Part V

Because their rural assignment was going nowhere, Kerry received a conditional okay from ICFC to establish a temporary nursing clinic in Robert and Sarah's encampment. The one sensitive condition with the ministry was that they must refer cholera cases to one of the remaining emergency stations elsewhere in Harare.

"What about a doctor we could call in?" Michelle asked.

"There wouldn't be a doctor, just us," Kerry said. "This is general primary care. If we can do something, we do it. If we can't, we can't."

"Because these are nonexistent Zimbabweans like Suzanne?" Emmy asked.

"Let's stay out of the politics," Kerry said.

"Good luck at that," Michelle said.

But Suzanne watched Kerry push the others toward agreement, reminding them that responding to Robert and Sarah's plea was their idea, not hers. Kerry had her footing again, and her strength, comparable in its way to Emmy the rock climber's strength, rippled through her. She obviously was proud of her ability to get ICFC to agree. For her the choice was now black and white -- go along with this scheme for a week or stay at the hotel and do nothing. "We didn't come here to do nothing, did we?"

Suzanne was fine with the decision to give the temporary clinic a try. After finding her childhood home, anything that happened in Zimbabwe would be all right with her. Amadika and her children and grandchildren hovered in her mind like butterflies, innocent, incapable of harm or being harmed, and beautiful. She couldn't even recall all the grandchildren's names or their mysterious faces -- that was how overwhelmed she'd been, but she would always remember her first impression of Suzanne Vuamba's head, broad at the crown, narrow at the chin, and the way meeting Suzanne made her tremble. She wasn't a nonexistent Zimbabwean after all. Whatever connection she had established with this land and people when she was a little girl remained in force.

The first day was devoted to preparing the ground next to Robert's house for a two-room tent. On the second day the tent and an "instant clinic" pallet arrived on a flatbed truck from the ICFC warehouse. Robert and the truck driver set up the tent; Sarah headed off into the encampment to explain what was happening. Meanwhile the nurses and Suzanne broke down and assessed the instant clinic. There were two folding examining tables, a small field desk and flimsy stool, a footlocker filled with medications to treat basic ailments, a cabinet with bandages, splints, and implements, and, inadvertently or not, twelve gallons of oral rehydration solution (ORS, the nurses called it).

The four of them contemplated the ORS. Kerry said what everyone was thinking: if any cholera cases did show up, they couldn't risk sending them away -- they have to treat them as long as the ORS lasted. They simply wouldn't diagnosis cholera as cholera. They'd call it dehydration, and to prepare for these dehydration cases, they arranged pallets on the floor of the tent's second room. Michelle said she wished they could set up some IV lines. Emmy said they should be happy with what they had. Kerry seemed pleased that they were beginning to learn that evasion and adaptation were kissing cousins in the Third World. This would be a lesson to include in the training program they'd develop when they returned to the States.

A Ministry of Health representative, Mrs. Kahiya, visited them on the afternoon of the second day to give them forms to fill out for each patient they saw. She behaved in a way that Suzanne thought was routine, given the impersonal formality of officials everywhere, but annoyed Emmy, who did not like the way Mrs. Kahiya looked around the encampment in apparent disgust, or Mrs. Kahiya's jewelry and golden hair.

"Why don't you send someone over from the ministry to fill out these forms?" she asked. "We have our own records to keep."

"Your records have no validity in Zimbabwe, madam," Mrs. Kahiya responded.

"We're talking about people, not paper," Emmy said.

Indeed, people -- many people, stirred up by Sarah -- already were milling outside the tent clinic. Suzanne gave Kerry a look, urging her to intercede, which she did.

"Of course, we will do what you ask."

But she was too late to head off Mrs. Kahiya's displeasure. "I wish to remind you that your presence here is irregular and temporary. This settlement is not authorized and will be removed. And you are not here as a cholera clinic. You must send any suspected cases to --" She gave them an address Robert later told them was eight miles away.

People began coming to see them on the third day. They had bilharzia and malaria and ulcerated wounds and intestinal parasites and goiters and eczema and fungal infections of the feet, genitals, hands and ears.

