I'm going to tell you the story about the fate of Dickie Paponovitch. It's been years since all of this happened, but it still haunts me. I keep trying to understand it. I try not to let it be an obsession, but, so be it. I've seen the newspapers, spoken to the investigating reporters, Dickie's parents, Big Pat's mother, and of course the police.

My name is Joe. I lived just up the block from Dickie. We were friends. In fact, I was probably his only friend. Most of the guys I hung around with didn't like Dickie Paponovitch. That didn't bother me. One on one, he could be funny and had a wealth of knowledge about super heroes. Nevertheless, he was an easy target for ridicule, and he didn't handle that well. It seemed that in a group, he always managed to piss people off. If he could have been more generous, acted less entitled, I think it would have been different. Instead he would utilize his leverage, having supplied the necessary equipment to play whatever game we chose, to control the role he played and how the rules would best suit him. This drove everyone crazy, and I could never get Dickie to see why that was. If he didn't agree with someone, he left, taking his equipment with him. I'd try to get him to stay; but, no, he was going to participate on his terms or not at all. The game would be disrupted, and it didn't have to be that way. He couldn't get past his own anger, or was it pride? Maybe he was just insecure. I wanted him to be more like the rest of us. It seemed he was willing to sacrifice his happiness for whatever he got out of making us feel inferior.

The summer of our twelfth year, we were playing baseball. George, two years our senior and the de facto ruler of the playground, was fed up with Dickie. When Dickie decided to walk off the field in the middle of the third inning, George ran after him, and, without warning, threw a flying cross-body block across Dickie's back. Dickie fell to the ground with a frightening scream. I ran to Dickie and attempted to console him. George pushed me away. George gathered Dickie's ball, bat, and catcher's mitt and threw them at Dickie's feet.

"You want to go? Go! Don't come back." George shouted into Dickie's face, which was pale and streaked with tears, as he lay on the ground shocked, but not physically hurt.

Dickie slowly pulled himself up and collected his things. His head hung down, and he was unable to make eye contact with George or any of the rest of us, for that matter. He couldn't even look at me.

"Go! Go!" George commanded.

I'm sorry I didn't ask him to stay. Dickie went, and he never returned. We continued to play our games, without Dickie Paponovitch and his equipment. In fact, I saw and heard little of him from that time on until two years later.

It was late summer. The word around the neighborhood was that Dickie had run away. No notes were left. He didn't even take anything. His older brother, Steven, and Big Pat confirmed Dickie's mother's worst fear: Dickie had left. I had seen Dickie at the bus stop on the way to and from school. We never spoke, I felt badly for him, he seemed so alone, but I just assumed that was the way he wanted it. I could have tried to talk to him, but I didn't. Dickie was withdrawn. He seemed unapproachable, but that is no excuse for not trying to approach him. He preferred to hang out with Steven and Big Pat. We all noted that he acted even more arrogant and entitled when he was with them.

The first day that Dickie hadn't come home, his parents hadn't been concerned. When he didn't appear the second day, they started to worry. On the third day, they contacted the police and the news media and tried to promote a broad search, but the investigation into Dickie's whereabouts was not very intense. The police insisted that Dickie probably ran away and would try to contact them. There wasn't much to do but wait.

When questioned by the police, and reported in the newspapers, Steven and Big Pat said they had last seen Dickie walking north on Karacong Drive. He was angry. According to Steven, the three had been trying to decide how to pass the time of day. Steven and Big Pat wanted to head to the shopping mall to get something to eat. Dickie wanted to go to the high school to cruise the streets in order to show off Big Pat's car. The older two decided to fill their bellies rather than feed Dickie's ego. When Dickie got out of the car and threatened to go his own way, they didn't stop him.

They said Dickie was frustrated, angry, because he was unable to get his way. Pat said Dickie even picked up a stone and threw it at the car. The stone hit the car and dented the hood. Dickie took off down the road in a sprint, shouting, "Don't expect me home later, Steven."

I heard from Steven that Dickie often acted this way; and, although he didn't think Dickie was serious at the moment of his departure; when Dickie didn't come home at dark, he realized that he probably wasn't coming home.

