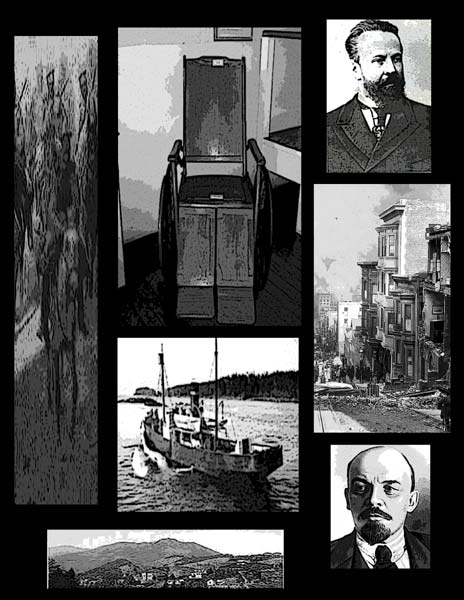

Conclusion: Valery has obtained what passes for Lenin's writ, but it's not worth much in Russia, 1918; more powerful are the Chekist agents Dzerzhinsky sends to Skotoprigonyevsk, although they only deepen the chaos. Lisa Khokhlakov and Katerina Ivanovna Verkhovtsev must decide whether to let Valery try to spirit them away to America ... or continue to insist on their rights and justice in Skotoprigonyevsk.

Part V

When Valery arrived at the inn, he found Katerina Ivanovna seated at the table by the window with two men at her side, detaining her there. One was bald with the face of a battered anvil. The other was a pockmarked red-bearded weasel. The rest of the room was filling with the members of the soviet of Skotoprigonyevsk, motley and disorderly. Now there were six Cheka men along the bar, behind which stood the innkeeper, who gave Valery a sympathetic smile when he saw him enter the tavern room.

Valery made his way to Katerina Ivanovna.

The anvil told him, "You are not permitted to address the accused."

Valery ignored him. He asked Katerina Ivanovna, "Are you all right?"

She nodded. "But go away now," she said, worried about the anvil who was rising from his chair as if preparing to do something.

"I saw him," Valery said to her.

"Who did you see?" the pockmarked red bearded weasel asked.

"Lenin. And Trotsky. And Dzerzhinsky." He didn't mention Chicherin because a foreign minister meant so little at home.

The anvil said, "What about God? Wasn't he there?" He pushed Valery away, knocking him back two or three steps. "She's accused and doesn't answer to them or you. She answers to this soviet. It's how things are."

A small disruption, the size of a moth hole in a blanket, disturbed the impatient chatter in the room. The visitor had been pushed. So noted. The monks were back, hoping to replead their case. A man walked around saying he had recruited six men to go battle the Whites but needed twelve.

"That will make me a captain, and as a captain, I will be able to look after our boys better." He wanted another man's three sons.

"I need those boys," the man said.

"All three?" the recruiter asked, feigning surprise.

"Vasily Vasilievich, what do you know about being a captain?" a woman, the three boys' mother, protested.

Vasily Vasilievich lifted the fold of his belly overhanging his belt to reveal a revolver. "I know how to use this."

"Where did you get it?" the lady asked.

"Don't matter where," the father said. "Give it back, Vasily, or you'll get hurt." He nodded his head in the direction of the six Cheka men arrayed along the bar.

The room kept filling up in twos and threes. Valery had sat in the train, cramped between a soldier who was drunk and an old woman who smelled of death or rotten eggs, trying to prepare some kind of speech in Katerina Ivanovna's defense that could not be mere rhetoric or recitation of past sacrifices. He had foreseen the sour, surly mood of the Skotoprigonyevsk Soviet that now surrounded him because he'd been staring at it since the day he returned to Russia. No one was happy. Everyone had sacrificed. No one had hope. On the train he and the drunk soldier and smelly woman had faced a fat, miserable woman with two children in her lap, another crone crumpled up against the car wall like a piece of rotted meat, and a malnourished peasant who somehow had squeezed into what was supposed to be first class but of course could not be first class anymore, far from it, a great disappointment to the peasant whose assertiveness had gained him nothing. The window was stuck open, so the compartment was frigid, and the passageway outside was so packed that you couldn't get through to the lavatory. Men and women urinated where they stood, though one after the other Valery held the fat woman's two little boys up to the window so they could squirt astonishing arcs of urine outside. The blunt force of the way people had spoken to one another shocked him. "Get out of my way!" "Keep your gas to yourself!" "Dribble on your own feet, not mine!" "Keep your filthy hands to yourself!"

