picasso's prostitutes of Avignon might appear to some as innocent and pure. But it would be the angels of God who would shepherd the soul along, easing the transition.

And how would they appear? As young men, comely in appearance. Or innocent children. With wings, or without. In human form or a bit more ethereal. It could be any of these, any image that helps the reeling soul to understand.

In all the time Fr. Stanko contemplated this process, in all the time he consoled the grieving with the comforting images of warm welcomes and angelic escorts, he had always assumed that, except for the damned, the soul would be eager to reach its destination. Yet as much as the light of heaven that he saw was gloriously beautiful, it terrified him; and while his angelic escort, the most fair women he had ever encountered, bid him to follow, he did all that he could to resist. Kyrie, eleison, he cried. Kyrie, eleison.

There was a soul still in the world that was in peril of being lost -- a woman that John had failed, both as a priest and a man. It was this failure that killed John and so embittered the woman that she refused God's grace. He loved her, and that love threatened to damn them both to hell. He could not die and leave her behind. But God is merciful. God, it seems, saw that his servant John's love of the soul in peril was nearly as passionate as his own, and he granted John's prayer. John would be allowed to return, in a fashion, and to try to make amends.

There was no apparent reason John's death should be related to Malcolm Cutter. Maybe it was because John died on the day Malcolm was conceived. Or maybe Malcolm's near death experience on the operating table happened at just the right moment. Or perhaps John's and Malcolm's names coincidently appeared next to each other on some angelic to-do list. In the mysterious ways of God, Fr. John Stanko was about to become Mr. Cutter's problem.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.