The protocol was that the nurses would interview each patient quickly and then dictate the key points to Suzanne before proceeding with treatment. (This was to be one of Suzanne's functions: helping the nurses spend more time with patients, less time managing paperwork.) Michelle was good at this; Emmy less so, and Kerry was terrible. She had a hard time understanding Zimbabwean English and often asked Suzanne to interpret, which Suzanne found difficult, given her poor hearing, the reticence of patients to speak up, and the other voices in the small, hot tent, creating an insect-like susurrus that was intensified by a definite atmosphere of anxiety: What was wrong with this man, woman or child? Did they have any medication that would help? Could a patient be trusted to take three pills three times daily? Was there an arm sling in the cabinet? Any chemical cold packs? Making things worse, Emmy would insist, despite this not being their "location," on going through her portion of their research protocol just to get the hang of it. Where was the patient born? How long had the patient lived in Harare? How long in this camp? How many relatives lived near by? Did any of them experience the same symptoms? What were the environmental factors that might have caused them?

More than she ever expected, Suzanne enjoyed the camaraderie, the medical sleuthing and debating, the urgent pace, and her reveries about the Vuambas and quandaries about when she would see them again. Going to bed exhausted and waking up in Harare seemed to erase her entire life in the United States. Zimbabwe was like a book from which she had been long diverted but never forgotten: Yes, I know these characters, this place, and these events, she thought. Everything bloomed within her like a long dormant seed, waiting for water and finally receiving it.

She made a sketch of Michelle nose-to-nose with a boy, comically trying to dispel his terror at having a white woman push her fingers into his inguinal canal, probing for a shy testicle. His face was puffy and round, Michelle's was foxy and rectilinear. They were almost kissing through their mutual surprise and laughter. It was innocent but sexy.

She made another sketch, this one of Emmy interviewing a woman, the two of them as far away from each other as they could be, although that only meant five feet.

She remembered art classes when they would do ten sketches in ten minutes, the professor barking at them like a gym instructor to hurry up. "Focus on what matters! Draw what matters! Faster ... faster ..!"

The line outside grew to twenty yards long. Kerry asked Suzanne if she would go out and pre-interview people, filling in the ministry form first. She put on her sunhat, glad to escape from the tent, but some people feared that she was there to cull the line and left before she could send them away. So she told Kerry it wouldn't work -- they had to let people inside before interviewing them. The line reconstituted itself. Before long it had grown to thirty yards.

Over Emmy and Michelle's objections, Kerry changed her mind and asked Robert to take the first cholera patient, a woman, to the address provided by Mrs. Kahiya. Emmy said the woman was too sick to be moved. Kerry said she felt obliged to at least try to do what they had been told. Suzanne could see that running the clinic had begun to wear on Kerry. She was the slowest of the three nurses, so slow that she stopped treating patients herself and fell into the mode of consulting with Michelle and Emmy about the patients they saw, often provoking disagreements and squabbles.

"Kerry, we can help this woman right here with ORS," Emmy said. "She needs hydration, not a cab ride."

"Yes, but what if we can get her to a better place?" Kerry asked.

The woman slumped on the examining table, resting heavily on her left elbow. She was panting; her face was drawn with pain. Emmy said she thought Kerry promised them they were going to use their best medical judgment and not get caught up in a big bureaucracy.

"Especially this bureaucracy -- the one that removed the clinic these people had and can't get us into the countryside! I mean, Mrs. Kahiya, do you think she's a doctor?"

"It doesn't matter whether she's a doctor. Can't you see we're on shaky ground here?"

"No, I can't. I can see sick people on shaky ground, but the ground under us is very solid. She needs treatment here and now."

Kerry had her way, but Robert found no treatment center at the address Mrs. Kahiya provided -- it had been moved or knocked down -- and brought the patient back in worse condition than when she had left. Kerry asked Suzanne to help the woman drink ORS in the tent's rear room.

"She'll live, I think," Kerry whispered to her. "Be sure to wear your gloves."

Suzanne cradled the woman's head and coaxed her to sip slowly. In a few minutes, the ORS seemed to begin taking effect; either that, or the fact that someone was caring for her restored her confidence. Lacking a pillow, Suzanne improvised with an unopened box of surgical gloves. Although it was hotter in the rear room, she enjoyed the relative stillness. She let the woman rest. Then they practiced her holding the bottle of ORS by herself. She would sip from it a little and then hold it upright on her chest and catch her breath. She smelled of diarrhea, of not having bathed or cleaned her teeth. Briefly, Suzanne was aware of Robert in the doorway, looking in on them as he must have looked in on his dying wife. How could he have gone out and driven his taxi leaving her behind? Did he say to himself, "There is no hope?" Did his wife lie to him and tell him she was feeling better? Did he know she was lying? What could he do? He ended up doing this. If it weren't for Sarah and Robert, they wouldn't be here. And this woman, as Kerry had said (how did Kerry know?) would live. Suzanne was astonished; this woman would live.