Months passed, and Dickie failed to return or attempt to make contact with anyone. Steven appeared shaken by Dickie's absence. He'd grown sullen, and often stood apart from us at the bus stop each morning before school, not by exclusion, but by his own unwillingness to interact with us any longer. We were concerned and even began feeling sorry for Steven. One day, I saw George approach him.

"Hey, Steve, heard anything about Dickie? Is he still missing?" It was a cool, late autumn morning. The leaves were already off the trees.

"No. Nothing," Steven answered as he stood off to the side, withdrawn.

"Nothing?" George asked as if he hadn't heard.

Steven didn't answer.

"I haven't seen Big Pat around either. Have you?" George asked. He didn't hold any fondness for Big Pat. Older and bigger, Big Pat was a well-known bully and troublemaker.

Steven didn't answer.

"I heard he dropped out of school," Tom said.

"I heard he joined the Army," David interjected, having overheard George's question to Steven and Tom's response.

The bus arrived, and we boarded. Steven waited until David, Tom, and George sat before taking a seat as far as possible from them. Steven just hadn't been himself. Rumor had it that all he did was mope. He didn't go out, except to go to school. He just slept, and hardly ate. We assumed his behavior was out of concern for his brother. His parents told me that they took him to a psychologist, but he was as withdrawn with the doctor as he was with everyone else. As winter came, he sat in his room staring out of his window and watching the snow. He continued to go to school but his behavior remained without enthusiasm or feeling.

The snows were heavy that winter. With the spring thaw, the creek that meandered through the park by the playground overflowed its banks, scouring the flood plain. Twice daily, early morning, before school, and evening, after dinner, George ran his dog, Beau, a fox terrier, along the creek to the end of the park and into the adjacent woods. The path followed a narrow gorge that in colonial times was traversed by a stone dam, which tamed the creek and provided power to a powder mill, mainstay of the local economy. The dam had long since fallen, although remnants could still be seen poking through the dense brush, and the creek was allowed to meander through the gorge unimpeded.

As the water receded, George resumed his daily jaunts with Beau. He told me that once they reached the woods, he'd unleash Beau. As they ran along the stream, Beau would disappear into the brush to pursue a rabbit or muskrat he might encounter.

The weeds crackled as Beau darted through them. It was a bright day that spring, as they took their daily walk, Beau was several hundred feet ahead of George who jogged along the narrow path, but quickened his pace when he heard Beau barking and snarling wildly at something ahead.

"Beau, what have you got there, boy?" George said as he approached, proud of his dog's ability to flush out game.

Beau moved back and forth, body low to the ground, teeth bared, ears down, the hair across his back bristling. George approached cautiously.