Two men squared off against the recruiter and said, "No more war, got it? We're at peace! There aren't any 'Whites.' That's all made up!"

The recruiter in his oatmeal-colored cap, tattered black tunic, gray pants and high boots had had enough. "We're not at peace! The whole world is against us now, don't you see? Germany our friend? It isn't that way. We need our Red Guard to protect us. That's all I'm saying. Long live the red!"

He was shouted down and then punched several times. Anvil went over to help do this. Valery seized the chance to sit beside Katerina Ivanovna.

"Did you really see him?" she asked

"Yes."

"And he remembered me?"

"Of course!"

"Even though I have not been able to send him anything for so long?"

Valery realized how important it was to her to hear that she had standing with Lenin. "He emphasized that almost no one believed in his project and supported it for so long," which, of course, even if Lenin had not said it, was true.

She registered this with satisfaction. "What else? Did he send them here?" She was referring to the extra four Cheka men at the bar.

"Through Dzerzhinsky."

"You met him, too?"

Again it was a kind of lie. Da, da, was all Dzerzhinsky had said, like some kind of hideous infant. "Yes, in the Kremlin."

The word Kremlin seemed to affect her even more than the famous names. "What do we do? What are their instructions?"

He was almost convinced that if he told her something and said it was what Lenin wanted, she would do it -- anything -- but was impeded from testing this conviction by the arrival of Lisa Khokhlakov in her wheelchair.

As always she was hoisted up on the little platform and turned herself around and began getting her writing materials in order as if she were a secretary alone in her office going through her morning procedures, unobserved by a soul. As she did this, putting her writing board in place and setting her ink pot and notebook upon it, the crowd returned to its murmuring and rumbling and Anvil came back and retook his seat from Valery, who stared at Lisa Khokhlakov until, as this always happens, she felt his stare and her eyes flickered upward and toward him.

"Well, what do you have to tell us?" she asked. "Have you been to Moscow? Do you bring us news from your friend Lenin, Madam Verkhovtsev's protector?"

Valery said, "Yes, of course." He felt he must as terse and stiff with Lisa Khokhlakov as she was, through him, with Katerina Ivanovna. Whom she hated. This was quite clear. The woman who had had more of Ivan's love, and even of perverse Dmitri's, than Lisa had ever had of Alexei's. "She is needed to further our efforts overseas. I am to take her with me, so you will have to release her."

Katerina Ivanovna gasped, "No!"

"Where overseas?" Lisa Khokhlakov demanded. "Do you take her to Spain?"

"New York," Valery said, deciding this matter on the spot.

"What about her property?"

"She surrenders it until her return."

He couldn't look at Katerina Ivanovna as he said things because he wouldn't be able to say them if he did and because if he didn't say them directly to Lisa Khokhlakov, she would not believe him.

"When will that be?"

"That's not known."

Katerina Ivanovna could bear it no longer. "But I won't go! I won't give up my house! Tell them what I've done! Tell them what Lenin said about me!"

Suddenly the innkeeper yelled, "Lenin and all his cronies are pieces of shit!" and a Cheka man on the other side of the bar turned and in one sweeping motion pulled out his pistol and shot the innkeeper in the chest. The innkeeper was thrown back against the shelving and then disappeared behind the bar.

Two other Cheka men pulled out their weapons and held them high in the air.

"What are you doing?" Lisa Khokhlakov screamed. "Do you mean to kill us all?"

The forty people crammed into the room huddled against one another like the people in the miserable train in which Valery had spent the night. The fairest of the new Chekists now spoke. He was trim, calm, thin-lipped, self-possessed.

"This soviet is dissolved. Go home. When it is reconstituted, we will let you know where and when it will meet."

The little girl behind the bar began screaming. No one could see her, but they all knew it was her.

