Valery plays the role that Ivan Karamazov, had he lived, would have played in seeing Christina through the birth of their child, Deborah.

Part II (continued)

The first contractions came on suddenly and fiercely and Tina was in the bathtub. The midwife, Miss Gelb, told Mrs. Morgan they might as well leave her there if she couldn't get out because of the pain. Valery arrived and rapped on the bathroom door, afraid the child might drown when it came out. Mrs. Morgan opened the door a crack.

"Drown! Is it drowning now in the sea of Tina's guts? Don't you know anything about childbirth?"

He was two when his mother died in childbirth. He had never approached one since. "Nothing at all."

"Well, Miss Gelb and I do."

"But in the bathtub?" Valery pressed.

Mrs. Morgan came out and grabbed Valery's head and pressed it down into her immense bosom, rubbing his scalp briskly with her knuckles. "Go buy yourself some whisky and settle out in the parlor. This will take time. It's her first and she has hips as narrow as a drainpipe."

A doctor came, Dr. Applebee. He had no coat, no tie, just a dingy shirt open at the collar and a vest. Seeing Valery's bottle on the table in the parlor, he invited himself to have a nip before he looked in on the "expecting one."

Tina cried out, as she had been doing periodically. Applebee told Valery, "That's half what you'll hear when it's time."

Valery said, "It would be easier if I could see her. Just listening is driving me mad."

"You haven't seen her? Come on, man, no harm in that. Drink up. We'll have a look."

Dr. Applebee rapped on the bathroom door. Mrs. Morgan and Ms. Gelb made way.

"For him, too," Dr. Applebee said, referring to Valery behind him.

"Him? It would be indecent!" Mrs. Morgan said.

"He's the father, for God's sake."

"No, he isn't."

Valery stood behind Dr. Applebee in the little hallway. "I'll go back to the parlor."

"No, let him come in," Tina said.

"It isn't proper," Mrs. Morgan objected.

"Please. It's all right. You leave, all of you. I want to talk to him alone."

"I'll cover you with a towel."

"Don't cover me with a towel!"

Valery stepped into the bathroom and looked down at her, drenched in perspiration and bathwater. Her face was florid and puffy. A blood vessel had burst in her left eye. Her breasts and belly were immense. She had her legs crooked over the rim of the tub at the knees, her feet hanging down in the air.

"I had no idea there were things inside me that could hurt this much," she told him. She was panting but frank, trying to speak normally despite the circumstances.

"I'm so sorry."

"Don't be sorry. It's good."

"Of course."

"Look at me, Valery, I want to say something to you."

He forced himself to stare into her blue eyes. And then she spoke with the kind of abrupt frankness he could only imagine she had first directed at Ivan.

"Now I have to take care of this baby and you said you would take care of it, too, so you have to take care of me, and I have to take care of you."

He was elated. These were the most thrilling words he'd ever heard. "I can't let you worry about me. Worry about the child."

"You can't stop it. I need you. You have to be all right, and now that it's here, I admit it. If it's a boy, we call it Valery with a 'y.' If it's a girl, Valerie with 'ie.' Ivan would want that."

He could not help smiling -- the first time he had smiled at the mention of Ivan's name since he had been killed.

She stopped looking at him and began panting more quickly. He called the others and now was permitted to stand behind them and peer through the open door at Mrs. Morgan toweling Tina's head and Miss Gelb massaging her legs and Dr. Applebee obscurely bent over her middle, prying between her thighs.

"Get me a baking pan or something," Dr. Applebee said.

Valery went into the kitchen and found one. He slid it on the floor to Dr. Applebee who was down on his knees now.

"Drain the water," Dr. Applebee said.

Mrs. Morgan slid her arm behind Tina's back and pulled the plug which sucked and croaked with relief as the water began gurgling out.

"Kick me my bag there, Valentine," Dr. Applebee told Valery.

Valery nudged Applebee's large black leather bag to him with his foot. Applebee pulled out a spoon-like device hinged at the middle of its handles.

"It's coming. Here she comes! Get ready, nurse midwife! Get the towels!"

Miss Gelb already had the towels. Christina let out a growling groan. Valery heard the clatter of the forceps on the tub bottom and then saw Applebee pull a scalpel out of his bag with which he cut the umbilical cord that was attached to a miniature being Miss Gelb was catching and wiping and thumping on the back with two fingers to get it to howl like its mother, which it did, squalling and squealing, whereupon Miss Gelb pushed past Valery to the kitchen table where she laid the child out like a pot roast, ready to be seasoned.

Tina's face somehow had grown glowing and beatific. Her head was turned so she could follow the disappearance of the child. Dr. Applebee continued handling her pudenda, extracting a formless mass of afterbirth and dropping it in the baking pan. Still on his knees, he poked at it with the scalpel he'd used to cut the umbilical cord.

"Anything wrong?" Valery asked.

"No, all's fine."

"What is it?" Tina asked.

"Girl," Mrs. Morgan said.

"I wish you would let us call her Christina," Valery said.

"I don't want her to have my name."

"Then what shall we call her?"

"Deborah."

He said all right.

It took three of them, Dr. Applebee, Mrs. Morgan, and Valery, to get her out of the tub.