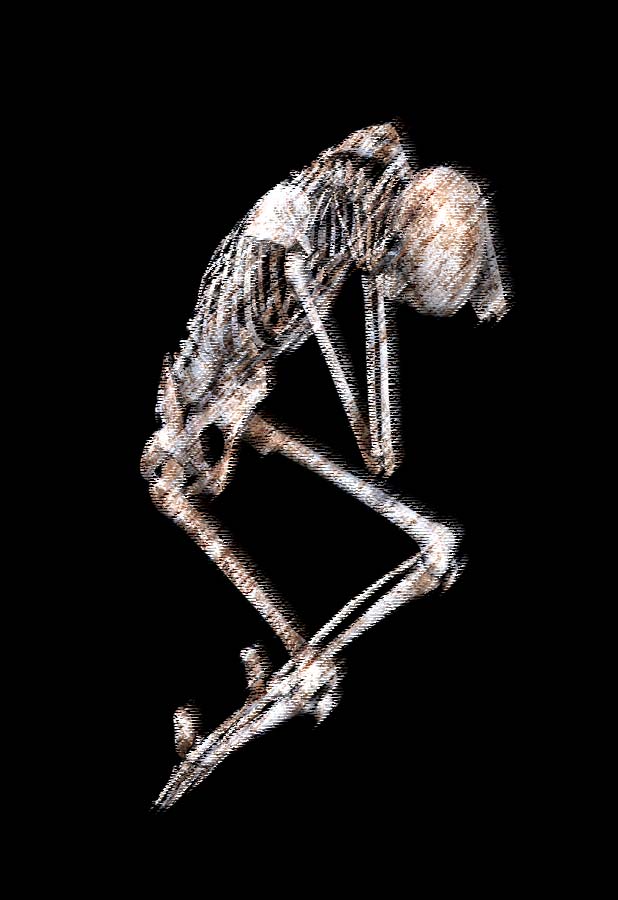

"Corner something?" George said as he came up behind the dog. Suddenly, George reared back and covered his face as a pheasant flew up in front of him. George stepped to the side reflexively, his right foot fell onto a sharp slippery stone recently uncovered by the creek's high waters, and down he went. He flexed his neck, taking the brunt of the fall with the small of his back. The soft ground cushioned the fall. George turned his head to the right as he attempted to rise and gasped as his hand touched another hand. He turned away and began to scramble to his feet as fast as he could. He rolled to the left and let out a long howl that steadily escalated in tenor and pitch to a shrill cry. There he beheld, face-to-face, the decomposed remains of a head. The eye was half out of its socket, and the other eye was missing. The lips retracted around the teeth in a sardonic smile. At first, George was frozen in horror, but then he scrambled back onto his feet and ran.

It didn't take the police long to identify the body revealed from its shallow, concealed grave by the probing tides of winter's thaw. It was Dickie Paponovitch. Steven was the next to buckle.

"But you were the last one to see him. You must know something. Try again, think," the detective said. Two hours passed. The detectives learned nothing new, but remained relentless in their questioning.

Steven paced in the small room as he had throughout the questioning. He was silent, no longer answering. He repeated the story again and again. The same story he and Big Pat had given from the beginning. Then he stopped pacing. He trembled with fear and sadness. It was over; he couldn't take the guilt any longer. He had to speak, but he feared Big Pat even more than the consequences of the truth.

"He said he'd kill me if I talked."

"Who said?"

"Big Pat."

"If you talked about what?"

"About what really happened to Dickie."

Steven took a deep breath. He had to talk. He felt compelled to be rid of the terrible burden, the guilt. He couldn't be silent any longer.

"It was an accident. Big Pat said he'd kill me." Steven's voice, much louder, trembled, a full octave above its normal level. "Don't let him hurt me."

"Who? Who's going to hurt you?"

"I already told you, Big Pat, Big Pat."

"Nobody is going to hurt you," the officer assured him.

Steven, ready for the long overdue catharsis that was to follow, began to sob. Silence had eaten at him these past months. Silence had eaten at his soul like a black cancer.

"Big Pat was driving his car. We were fooling around, just having fun. Suddenly, Big Pat made Dickie get out of the car." Steven closed his eyes. He could barely say it. "He, he was dead," he stammered. "We thought he was dead." He looked up at the policemen. "Big Pat said we couldn't tell anyone."

The officers sat back, questions raging through their minds, but they remained silent, willing to let the boy unburden his conscience. He was distraught, disheveled, his eyes wide, glazed over with distress.

"We were having fun. Big Pat just suddenly said, 'Get out!' He slammed on the brake causing the car to skid to a halt making us all jerk forward. Dickie shouted, 'What?! Me?!' He looked surprised. 'Who else?' Big Pat said with a very mean serious look on his face."

Steven continued, "Dickie hadn't done anything as far as I could see, and I wasn't sure if Big Pat was kidding or not. We were on Karacong drive, where there are woods on either side, and not traveled much at that time of the day. I asked if I should get out too."

Steven looked away from the police for a moment, took a big breath, put his face in his hands. He was no longer sobbing. He continued his tale.

"Big Pat said, 'You can stay. He goes.' Big Pat leaned forward, pointed his finger at Dickie, then slowly reached toward him until he touched Dickie's shoulder. He continued to push, forcing Dickie against the door. Dickie protested, but Big Pat never let up. Dickie opened the door, and Big Pat pushed him out. Big Pat was much older than Dickie and enjoyed pushing him around. I think he fell out of the car; Big Pat hit the accelerator, and the car lurched forward. Dickey rolled away from the car toward the shoulder of the road. Big Pat didn't go far, maybe a hundred feet. He screeched to a stop, put the car in reverse, and backed up to where he pushed Dickie out of the car. The tires squealed as he backed up, leaving black tread marks on the street. The tires squealed again as he hit the brakes, sliding to a stop where he dumped Dickie. 'Yo, Dickie. You can get back in the car,' Big Pat called. There was no answer, and no Dickie to be seen. We scanned the woods on either side of the road. Big Pat asked me if I saw him anywhere.

