In the back country, among the hills and valleys covered with dense forests, the landscape seemed to change with every bike ride I rode through it. Streams and waterfalls suddenly appeared where they hadn't been the year before, and groves of quaking elms sprouted up amidst the pine and maple trees as if overnight. Dirt roads and naturally made paths, formed by seasonal weather and wildlife, appeared and vanished with regularity, constantly challenging my sense of direction and memory. Taking the bike down from the wall of the shed that sat apart from the cabin we returned to each spring, which included my yearly bike ride in the wilderness, became a ritual re-enacted for ten consecutive years. Part of the repeated scenario was Helen standing on the cabin porch, waving and telling me to be careful as I left the yard and cycled off, beginning on the road that led to the cabin and then veering off into the woods on the first dirt road or path that interested me.

On the morning of the eleventh year of the bike ride the sky was cloudy and dark. The scent of rain was in the air accompanied by moisture that wet my hair and skin within minutes of walking out of the cabin and to the shed. Along with the bike I took from the wall a nylon poncho and a wide-brimmed waterproof hat that I usually wore only when going fishing. I left the shed and at the cabin porch put on the small backpack that contained my cellphone as well as a thermos of coffee and four turkey sandwiches wrapped in cellophane that Helen made for me. I shoved the poncho into the backpack and rested the hat on my balding head. Helen came out just as I sat on the bike.

"It looks like a possible thunderstorm is brewing," she said, glancing up at the sky. "Can't your ride wait a day or two?"

"Nature beckons," I replied with mock bravado. "I'll be home late."

"Please be careful," she said.

I put my feet on the pedals, and with her waving, I rode off.

Finding the first turn off from the main road I wanted to take was done mostly by intuition; if it felt like the road or path I should take, I took it. I could always take a different route once I had ridden a good distance into the woods, and often did, but the onset of each trip was wrapped up in mystique of my own creation.

A newly created narrow path that cut between tall cedar pines was where I turned onto. The surface was surprisingly smooth, as if paved by mechanical means, barely challenging the capabilities of my mountain bike. Avoiding the branches that hung down over and across the path presented the only difficulty. I rode for nearly an hour without a problem. Needing more challenge and scenery that was more than pine trees, I turned onto another path, and then onto an unpaved road that was wide enough for a single motor vehicle to drive on, but it began, or ended, inexplicably in the middle of the woods. I marked the intersection of the path and the road by tying on a tree branch a yellow band, one of many that I kept in a pouch tied to the middle bar of the bike. They served as the bread crumbs that I could always follow back to the cabin.

An hour later, while riding on the road lined with densely crowded maple trees, the rain began to fall. I took the poncho from my backpack and put it on and tightened the chin strap of the hat. Fifteen minutes later I came upon open acreage of what looked like grazing land for cattle or sheep that was surrounded by wood rail fencing. It was the first time in the many rides I had taken on the many roads and paths where something other than a vacation cabin had appeared anywhere on the forested land. A short while later, with my tires slogged down by mud, I came upon a gate that separated the road from an unpaved broad path that led to a barn, several fenced-in animal pens, and a small house. A steady stream of wispy smoke rose from the chimney. At the gate standing in the rain was a young boy whose skin was as pale as chalk. His bare feet were caked with mud and his pants legs were rolled up to just below his knees. He held a wild rabbit in his arms. Seeing me, his eyes expanded to the size of hockey pucks.

"What are you?" he stammered, clutching the rabbit to his thin chest. He and the rabbit were soaked.

It seemed like such an odd question. He didn't ask who I was, but what I was.

"I'm nobody special, just your everyday run-of-the-mill man " I replied with a chuckle. "My name is Mike. What's yours?"

"I like the name allosaurus," he said, "but my real name is Wallace."

"Nice to meet you, Wallace," I said. "Allosaurus, the dinosaur?"

"There any other kind of allosaurus?"

He had me. I quickly changed subjects."Do you live here?" I pointed at the house.

He nodded.

"I haven't seen any other places around here," I said. "What kind of farm is this?"

"It's a dinosaur farm," the boy replied.

A man in denim overalls appeared on the porch of the house. "Wallace, who's out there with you," he called out.

Wallace turned and looked at the man. "He says he's a mill man, Pa."

"Bring the man up to the house," Pa, said. "But let that rabbit go free first. It don't want you carryin' it around all day."

"Yes, Pa," Wallace replied. He set the rabbit down and patted its tail. "Get on with you," he said. The rabbit hopped off and disappeared in the tall grass on the side of the driveway.

"Pa wants you to come to the house," he said. He unlatched the gate and swung it open. "That part of you?" He pointed at my bike.

