Part III

Having just lost his wife, Robert could barely drive, but there was no other option for getting to the hotel and in a crazy way, he was desperate to do it, leaving Sarah behind to tend to the body. All the way into the city, Suzanne stared out the windows, telling herself, I can't believe I'm here; I can't believe I'm here.

The first thing Kerry did when they checked in (Kerry and Suzanne were sharing one room and Emmy and Michelle were sharing another) was call the International Clinical Field Care (ICFC) office, only to learn that ICFC was having problems with the Ministry of Health. Their "location" -- where they'd work and live -- wasn't set. So hold on. Relax at the hotel. When Kerry told Emmy and Michelle, Emmy was blasé about it. "Okay, we hit the pool," she said. "After what just happened, I could use a break." But Michelle, now constipated, was pissed. She asked whether Kerry hadn't reconfirmed all the arrangements before they left. Kerry looked as if she were about to cry. Suzanne defended her.

"Of course, she did. She always double checks everything."

"Then what happened? Is this typical in Zimbabwe?" Michelle sniped, aiming at Suzanne.

Suzanne said too sharply (she knew it when she said it) "It's typical all over the world."

An odd moment of three against one ensued. None of them, Kerry included, wanted to hear this or be lectured by an older woman, especially one who had almost lost the backpack in which it turned out Emmy had her birth control pills. They had laughed about how much sex Emmy planned on having in Zimbabwe when this came out, but they weren't laughing now. They looked at Suzanne as if she were responsible for global incompetence. Well, at least I've pulled them together against me, Suzanne thought, and didn't say anything more.

The hotel had every feature you'd find in Dallas or Frankfurt. There was a pool and a workout room and a newsstand at one end of the lobby, which soared up into a cathedral-style ceiling. Across the wide avenue, there was a large, handsome park surrounded by dozens of contemporary office buildings. None of it looked like Salisbury, circa 1957, except the park. Suzanne thought she remembered the park -- the band playing and the cotton candy and ... "Look," her mother said, "now she's got it in her hair." She pulled Suzanne into a ladies room where she cupped tap water with her bare hands and poured it on her head, sopping her. Suzanne remembered how humiliating it felt to be stared at by the attendant selling toilet paper. She didn't have to be corrected so roughly. She'd just been excited by the music and begun swirling around without minding the puff of cotton candy in her hand.

But that experience was no worse than sitting by the huge swimming pool the next day -- at least she was dressed in shorts and a blouse -- when poor Robert and his neighbor Sarah, the gaunt woman with the ravaged eyes, appeared.

"May we speak with you, madam?" Robert asked her.

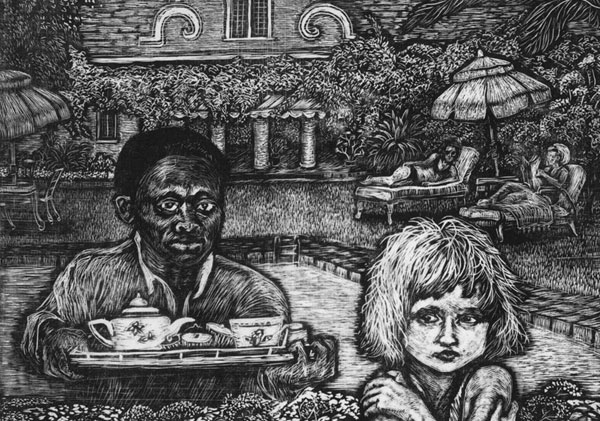

Suzanne called to Kerry, who was lying on her tummy out in the sun, flanked by Michelle and Emmy. None of them had their bikini straps fastened. There was a stirring and grabbing and covering up with towels that eventually led to everyone joining Suzanne at her table, where Sarah and Robert declined an offer of ice tea and Sarah, rigid with discomfort, explained why they had come.

When the shantytowns were demolished during Operation Murambatsvina, she said, some people were able to take refuge with relatives in the townships, but not everyone had that option. Thousands of families became homeless and took shelter wherever they could, such as the encampment where she and Robert now lived. These places were much worse than the demolished shantytowns. Sewage flowed everywhere and contaminated the groundwater. When the cholera broke out, the government established a clinic in a tent outside the barbed wire, but then it decided that there was no more cholera in Zimbabwe and the clinic was removed. This led to the death of her son, and Robert's daughter, and now Robert's wife, whom they had buried just before coming to the hotel.

"Government offers us free graves now, not free health care," Sarah said. "It is not just cholera. It is malaria, it is bilharzia, it is all the human afflictions. We beg you to come back and treat our sick. We have no nurses or doctors. We have no medicine. What can we do?"