" 'I don't see him,' I said. I was still shaken by how Big Pat had been acting a few minutes before.

"'If he wants to play this kind of game, OK. OK,' Big Pat said. He seemed annoyed. You could always tell. His red hair was ruffled, and his freckled red face was flushed and even redder. 'If he can't take a joke ... well ...' He never finished the phrase. He just shifted the car into forward gear started to leave. There was a sudden yell off to the right, just ahead of us. It was Dickie. He had run from the cover of some bushes by the road and was charging at the car. He held a stick above his head. Big Pat stepped on the gas and attempt to speed by him. Dickie dove onto the hood as the car sped past him. He struggled to stay on as he swung the stick at the windshield. Unable to get much power, his blows failed to cause any damage. Big Pat steered the car from side to side as Dickie held onto the hood. Big Pat hit the brake, and as the car quickly came to a halt, Dickie flew off the hood and onto the street. I could see the small of his back hit first. The back of his head snapped down after, like a whip, down onto the hard street, with a dull pop, and then up again like a rubber ball before coming to rest on the hard asphalt.

" 'That should serve him,' Big Pat shouted with triumphant glee having succeeded in getting Dickie off the hood and avoiding any damage to the car.

" 'Dickie!' I screamed. He was down, not moving. I climbed out of the car and ran to him. 'Dickie!' I shouted as I reached him. There was blood on the street, and the back of his head appeared flat, crushed. His arms jerked as if he was attempting to get up, and then they were still.

" 'Get up.' Big Pat snarled and kicked him in the side. When Dickie didn't move, Big Pat began to realize what he had done.

" 'He's dead!' I shouted and grabbed Big Pat's arm. Big Pat responded by grabbing my right arm with his left, wrenching his right arm from my grasp, and grabbing my shirt. He picked me up and held my face close to his.

" 'You're part of this,' Big Pat said. 'I fall, you fall. You say anything, and I'll kill you dead, as dead as your brother.' I was sure he meant it; as sure, as I was that Dickie was dead. Big Pat let me go. He told me to open the trunk.

"Without thinking, I followed his directions and went to the car to get the keys from the ignition, and did as I was told. Big Pat picked up Dickie, limp and lifeless, blood dripping from his crushed skull. I turned away as Big Pat shut the trunk over Dickie's crumpled body. I got into the car. Big Pat soon followed.

" 'What are you going to do?' I asked. 'Should we take him to a hospital? Maybe they could do something for him.'

"Big Pat grabbed me again, pulling me closer.

" 'He's dead. So what do we tell them? I was fooling around, and we just sort of ran him over? No way. Got it?'

"Big Pat didn't say anything more to me as we drove off, and I didn't know what was going to happen next. Big Pat drove around for a time before he headed to his home. He backed the car into the garage. Big Pat had me get out of the car to help him hoist Dickie's body into the small loft at the back of the garage. That's when I realized ..." Steven paused.

"Realized what?" The officer said impatiently.

Steven had a distant look, a tear at the corner of his eye. He tried to talk but instead sobbed convulsively. His composure was gone, his eyes moist, his being racked by shame. Guilt overwhelmed him. He took a deep breath and held it, hoping to regain enough composure to be able to continue. The consequences no longer mattered. Fear of Big Pat no longer was a concern, as death seemed a welcome alternative to the loathsome contempt he already felt for himself. Death? You can't kill what is already dead. He took another deep breath and tried to continue.

"You see," Steven said between sobs, "you see, Dickie wasn't dead."

"What do you mean?" The officer interrupted.

"It took some doing to get Dickie into that loft. Big Pat had him draped over his shoulder as I steadied the ladder from below. We placed him on a narrow ledge that had a low rail that hid him from view. We placed him there, his arms folded at his sides, legs stretched out, wedged in tight in a space just big enough for his shoulders. As we turned to leave, we heard a long, low gurgling sound as Dickie gasped for breath. That horrible sound hit me in the pit of my stomach and flipped it. I thought I was going to puke. I can still hear that awful, awful sound, as I lie awake at night. It's there in my room. I hum to myself to drown it out, but it is still there, calling me for help. When we heard that sound that day, we stopped dead in our tracks. I turned and started back to the ladder. Big Pat stopped me.