"No, it's my bike, but it works better if I'm riding it on solid ground, like any other bike," I said.

"Bike," the boy muttered as if mulling the word over for the first time in his life.

I got off of the bike and pushed it along as I entered the path leading to the farm, waited until he closed the gate, and then followed him to the house. It was badly in need of a fresh coat of paint and the way some of the boards on the porch were buckled, showed the signs of general neglect that were apparent on the facade. There were poorly sculpted wooden dinosaurs nailed to the porch posts There were two floors. A window on the second floor was covered with piece of plywood.

"Your boy thought I was a dinosaur," I said with a gentle laugh to Pa as I leaned the bike against the porch and stepped up on the first step. "He didn't know my bike was a bike."

"He ain't ever seen a bike before," Pa said.

"But in school . . ."

Pa cut me off. "Wallace don't go to school and he ain't too bright. He knows two things, dinosaurs and wood carving," Pa said, "the two things he learned from his Ma before she passed away two years ago. A married couple who had a cabin a few miles from here attended her burial, but we ain't seen them or anyone else since, so he ain't had much acquaintance with things beyond our farm."

I glanced over at Wallace who was still standing in the rain, with a squirrel sitting on one shoulder. "How old is he?"

"He were born nine years ago."

"He's really pale," I said. "Is he okay?"

"He's fine. He's light complected like his Ma was." He opened the door and waved his hand inward. "Come in and dry yourself by the fire."

"Thanks." I leaned the bike against the porch and started up the steps, but before going in I glanced back to see Wallace eyeing the hump under my pouch, but thought it best to show him it was my backpack when we were in out of the rain. But as I went inside, Pa closed the door, leaving Wallace standing outside in the mud with the squirrel running up and down his extended arm.

Inside the house it was very warm. A small fire burned in a stone fireplace. All of the furniture looked hand crafted. On every available flat surface in the large room that looked to be a combination of living room and dining room stood dozens of Wallace's crudely made wood carved dinosaurs. I took off my hat, poncho and removed the backpack and sat everything on the floor next to a chair made of pine tree limbs and branches. "My name's Mike," I said as he put wood in the fire and poked at it with a long stick.

He turned his head and looked at me as if suddenly remembering I was there.

"Jacob," he said, "but ain't no one called me that in a long time. Wallace calls me Pa, of course, and so did my wife."

"How long you lived here?"

"All my life." Embers rose in the air above where he stirred. "You married and got kids?"

"I'm married. My wife is back at our cabin. We don't have any children." I heard the rumble of thunder and looked at the door. "Shouldn't Wallace come inside?"

"What for? He'd just want to go out again to spend time with the critters and dinosaurs." He placed the stick by the fireplace and sat in one of the three chairs in the room. "You can take your clothes off and hang 'em by the fire to dry if you want. Don't be scared. I ain't seen another body in a long time, male or female, other than Wallace's, but I ain't got any lustful thoughts about you."

"I'll just stand by the fire and dry myself that way, if that's okay?" I said, not comfortable with being naked with a man I'd just met in such an out-of-place location. It had the markings of a horror movie.

"Do what pleases you," he said.

I walked to the fireplace, turned and faced it. For several minutes, other than the crackling of the fire the only sound was that of the occasional thunder echoing over the surrounding hills. Lost for words, my mind buzzing with questions, I said nothing. He was silent for his own reasons, whatever they were. When the door opened and Wallace walked in, he had in his hands a basket of eggs.

"The pterosaurus laid a whole heap of eggs, Pa," he said. "I thought we might have some for lunch."

I looked at Jacob. "Pterosaurus?"

"Chickens," he said. "To Wallace anything with wings is either a pterosaurus, pteranodon or . . .I always forget the other one." He looked at Wallace.

"Pterodactyl," the boy said.

"Ah yeah, That one. You like eggs?" Jacob asked me.

"Sure. I have some turkey sandwiches that my wife made I'd be happy to share with you."

"Fix the eggs, boy," Jacob said. "We're about to have a real feast."

* * *

After lunch the talk of dinosaurs resulted in Wallace dragging out from under his bed a large book, The Big Book of Dinosaurs, which he proudly presented to me for my perusal.

"It's what his Ma used to teach the boy how to read," Jacob said. "It's the only book we got."

I sat at the table and flipped through the yellowed pages as Wallace examined my cellphone, dubious about my claim that people could talk to one another with it, especially since I had forgotten to recharge it the night before and the screen was black. He understood electricity because his Ma once talked about it, although their house didn't have it.

By the time I was ready to leave, my clothes had dried.