#

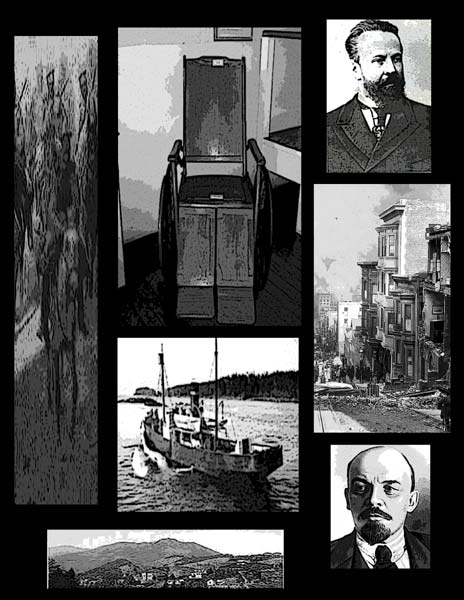

They continued to live as they lived but without Valery ever missing supper and sometimes, if he could manage, visiting the house in the daytime. And of course on Saturdays and Sundays Valery, Tina, the baby, and Mrs. Morgan acting as nanny took walks and had meals in restaurants where children were welcomed. Valery grew less attached to his own fine apartment on Nob Hill with its balcony overlooking the bay and large closets hung with armies of clothes in perfect parade formation ready to attack, and more at ease in the weathered gray frame house clinging to a steep hillside that felt more like a nursery than a home, with Tina not always dressed, the scent of talcum powder and sweet baby poop everywhere, and Mrs. Morgan watchful as a crow, sensitive to the inchoate bond forming between the mother and the man who wasn't the father but somehow played that role. He didn't spend the night. Sometimes he sat up telling Tina about Russia and they discussed the Karamazovs, but when Mrs. Morgan arose at five (she now slept in the middle bedroom, happily enough) the consul (as she affectionately called him) was gone, and Tina was in bed with the baby nestled under her arm.

One day Valery received a query from Ambassador Count Cassini in Washington wanting to know about John Patmos. Was he really gone, no longer publishing his anti-Czarist invective in the San Francisco press? Valery wrote that Patmos did appear to be gone, but San Francisco was still buzzing with talk about northeast Asia, where Japan and Russia were jostling over Manchuria and Korea and who had rights to what. This exchange with Ambassador Count Cassini prompted Valery to realize that while he could not perpetuate John Patmos's apocalyptic forecasts publicly, he could do something privately that might be of use. He wrote out in hand his assessment of what he was hearing about the burgeoning crisis across the Pacific, and sent it to the address in London where Ivan always had sent Patmos's clippings. He gave the note no heading and didn't sign it, but he ended with a prediction of war. A week or ten days later, he added a few details, noting that the Japanese foreign minister had been educated at Harvard, and that the Japanese emperor was said to have great confidence in him because of this link to America, which augured ill for Russia. Valery knew Lenin, if he received what he wrote, would want to know this. Lenin wanted to know everything, so Valery kept writing these notes. The Japanese emperor, he wrote, was a curious phenomenon. Whereas the Czar was Czar of many places, the emperor wasn't. The Japanese sense of empire seemed to be more linked to the emperor's status as a demigod, not to political affairs. But on the other hand, Valery was told that as of 1893 the emperor became both head of state and leader of the Japanese imperial headquarters. So things were changing in Japan, and they might take flight, uninhibited by territorial limitations and abetted by industrialization. Many Americans complained to him that the British seemed to have all the luck helping the Japanese build up its navy. "We'd like to build a few of those warships for them ourselves. What would it hurt?"

Little findings. Things he heard. The odd bit of news that Ivan would turn into a more fulsome prophecy, or tale, or a pointed joke. There was a bet-maker's shop in Chinatown in San Francisco, and the odds were that Japan would invade and take over Korea in two years and China in three.

"Did you hear that, my friend?" a San Francisco lawyer asked him over lunch once.

"I had no idea such things were the subject of gambling," Valery said.

"The Chinese will bet on anything, even the date of their own demise."

"What about the Koreans?"

"Oh, the Koreans think they're already dead. Always have."

Valery wrote this exactly as he heard it and slipped it into an envelope for London. He wondered if he'd ever be able to pass along news from Mitya and Aaron; it seemed to him possible they might bring exceptional news, but again, he had a strange confidence that what mattered to Lenin, wherever he was, was everything, not anything in particular.

One afternoon Ambassador Count Cassini called Valery on the telephone. His voice boomed across the continent with megaphonic force. He said the Japanese had attacked and damaged the Russian fleet in Port Arthur, but the telegraph line from Port Arthur to Vladivostok had been cut, so he lacked details. Did Valery know anything?

"Sir, that's thousands of kilometers from where I sit."

"There's no talk?"

"None. When did this happen?"

"I'm told in the middle of the night two nights ago."

"How could it have happened?"

"The little yellow monkeys snuck up on us. We'll crush them."

Valery said, "Of course, we will."

Ambassador Count Cassini said he'd like to know what Valery would think about sailing out there and having a look. "I want someone advising me who knows what he's talking about."

"But, sir, we're accredited to the Americans."

"Exactly why I want to know what to tell them!"

It was a quiet enough afternoon in San Francisco until that moment. Valery held the telephone receiver away from his head and rather hated it. "The telegraph line will be back up again soon, won't it?"

Cassini asked what difference that made. He didn't need a telegram to give him his script. "I'll tell the Americans to not meddle. "

"And to condemn Japan?" Valery suggested.

"Yes, yes, of course. Who do they think they are? Asia is mine -- no one knows it better -- and I shouldn't be here. I should be there defending what I have done. My Manchurian convention would have held things in place, and I don't want you to think going out there is a subject I won't touch on again. Find things out! Tell me what you hear!"

Valery wrote to the address in London: The Russian ambassador to America was caught by surprise, just like the Russian fleet at Port Arthur on the Liaodong Peninsula. He worries America will meddle, or not support Russia. He believes the Russian government does not understand Asia and has overreached itself. Then he dated it -- February 9, 1904. He did this sort of thing regularly for years with one variation -- he received an empty envelope one day with a return address in Zurich. Thereafter, that's where he sent his news of the world.

"The Russian ambassador to America was caught by surprise, just like the Russian fleet at Port Arthur..."

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.