" 'You hear anything. I didn't hear anything. Got it?' Big Pat said, with a cold, hard stare. Then that sound came again. Long, slow, and painful, like air running through thin reeds, a death rattle. 'You didn't hear anything,' Big Pat said again, holding my arm tightly.

" 'He's alive! Maybe we can help him,' I pleaded.

" 'Nobody can help him. You saw his head. You saw him hit the ground.'

"Big Pat dragged me from the garage, but that sound still was ringing in my ears. I sneaked back into the garage later. I had to. I brought a canteen with water in it. I didn't know, I thought we should have tried to save him. I poured water into his mouth, but he wouldn't, probably couldn't, drink. I held him, rocked him, and told him I was sorry. I had to be careful. Big Pat watched the garage from his room, and he watched me. I returned two more times during the next 24 hours. The last time, I was sure he was dead. He was cold and stiff." Steven paused, looked around the room slowly, but avoided eye contact with the officers.

"Big Pat came for me two days later. He told me I had to help him. Heat was working on the body. We had to get rid of it. After dark, he made me help him put Dickie's body back into the trunk of his car. He said he had a plan. We would bury Dickie by the creek near the old powder mill. Big Pat was going to quit school and join the army. He figured he'd be safe in the army; and, as long as I didn't say anything, I'd enjoy a long life."

Steven began to sob again. It was over. He had unburdened his soul and exposed his terrible guilt. The officers looked at him with puzzled unsympathetic expressions. How can a brother do this to a brother? How could Steven allow his brother to lie there dying without helping him? Perhaps Big Pat could shed some light on the facts.

Fort Benning, Georgia:

Big Pat reported to his sergeant as requested. He seemed composed to the police officers that greeted him in his sergeant's quarters. Big Pat knew that this would eventually occur, and he had practiced his reaction to the sudden appearance of the police in his head a thousand times, where he had written and rewritten his lines, scenario after scenario. Now, it was show time.

Big Pat never trusted Steven to keep his mouth shut, and he fully expected that Steven would impugn him in this crime. But he hadn't heard what Steven had said, and he didn't know what the police knew. He read the newspapers from home that he had his mother send him daily. He called his mother often to get what information he could.

"What a terrible thing that happened to poor Dickie Paponovitch. Poor boy. He was always so unhappy, may he rest in peace," Big Pat's mother would say. There was little more that Big Pat could learn.

Big Pat sat half-listening as he endured the officers explaining that Dickie Paponovitch's death was under investigation, and that he was a suspect. He could have an attorney present. They cautioned him regarding what he might say and explained his rights. He didn't care. He was going to sing, and sing loudly.

"I didn't kill Dickie. It wasn't my idea to kill him. It was Steven's idea. Oh, how Steven hated his brother. He'd planned it for weeks. He was tired of having his parents spoil little Dickie. He was tired of having Dickie get whatever he wanted. When Dickie threatened to tell his parents that Steven used drugs, Steven had had enough. I didn't take Steven seriously at first, but he was serious.

"I didn't realize Steven had gotten behind the wheel of my car when I left the car to reason with Dickie that day. We let Dickie hang with us. Of course, he had to give us something in return, things. As usual, sometimes even if he got his way, he'd take back or not come through with whatever it was we wanted from him. Steven had gotten really abusive with Dickie that day. He kept calling him a 'stinking little wimp' over and over. Dickie was tired of Steven's abuse. He had gotten out of the car and started to walk away. I got out and started to run after him. I was startled by the sudden whine of the car's engine, and then the squeal of the tires as they gripped the asphalt and the car lurched forward. I jumped out of the way as the car sped past me toward Dickie. Dickie turned, but Steven never slowed. The car struck Dickie. Dickie flew backward, banging his head on the street.

" 'What are you doing?' I screamed at Steven.

" 'What we planned to do,' Steven said coldly without the least bit of emotion.

" 'Not we, you, you!' I said.

" 'No, we're in this together,' Steven said as he wiped the steering wheel clean. 'Together, you and me. As far as I'm concerned, you drove the car. Not me. You did this. Not me.' he said.

"Steven instructed me to put Dickie's body in the trunk, and eventually into the loft in the back of my garage. I felt compelled to do as he said. The more I did, the more compelled I felt to follow, and the deeper I got into it.