"Don't you want to see the farm?" Wallace asked, seeming to be excited at the prospect of showing me their dinosaurs. "That okay, Pa?" he asked, rising up and down on the balls of his dirty feet.

"Sure, but don't let the raptors get him," Pa said. He then looked at me. "Billy goats," he whispered.

I followed the boy out of the house and laid my things on the porch. The rain had stopped, leaving large puddles in the dirt and a balminess in the air. A haze hung over the fields beyond the house. We first walked to the barn where inside he pointed out the two horses and a donkey as being deinocherius, and showed the coop where he had retrieved the eggs from the pterosaurus. The chickens sat in their nests clucking to their chicks.

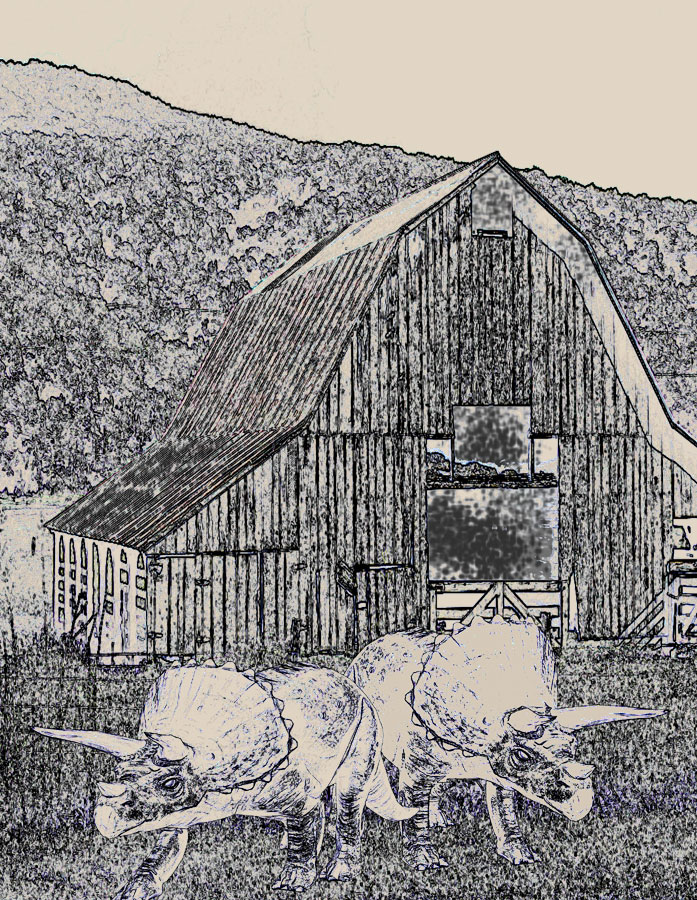

In the pig sty just outside the right side of the barn we watched four enteledonts wallowing in the mud. At the cow pen we watched several triceratops munching on a bale of grass.

Only the fields were left to see, I started toward them when Wallace grabbed my hand. "You can't go out there," he said. "The T-Rex will kill you even if you're with me. It ain't ever seen you before and might think you're goin' to hurt me."

I smiled, kindly. "I wouldn't want that to happen."

"Me neither," the boy said. "I hope you'll come back sometime. I'll introduce you to him then."

Walking back to the porch, we passed a large garden as we talked about my work, but it was apparent he understood nothing I said about accounting and had no real concept of what money was. Jacob was standing on the porch when we got there.

"How you like our farm?" he asked.

"It looks like you have everything you need to survive. But I would have liked to have seen the T-Rex," I said, winking.

"Yeah, it's something to see," he said with a chortle.

I said goodbye to him and with Wallace following behind, I walked my bike to the gate. He opened it for me and I went out to the road before getting onto the seat. I adjusted the chin strap on my hat, shifted the packed backpack on my back, and rode off, looking back to see Wallace standing at the gate, watching me go.

A quarter of a mile down the road I heard the loudest roar I had ever heard from any animal. Its menacing bellow seemed to fill the entire valley. I came to an abrupt stop and looked back, thinking I would get a glimpse of whatever produced such a loud noise. Seeing nothing I rode on, following the yellow bands all the way back to the turn off to the main road.

* * *

Helen was surprised when I said that I was going to take another ride out to that farm, saying nothing I had told her about it sounded normal. "Are you sure you want to get any more involved?"

"If you only met the boy, you'd understand my feelings," I said. "He believes his animals are dinosaurs."

With an understanding smile on her face, she waved as I rode away, heading for the same path I had taken before. I found that path, but not the same path I had turned onto from there, nor the road that led to the farm. I found new paths and different roads a few days later, and again the next year, but never found the farm again.

10/18/2021

09:49:39 PM