People began rushing for the door, but now the recruiter unwisely drew his revolver, perhaps in intended alliance with the Chekists, though for his trouble he was shot in the face with a great boom and flipped backward as people pulled away from his splattering head. This intensified the rush through the door, punctuated by cries and moans and shrieks of grief and terror. The Chekists shot again and again for the violent sport of it. The little girl came out from behind the bar, her face, blouse and hands covered in blood.

"My papa! My papa!"

A woman grabbed her to protect her. She fought to return to her father. A man clutched her by the hair and helped the woman get her under control.

The gunshots had sounded like cannons to Valery, nothing like the snap-snap of the discharges that he had heard years ago in California, the first killing Ivan, the second killing Smedlov, but he could not escape the sensation of being propelled back to that day, for surely this finally was the end.

Anvil and Weasel spoke to him. He hardly heard them, just captured their sense: Take her with you then, meaning Katerina Ivanovna. Then, they, too, were gone.

For reasons attached to the unreason of the moment, two of the Chekists dragged the recruiter's body and three other bodies behind the bar. These bodies served as virtual paintbrushes, describing sweeping red curves of blood on the floor, one, two, three, four.

Now it was Katerina Ivanovna seated at the table by the window along the street, Valery standing alone in the middle of the tavern, Lisa Khokhlakov still on her platform, and the Chekists, two of whom went to guard the inn's front door and two the back.

The women were stunned.

"Is this how it is? Is this what we planned?" Katerina Ivanovna asked.

"Go with him. Do as he says," a Chekist told her.

"I won't! I will stay! This is my home!" Katerina Ivanovna yelled at him. "I gave Lenin all my money -- all of it! And now I will lead the new soviet. We will do this together."

The Chekist shook his head, unaffected by her extreme emotion and determination. "No, you're a class enemy, and none of you can stay."

"None of us?" Lisa Khokhlakov asked.

"You either. You above all," the Chekist said. He and the other Chekist walked across the room and lifted Lisa Khokhlakov down to the floor.

"How can I go anywhere? Look at me! Look at me!" Lisa Khokhlakov demanded, holding up her almost skeletal hands and arms. "I can't go to America! How can I? Leave me alone. Let me go, I say."

She tried to wheel herself away, but the Chekists held her chair in place.

Valery kneeled in front of her. "I will take you to New York. Alexei's son Aaron lives there, and you'll meet him. Then we can go to California, and you can see Alexei himself, whom I know you love so much. Russia is no place for you anymore, Lisa. Come with me now."

Lisa Khokhlakov bared her teeth as if she would bite Valery. "Alexei, who abandoned me? What are you saying, you fool? Don't you understand I hate him, I've always hated him?"

Katerina Ivanovna tugged at Valery's shoulder to get him to stand up. "Give her to me. I will take care of her. You go. We'll stay. We're not leaving. Listen to us, Valery. We're not leaving!"

Lisa Khokhlakov emitted something like a laugh at Valery's astonishment and quandary. What could he do with such women? He could do nothing. They were both against him.

"You won't survive," he said to them. "Don't you understand?"

"Nor anywhere, then," Lisa Khokhlakov said. She glared at the Chekist holding back her wheelchair by its handles. "Let me go!"

The Chekist let go. Katerina Ivanovna stepped behind the wheelchair and took the handles.

Valery knew there was no time left to persuade or debate. Time was over. This was the end. He pulled out the piece of paper Lenin had signed and put it in Lisa Khokhlakov's lap.

"Take this."

"What is it?"

Katerina Ivanovna stared over Lisa Khokhlakov's shoulder and saw it for what it was. "Lenin's autograph."

"Pah!" Lisa Khokhlakov spat, brushing the paper off her lap onto the bloody floor. "We don't need it. We'll sign our death warrants ourselves."

Valery stepped aside and watched Katerina Ivanovna push Lisa Khokhlakov out of the tavern, through the inn's entryway, and onto the street.

One of the Chekists said, "You'd better get going and take this with you." He bent down and retrieved Lenin's autograph, which he placed in Valery's hand.

Valery went upstairs to find that his things were still in his room. He packed them with his usual care, thinking that if he could make it to New York, that's exactly where he'd go, but whether he could actually get there, and what he'd do after that, who knew? He might not make it at all.

"Is this how it is? Is this what we planned?"

.

11/11/2012

05:42:23 AM