"But, as horrible as all this sounds, the real horror came when we realized Dickie wasn't dead. He breathed, and kept breathing. Steven kept insisting on doing nothing. He wasn't going to let me interfere with a 'good thing,' as he put it. When Dickie finally died, three days later, and Steven got rid of the body, I couldn't wait to leave home and join the army. Once I heard the body was found, I knew it wouldn't be long before you would be knocking on my door. I know I'm in trouble, but I hope that psycho, Steven, gets what he deserves."

The officers looked at each other with confused but doubting circumspection. They had heard Steven's tale, now Big Pat's. Did each teller have something to hide? Which story was correct? Perhaps Steven did abuse, or had abused, drugs. Perhaps that was the reason for his social withdrawal and academic failure. Perhaps Big Pat had driven the car that day, and now he was just trying to throw the burden of guilt on to Steven.

They arrested no one pending further investigation. But there was little to investigate. No witnesses could be found that had seen the three that fateful day. The section of road where the crime was alleged to have occurred had been widened and re-paved early that following fall. Big Pat's car had been totaled in an unhappy encounter with a tree and was sold subsequently, for scrap. The garage behind Big Pat's house mysteriously burned down, a total loss. Examination of Dickie's remains, badly decomposed though they were, confirmed the occipital fracture and a cervical fracture but revealed little else.

The officers returned to talk to Steven. When asked to submit to drug testing, he refused. He excused himself to go to the bathroom. When he did not return after several minutes, the officers investigated and found him hanging by his belt from the skylight. He was nearly dead. Although they tried to resuscitate him, he suffered enough brain damage never to regain consciousness. Blood tests at the hospital confirmed alcohol, marihuana, and cocaine. Big Pat remained in the military, under surveillance, but apparently not watched closely enough. He was found behind one of the barracks, dead, his neck slit from ear to ear. The military police never discovered the motive for his death. The assailant(s) were never found.

And, that's all I know. I have never forgotten that look on Dickie's face the last time we played together, when George made him leave. Maybe it wasn't arrogance and defiance, but sadness at his inability to be a better friend. I can only wonder if he'd stuck with us, or we with him, perhaps all this could have been avoided.

Epilogue:

My death, premature as it was, remains a mystery to those interested. The importance of the correctness of the facts declines with each passing day, as it should. The principles are all gone: Steven, Big Pat, and, of course, me. For my parents, it was that feeling of failure, where did we go wrong sort of thing, and depression for the loss of, not just one, but two sons. The cops remained interested the longest, I guess, perhaps out of the desire to solve all crimes. Poor Joe, the affair so affected him, but few of the other kids on the block seemed to care.

I'm not sure there was a crime, at least of murder. There seems to be no question that some charge should've been levied; what charge and against whom was the problem. It really doesn't matter what I think. The cops thought I'd been murdered, and that's all that mattered to them. The way Steven and Big Pat had comported themselves with the police convinced the authorities something was rotten. I was the only thing rotten. Ten months in the ground beside Cobbs Creek, damp, infested with rats, and insects, I was rotten all right. Fortunately for me, now, my physical attributes are mundane, irrelevant.

In any event, I'd like a chance to explain myself, if not for me, at least for those who judge me. It's amazing how mature and insightful one becomes when allowed the luxury of eternal reflection.

I admit it. I was as I have been described. I didn't have friends, except for maybe Joe. I didn't much like myself, so why should others have liked me? I pushed people away. I learned to dislike my peers. They seemed happy, and they had no right to be, especially if I wasn't. They were beneath my family and me anyway. They were poor; we were rich. It was for me to decide where I played on the field, when I should bat; and if a play were close, whether I was out or not. What gave those low-rent peons the right to call me out? It didn't matter to me if the game ended when I left, as I marched away with the necessary equipment. They brought that on themselves; they had! But they never begged me to stay. They never reversed a call, and I never learned. Joe seemed to care for me. I'm amazed this all still haunts him. He tried, I wasn't receptive.