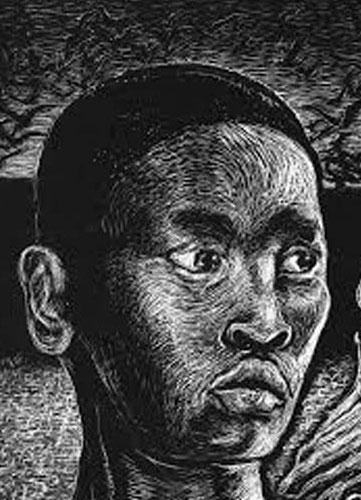

Sarah pressed her lips together expectantly, betraying more hope than anyone in her situation ought to possess. Robert, a stick of a man with a belt buckle fastened at the very last hole, tilted his head back, as if pulling away, anticipating rejection.

Emmy, Michelle and Suzanne looked at Kerry, whose face was drawn with jetlag and frustration. Throughout the morning, she had been on the phone with ICFC, reminding them of what the group had been promised in order to carry out its project. She kept pointing out to ICFC that they had funders expecting ICFC to be a good field partner.

Now Kerry restated for Robert and Sarah what she'd said repeatedly to the people at ICFC (who didn't even want to meet the group face-to-face yet; they were overwhelmed by the cholera epidemic showing up elsewhere in their program). She explained they had research plans in addition to providing general primary care, and these plans required them being located in the countryside, not in or around Harare. Emmy's public health focus would be on rural medical geography, Michelle's would be on gender-based disease vulnerabilities in a rural population, and Kerry would research complicating illnesses in a rural HIV positive population.

"But where are you going to do this if the ministry won't tell you?" Sarah asked.

"Sarah, we're going to be told," Kerry answered gently.

"Until then what will you do?" Robert asked, looking around at the pool, the beverage cabana beyond the diving board, and the waterslide on which a large white woman and a large white man were hooting.

Kerry reminded them that they had only arrived the day before, and it was a long journey from Connecticut to Zimbabwe.

"But we are dying, madam," Sarah said. "You have seen this with your own eyes."

Suzanne again was afraid that Kerry would begin crying; she might be too young for the kind of challenge she had set herself. All of the nurses looked young to Suzanne, just girls, so defenseless-looking wrapped up in their hotel towels. This request was impossible. She couldn't help envisioning the squalid encampment, wondering where it began and where it ended and how many people were confined there, and whether the government's intention was to let them die.

Emmy couldn't stand it. She had to say something. "Kerry, do you think we could talk to ICFC about maybe temporarily helping them somehow?"

Kerry grimaced. "Emmy, it's going to be hard enough, isn't it? We have a plan, we have commitments."

The night before, as they were struggling to fall asleep, Suzanne had listened to Kerry castigate herself. She felt she should have told Robert no when he asked them to help his wife. Why? Suzanne asked. Because, Kerry said, as a result of her bad decision, the first thing that happened was that the group had failed; it had failed because it gotten off plan; and it had gotten off plan because Kerry didn't have the self-discipline to see that this was not the way to invest their resources, meaning their skills and morale and sense of purpose. Now she reminded Emmy that they only had six months. They had to make one move to one clinic -- in the countryside -- and refine one set of treatment and research protocols. That was the plan. ICFC was still committed to it; this delay was not unusual; this delay was typical: you rode these things out.

Emmy said, "Okay, but I can't justify sitting around here in the face of ..."

She meant in the face of Sarah's indignation and Robert's disappointment. They were such powerful people sitting there -- Robert in his soiled gray trousers and yellow shirt, Sarah in her brown polyester dress, unconcerned with time or reason or plausibility, not caring that they were out of place, beyond being out of place. Robert said that he would make his house available as a clinic.

"I could sleep in my car. You could use my house to treat people!"

His house? His house was not a house, not a shed, not even a garage. It was a cinderblock box with a plywood floor and a plastic tarp for a roof. But it was probably the finest dwelling place in the whole morass.

Kerry said they couldn't possibly set up a temporary clinic in his house. They didn't have the supplies; it couldn't be made sanitary; there was no air. Suzanne remained silent, but it was difficult. She didn't know the right answer, only that this wasn't it. It was so urgent that they find some solution, some way to help. Wasn't that why they were there? How could they send these people away and go back to the pool?

"Why couldn't we talk to ICFC about giving us some supplies and maybe a tent? Who could object?" Michelle asked.

"The Ministry of Health could object. They just closed the clinic there."

"But these people still need help!" Emmy said.

Kerry stared at Michelle and Emmy to let them know they were compromising her leadership. But she said she would go back upstairs and try to talk to ICFC, if she could get anyone on the phone.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.