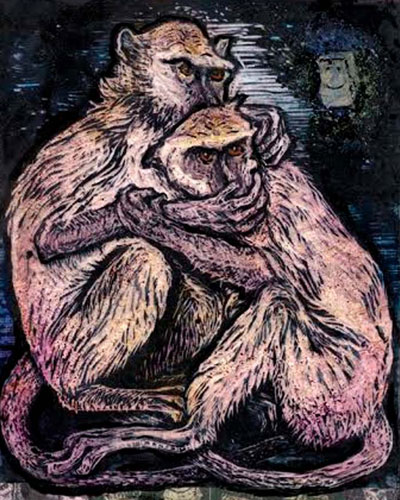

Emmy brought another cholera victim to her. Michelle brought a third. Within a few hours there were four people on the four pallets in the rear room, leaving barely enough space for Suzanne to kneel and twist and bend and help them drink. Bodies on the ground, a landscape of bodies on the ground, she thought, planning to engrave that image. Kerry brought in a bucket of water and a cloth. One by one she washed the patients' soiled bottoms and then fastened adult diapers on them. She was wearing a mask in addition to her gloves and insisted Suzanne put a mask on, too. Suzanne added masks to the bodies on the ground in the landscape of her mind; some she rolled over on their stomachs, the rest she left lying face up, masked, staring at the sky.

"I'm already thinking I'm going to have to become a doctor," Kerry said, "but even a doctor ... It's like the whole world is sick. Who could possibly take care of it?"

Suzanne asked Kerry if she would take over rehydrating people to give her a break. Outside she saw that the line was still ten yards long. How big was this encampment? How many people lived there? Hundreds? Thousands?

Michelle came out of the tent and gave her a bottle of ORS to drink.

"Are you serious?" Suzanne asked. "Do you think I might get it from them?"

"No, but what you might get is real dehydration in that steam box. Look at you. You're sopped."

"So are you." The ORS was heavier than water; it seemed to fold in her mouth. "What time is it?"

"Time to go home."

"Is Kerry ready?"

"Kerry will never be ready."

It took them an hour to get Kerry to agree. At first she wanted them to spend the night. Michelle and Emmy refused; they didn't even fight about it. Just refused. So Kerry spoke to Sarah. All day Sarah had been helping manage the line, bringing people into the tent and sometimes walking them "home" to the low-slung hovels and shipping boxes and makeshift tents where they lived. Along the way she would meet other people who needed care and let them know they now could get it. At one point Suzanne asked her about her background. Sarah said she had been an editor in a small publishing house; now she lived here and wore the same dirty dress every day and the same rubber sandals and never lost track of the cracked, patent leather bag she kept on her shoulder. She had her important papers in that bag, a few photographs, and a little Bible whose pages bloomed out with use like the petals of a wilting flower. But she was not, in Christian terms, a forgiving woman. She wished Mugabe and the government and the soldiers and Mrs. Kahiya ill. She blamed them for this encampment, which she called a valley of dry bones. "They say we are free in this place, that we are not detained. But we have no place to go. Why else would we settle here in these ashes and this dust?" In her gauntness and anger, Sarah was a frightening woman. Her large, mobile, searching eyes bespoke rage. Yet she would do anything Kerry asked. Kerry was the one who had made the clinic happen and Kerry was the one who had the final say, so Kerry now was a Little Boss Sarah was determined to support. She readily agreed, with the help of two of her neighbors, to take charge of caring for the two cholera victims that night who were too weak to be taken back from whence they had come.

As Robert drove them back to the hotel, Suzanne listened to Kerry giving him instructions. Her voice was almost like ORS for the ears. It made Suzanne happy listening to her, so self-assured, so locked-in. Robert was to pick them up at seven the next morning but before that he had to take a note from Kerry to the ICFC warehouse beforehand, which must send them more ORS and diapers and arrange for Robert's car to be filled with petrol and provide some kind of sandwiches or fruits or snacks they could offer people in need. She seemed almost exultant, as if she were the captain of a big ship, or the chairman of a large corporation. The further they drove from the encampment, the more sweetly imperious she became, telling Robert what to say if he had trouble getting the petrol and suggesting he think about starting an ambulance service when the economy in Zimbabwe improved. She almost sounded like Andy, making Suzanne wonder if those were the two who had been meant for each other. Meanwhile Emmy fell asleep and dropped her head on Michelle's shoulder, and Michelle then dropped her own head on top of Emmy's head. Their intermingled hair cushioned things as they bounced along. Suzanne couldn't get out her pad or even her camera, but she sketched them mentally in great detail.

The Piker Press moderates all comments.

Click here for the commenting policy.