Big Pat, he was a piece of work. A tough arrogant bully best describes him. He had a car, '57 Chevy, rebuilt engine, a major attraction for me. I was too young to drive. I never questioned Big Pat's attraction to me. In retrospect, now, I see the attraction stemmed from his need to dominate everyone. Perhaps that's why he had no other friends but Steven and I. Big Pat was my idol. I saw no one tell him where to go or where not to go. People in a crowd moved apart as he walked through to avoid being pushed aside, because that's what he'd have done if they hadn't moved. I got to walk in his wake. His size made him impervious to challenges. Sure, there is always someone faster, bigger, tougher, better. It's just that Big Pat hadn't met that someone yet. He was mean and impulsive. Had there been a vote in the neighborhood, I'm sure he'd have been nominated most likely to live out his years in a cell, while wearing a tailor-made orange suit with numbers printed on front and back. I was attracted to his power, that sense of invincibility. True or not, I believed nobody liked me, it's no wonder he learned to dislike me as much as everyone else disliked me. I made myself an easy target for bullies and accepted their ill-will towards me as deserved. Does that make me a tragic figure?

Steven was Big Pat's only friend. That is, if you consider friendship a sort of business arrangement where Big Pat supplied Steven with drugs and alcohol, and Steven supplied Big Pat with me. Steven was just as arrogant and mean as Big Pat; they were quite a pair.

Steven rarely spoke to me, except to abuse me verbally and physically. I'm convinced now, that it was my existence that bothered him, perhaps nothing more. The fact that we breathed the same air was too much for him. No, it wasn't just the air we shared that bothered him, it was the fact that we shared the same parents, and it was ever clear who was their favorite. Steven never met our father's expectations, and our father's arrogance and stubbornness were equal to his. They could not communicate except to be angry at each other. Mother's relationship with him was no better. So, for me, at his expense, as I believe he perceived it, all their love translated to whatever I wanted, I got. The only thing I didn't get was my brother's love. When I turned thirteen, lonely, with no friends, and was given the opportunity to travel with Big Pat and Steven, I was willing to do anything. I would suffer their jokes and sadistic whims. They'd let me tag along with them, if I kept my mouth shut and did what they asked, run errands, buy them food, steal, purchase drugs on the street, whatever.

Now, lets get to that fateful day, the day of my death. It really wasn't their fault. They were irresponsible, but then, aren't all teenagers? They were governed by impulse, not instinct, for they had none. Who am I to talk? I lived by my emotions, not my conscience.

I was in the back seat. Big Pat and Steven were planning to go to the seashore that evening. The seashore was less than two hours away. They could sneak down and get back without our parents knowing. When asked if I could go with them, they laughed and said the question did not dignify an answer. I threatened to tell our parents if they didn't take me. They threatened to tie me to a tree, strip me, piss on me, and leave me there. Steven really got off on that idea. I thoroughly believed they would do it. We were traveling down Karacong Drive, when I rolled down my window and threatened to jump out if they didn't stop teasing me.

"Maybe you should jump," Steven said meanly. "Pat, go faster. If he doesn't jump, there's a place up ahead close to the skating pond where we can tie him to a tree."

I was in a panic. Not willing to jump, I waited until Big Pat stopped the car before I tried to escape. Before I could get out, Steven and Big Pat reached back and got a hold of my legs. I was half out of the car, thrashing and twisting. I grabbed the ground for whatever I could get my hands on. I connected with a half-rotted stick and swung it at the two of them. The stick fell apart as it hit them but did no harm. Fortunately for me, they instinctively covered their faces and let go of my legs as pieces of the stick flew past them. Off I went. I heard Steven say something to the effect that the little bastard is dead now. I didn't realize how true that was to become.

They got back in the car and drove north. I hid in a bush by the road for a while before coming out. I started to walk south on Karacong drive when I heard the unmistakable sound of the glass packs on the mufflers of Big Pat's car. I knew they'd be coming past looking for me, so I dove into the brush by the roadside, and waited for them to come around the curve. Just as they came around the curve, I jumped in front of them. My intent wasn't to die. I just wanted to scare them. Big Pat hit the brake; the car hit me.

I didn't die immediately. It was pretty much the way they told it from that point, although their participation was mutual. I would've liked Steven to try to come for me as I lay dying like he described it, but he didn't. I knew Steven used drugs, but I wasn't aware of the extent of Steven's drug abuse at the time. I'm not surprised that Big Pat died the way he did. It was his destiny.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.